Leonid Meteor Shower Peaks This Week: Here's What to Expect

This week, one of the most famous of the annual meteor displays is due to reach its peak: the Leonid meteor shower.

According to Margaret Campbell-Brown and Peter Brown in the 2016 edition of the "Observer's Handbook" by the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, the Leonids should be at their best early Thursday, Nov. 17, at 6 a.m. EST (1100 GMT). This is nearly perfect for those living across much of North America, especially in the central and western regions, where morning twilight will not yet have begun, and where the constellation of Leo (from where these ultrafast streaks of light get their name) is positioned high in the southeast sky.

The meteors appear to streak away from within a pattern of stars that resembles a backward-facing question mark, popularly known as the "Sickle" of Leo. For a single observer, the average hourly rate for the Leonids is typically somewhere between 10 and 20 meteors per hour; rather modest compared to the Perseid meteor shower in August and the Geminids in December. [Leonid Meteor Shower 2016: When, Where & How to See It]

Unfortunately, something else will also be high in the sky that very same morning: a very bright waning gibbous moon, 88 percent illuminated, in the nearby constellation of Gemini. With the moon acting almost like a giant spotlight, lighting up the sky, the number of meteors that might otherwise be seen will be seriously reduced.

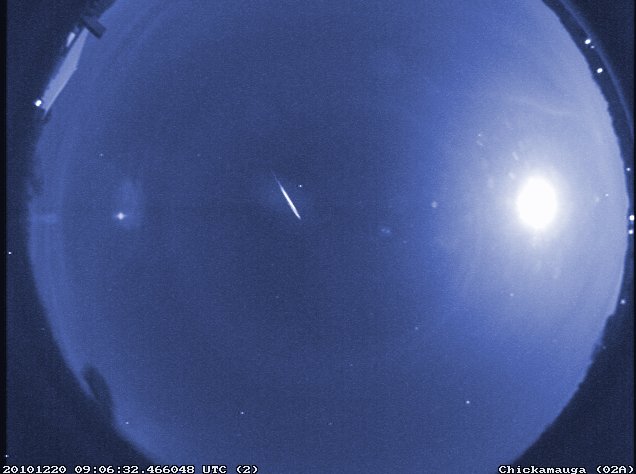

Still, as many as half of the Leonids leave visible trails, and there is always a small chance that a brilliant fireball or bolide (exploding meteor) might appear — one that's bright enough to attract attention even in the bright moonlight.

Stormy times

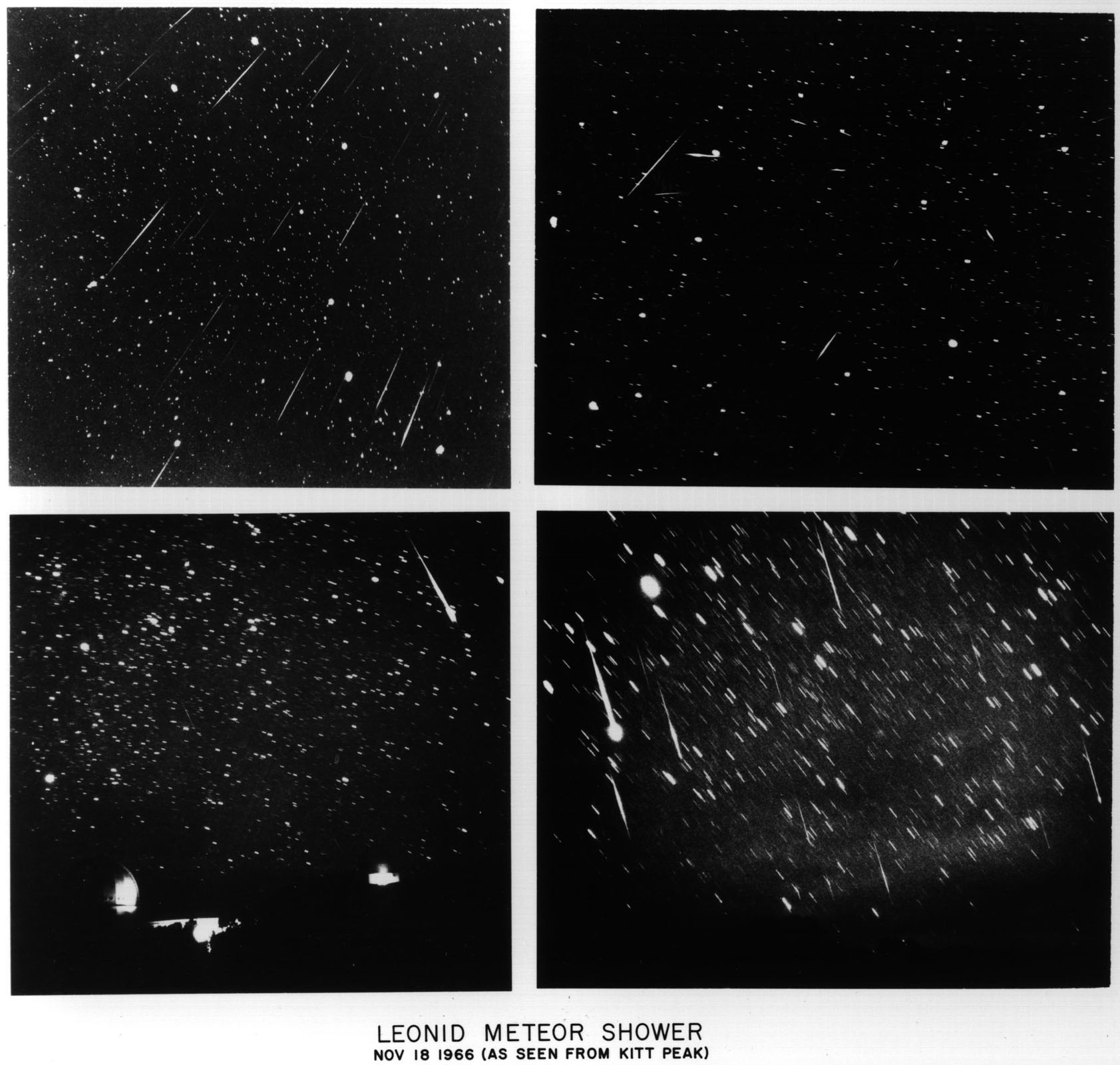

The Leonid meteor shower is an extremely variable shower. A dense swarm of particles consisting of material that is shed by the Comet Tempel-Tuttle returns about every 33 years (the comet’s orbital period), and if it crosses the Earth’s orbit during November, an intense meteor storm is seen. The Leonids produced spectacular displays — exceeding 1,000 meteors per minute —in 1799, 1833, 1866 and 1966 (when observers were left awestruck by the appearance of more than 2,000 per minute). The great swarm that produces these spectacular displays passed through aphelion – its farthest point from the sun, near the orbit of Uranus – last year, and the Leonids have been correspondingly weak in recent years. [Video: The Leonid Meteor Shower & More in November's Night Sky]

The recent lean years have generated only about a dozen or so Leonids per hour, but they are always somewhat unpredictable. The last really bright and spectacular Leonid shower occurred in 2001, when Leonids could be seen at rates of up to 40 per minute. Adding 33 years to 2001, the 2034 Leonids are, naturally, eagerly awaited. More on this later.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Shooting Star Reflections – The Great Storm of 1966

It is difficult for me to accept the fact that this week will also mark the 50th anniversary of the Great Leonid Meteor Storm of 1966. Echoing the title of that memorable song from the 1958 movie, Gigi . . . I remember it well.

It was probably the greatest meteor storm in modern history.

And I missed it!

Like this year, the peak of the 1966 Leonids came early on a Thursday morning.

The weekend before the big sky show of ’66, my grandfather and I visited the Hayden Planetarium in New York, where Dr. Fred C. Hess, an astronomer and powerful orator, urged his audience to be sure to look skyward before sunrise next Thursday morning for – potentially – a spectacular display of "shooting stars." Under the planetarium's domed theater, Dr. Hess told us that given reasonably clear skies, we might see hundreds, or maybe even thousands of meteors per hour.

Then, using Hayden's famous Zeiss star projector, Dr. Hess treated us to a very convincing reenactment of the stupendous 1833 Leonid storm, where in the span of a single night over North America, an estimated 250,000 meteors rained down from the sky.

I couldn't wait for Thursday morning to come.

Sadly, my unbridled excitement turned to a crushing disappointment as the weather that morning failed to cooperate. A weather forecast that had promised no worse than partly cloudy conditions, instead saw clouds covering the predawn sky like a fresh coat of plaster, ruining my view of the Leonids. My grandfather and I could only gaze upward at a charcoal-grey sky that was completely devoid of stars.

At Central Park, at a midnight meteor watch, an estimated 10,000 people were looking at the same cloud cover. I remember saying, "Grandpa, didn't the weatherman on TV say it was going to be only partly cloudy tonight?" To which my grandfather quietly responded with, "I guess the party is over." He then trudged back into the house and went straight to bed. I, on the other hand, stayed up for the rest of the night, hoping for even a small break in the cloud cover — which never came.

Dozens … then hundreds … then thousands!

Beginning around 5 a.m. Eastern Time, Leonid activity began ramping up. Along the Eastern Seaboard, the dawn sky was brightening, but where skies were clear, viewers were able to see Leonids falling at rates of up to 6 per minute before it finally became too bright for people to see the stars. [Most Amazing Leonid Meteor Shower Photos]

Farther west, where it was still dark, Leonids were falling at a rate that was described by many as "too numerous to count." In southern California, one observer commented that he and a colleague: "…watched a rain of meteors, turn into a hail of meteors and finally a storm of meteors, too numerous to count by 3:50 a.m. Pacific Time. Instinctively we sought to shield our upturned faces from imagined celestial debris."

From the 6,850-foot Kitt Peak in southern Arizona, 13 amateur astronomers were trying to guess how many could be seen during a sweep of their heads in 1 second. The consensus of the group was that the peak occurred at 4:54 a.m. Mountain Time, when the staggering rate of 40 per second (144,000 per hour) was reached!

Post mortem, and a look at the future

Today, we know that a dusty trail of debris shed by Comet Tempel-Tuttle back in 1899 was what caused the Super 1966 Leonid Storm. That dusty material had made two revolutions around the sun before colliding head-on with the Earth on that memorable night a half-century ago.

Today, with modern computer technology, astronomers can readily locate the positions of Leonid dust trails from the distant past or far into the future. Indeed, the Leonids will periodically shower our planet in the years to come; in the year 2034, Earth is forecast to move through several clouds of dusty debris that have been shed from the comet from the years 1699, 1767, 1866 and 1932. If we're lucky, we might see Leonids fall at the rate of hundreds per hour, perhaps briefly reaching storm rates of 1,000 per hour.

Unfortunately, on its way in toward the sun, in 2028, a close approach to Jupiter is expected to move Comet Tempel-Tuttle and its densest concentrations of meteoric dust off its current course through space, making it all but impossible — at least through the beginning of the 22nd century — to see a repeat of the Super Leonid Storm of 1966.

Editor's note: If you have an amazing skywatching photo you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a possible story or image gallery, please send your photos to our staff at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.

![Learn why famous meteor showers like the Perseids and Leonids occur every year [See the Full Infographic Here].](https://cdn.mos.cms.futurecdn.net/VDWEKQFLr8yuXkTL4YkHqj.jpg)