All Hab Systems Go at the Mars Desert Research Station

The Mars Society is conducting the ambitious two-phase Mars 160 Twin Desert-Arctic Analogue mission to study how seven crewmembers could live, work and perform science on a true mission to Mars. Mars 160 crewmember Annalea Beattie is chronicling the mission, which will spend 80 days at the Mars Desert Research Station in southern Utah desert before venturing far north to Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station on Devon Island, Canada in summer 2017. Here's her latest dispatch from the mission:

Last week I sent a happy photo home of our crew in the hab.

My daughter Mona emailed me back and told me that she thought that the environment inside the hab looked visually deprived. She followed on with, "Is it like 'The Shining,' Mum, where Jack Nicholson is in the mountains in total isolation with his family and he goes insane and wants to kills everyone with an axe?" [See more Mars 160 photos here, and get daily images by the Mars 160 crew]

Well, Mo, no, it's not really like that here.

But in space, on Mars, where small communities are locked inside together with little visual, tactile and auditory input from the physical world, always in constant threat to life from the harsh environment, devoid of fresh air and natural light and in long, monotonous periods of confined microgravity, a bit like these very long sentences I am writing to you, yep, I can see why you might think that things could get a little crazy.

There's a lot we don't understand about how people will live together on Mars.

When we talk about habitability and long-duration space travel, it's about the relationships between the crew and their environment. No one doubts that the vast scales of space, prolonged stress and sensory and social deprivation can result in maladaptive behaviors and disorders. As we travel far from Earth in our starships to Mars, our lives will need to be regimented, and there will be little room for spontaneity. Every breakdown or mistake can affect the whole crew and put the mission at risk, Within the spaceflight environment, it's difficult to understand the differences between sensory deprivation, social isolation, monotony and confinement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

We are in the final few weeks of phase one of our Mars 160 mission. Our crew of seven have been living at the Mars Desert Research Station for nearly three months, with our eighth crewmember, principal investigator Shannon Rupert, invisible but close by. As I've mentioned previously, this is not an isolation experiment, though we've learned a lot about how we cohabitate. It's true we are secluded and living in very close contact. If I roll over in bed, most people can hear me turn. And unless we are working outside on an EVA (extravehicular activity) in spacesuits, we do always remain indoors in our hab. In the middle of this ancient, beautiful desert, sometimes the Mars Desert Research Station feels like it's the whole world. We're inside all the time, but we are fine. [Gallery: The Most Memorable Spacewalks in History]

This week I've been wondering why. Perhaps part of the reason is that while we recognize each other's needs, we are also very conscious of the needs of the habitat as our shared home. We know that to care for each other, we need to look at where we live and its limited resources. For instance, water is especially precious.

Being able to control one's own environment decreases stress. There's one member of our team who keeps it all ticking over for us — our unshakable, funny and debonair Crew Engineer, Claude-Michel Laroche.

Claude-Michel is a Canadian, born in Montreal. Part of MDRS Crew 143, he has university degrees in both Physics and Physics Engineering. Claude-Michel has always had an interest in space exploration, but after attending the International Space University in Florida in 2012, he decided to become more involved in the space industry. He became a Mars One candidate (Round Two). He then applied to the Mars Society for Crew 365, which eventually led him here, to Mars 160. Now he's keen to work as an engineer or a scientist for the Canadian Space Agency.

So much about life anywhere is routine. Claude-Michel is our dependable, behind-the-scenes person around the hab. This mean he works tirelessly all day on large and small tasks, anything to make the hab more livable, humanizing the interior of our spacecraft by keeping it balanced and working, ensuring we live in comfort. Claude-Michel is the one who can adjust a spacesuit to your back so that it makes you feel as if it's no weight at all. And he can whip up a birthday cake out of chocolate pudding and pancakes in a flash. But his main role here as part of our team is to keep everything in the hab functioning.

Claude-Michel says, "It is very important to understand all the systems in the hab to allow us to play with them and repair them. Systems here need to stay within allowable tolerance, and if one breaks or needs modification, we need to be able to perform the task or design the task to allow the best performance we can. This goes for everything, like the air and the water heater, the spacesuits backpack, the electricity, the computers, the water system and everything else that is required to work and give us the best living time for the whole duration of the mission. As routine tasks go, for an engineer, most of the time it is about extinguishing the fire."

Parallel to his engineering work, Claude-Michel is the key support and principal research collaborator for Heather Hava's Bioregenrative Life Support Systems Project(BLiSS), a mix of human factors studies, life support system and agriculture thatenhances habitability and diet by growing fresh foods.

In fact, we are all research collaborators with Heather. The SmartPots are a hydroponic system that monitors the health of the plants and lets us know whenever they need attention.

Basically, each crewmember has his or her own SmartPot that contains the young plants, a device ("embrace") that is a wearable monitor placed on the wrist and a beacon. Plants are placed in different locations around the hab; some are in the rooms, but most are in the zone where crewmembers spend time. Beacons monitor the physiological data and the movement of the crew near the plants as well as time spent. I have tomatoes, bunching onions and bell peppers. Though the bell peppers are not looking too great, Claude-Michel is pollinating the tomato flowers, and I'm hoping for tomatoes.

Heather's research is funded by a NASA Space Technology Research Fellowship.

She says, ''Plants provide an important link to Earth, exploiting the sensory enrichment of nature in contrast to the stark and sterile machine environment typical of space habitats." And she is right. Inclusion of plants in the hab does positively affect our well-being and enhances the sensory and spatial aspects of the habitat by change through growth. Claude-Michel says it's like nurturing babies. [Plants in Space: Photos by Gardening Astronauts]

We have quite a garden growing here now.

In terms of the computational systems for the initial phases of the SmartPot (SPot) project, Claude-Michel began by configuring all the computers that allow the SPot sensors to stream their readings onto a specific website in order for the data to be compiled. Everything had to be calibrated to allow as much of a precise reading as possible.

Now, on a daily basis, with the help of cross-trained crewmember Yusuke Murakami, Claude-Michel continues to make sure all the readings for the strawberries, spinach, bell peppers, dark purple Mizuna, Tokyo bekana, wonder wok (which is a salad mix), micro-greens rainbow salad mix, Romanian lettuce, dill, coriander, rosemary, basil, spearmint, borage, the tomatoes and the bunching onions are all within specific limits that change daily from SPot to SPot. This means the pH levels of the plants have to be verified as well as the electro-conductivity levels, temperature and dissolved oxygen levels.

Claude-Michel trains and monitors the crew who perform tasks to make sure the plants are growing in the best possible conditions, growing as fast as possible and bearing fruit or edible leaves or roots within mission time frame. So that we can get everything working together in harmony, all our plant tasks are completed by following the protocols provided by the Earth science team who created and engineered the systems.

I won't be leaving our hab until I have tomato salad with bunching onions.

I asked Claude-Michel if he misses the outside world, in particular the smells and the sounds of the physical world, and he says no. He claims he has a very strong sense of adaptation and is hardly affected by sensory deprivation (though he did remember the memory of lemons from the citrus wipes).

When I think about the vastness and the potential bleakness of deep space, for some funny reason, an excerpt comes to my mind from a poem called "Darkness." Written in the early nineteenth century by Scottish poet Lord George Gordon Byron, this excerpt is not even written about space but about darkness, in the "pall of a past world."

But somehow it connects me to an image of leaving Earth and travelling into the unknown:

the world was void

the populous and powerful was a lump

seasonless, herbless, manless, lifeless,

a lump of death, a chaos of hard clay

the rivers, lakes and oceans all stood still

and nothing stirr'd within their silent depths...

Great poem. If only I could remember the rest of it.

From my loft, I gaze up through the open ventilation hole in the ceiling at the very top of the hab. (Claude-Michel tells me in terms of systems, it's the outside point for the air system.)

I can see the dark sky and a chill breeze sweeps in and ruffles my hair.

If it's not already there, when we travel to Mars, we will bring life.

On to Mars.

Annalea Beattie

Editor's Note: To follow The Mars Society's Mars 160 mission and see daily photos and updates, visit the mission's website here: http://mars160.marssociety.org/. You can also follow the mission on Twitter @MDRSUpdates. For information on joining The Mars Society, visit: http://www.marssociety.org/home/join_us/.

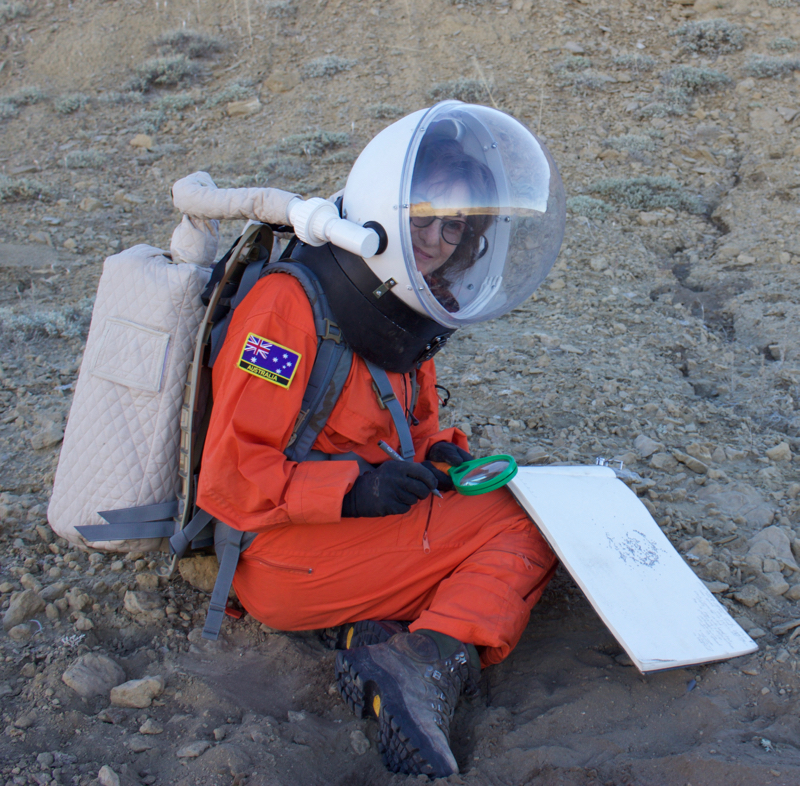

Annalea Beattie is an artist and writer based in Melbourne, Australia, and her art practice is based on space science. She was recently elected a director of the National Space Society of Australia. Annalea is a member of The Mars Society's Mars 160 Twin Desert-Arctic Analogue mission, where her art-based research explores how observation is key to the role of all field geologists, including those on a planetary exploration crew. Follow The Mars Society on Twitter at @TheMarsSociety and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.