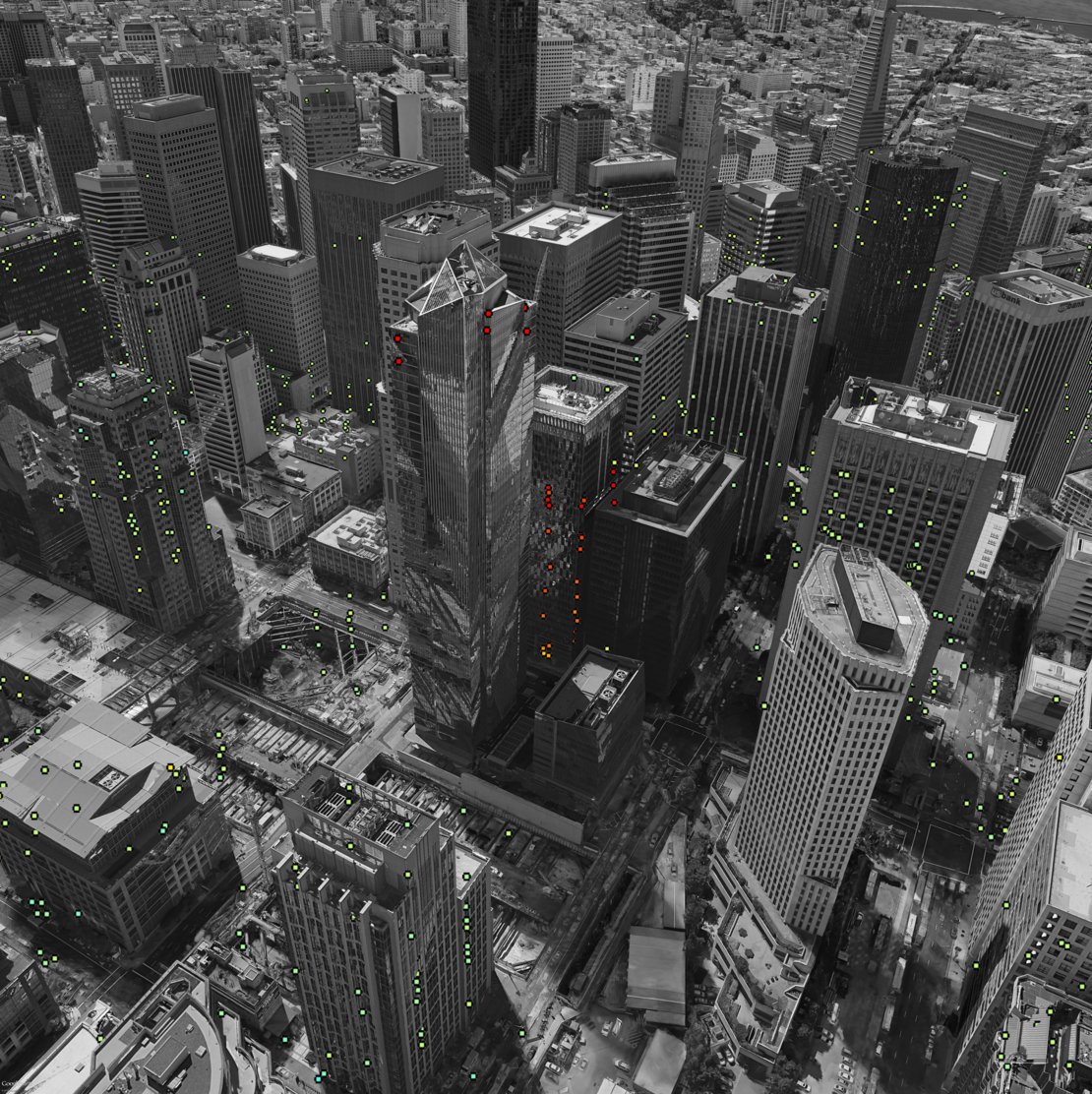

San Francisco Skyscraper Is Sinking, Satellite Images Show

San Francisco's Millennium Tower skyscraper is subtly sinking by a few centimeters a year, according to measurements taken from the European Space Agency's (ESA) twin Copernicus Sentinel-1 satellites.

The 58-story Millennium Tower — also called the leaning tower of San Francisco — opened its doors in 2009, and has recently shown signs of sinking and tilting. In fact, the satellite imagery (released on Nov. 25) indicates that the skyscraper has sunk nearly 1.9 inches (50 millimeters) over a one-year period. This data has broad implications for helping scientists to study similar land subsidence that has been observed in Europe, ESA officials said in a statement.

While researchers have not yet determined why the Millennium Tower is sinking, "it is believed that the movements are connected to the supporting piles [foundation] not firmly resting on bedrock," ESA officials said. [Photos: Amazing Images of Earth from Space]

In order to detect the subtle surface changes that have been observed in San Francisco, scientists used multiple radar scans from the twin satellites — a technique that works well with the city's skyscrapers, as the buildings "better reflect the radar beam," officials said.

Using this method, scientists have been able to map subsidence, or sinking, hotspots across the wider San Francisco Bay Area — including areas along the earthquake-prone Hayward Fault — as well as areas of uplift around the city of Pleasanton, which is likely due to the replenishment of groundwater, following a four-year drought that ended in 2015. Scientists plan to use the satellite imagery that has been taken of San Francisco to learn more about land subsidence in other areas around the world. For example, severe subsidence has been observed in Oslo, Norway.

Much like the sinking of the Millennium Tower, the subsidence in Norway is believed to be linked to the buildings' structural integrity. For example, newer buildings, such as the opera house in Oslo, have a proper foundation that was built into bedrock, while subsidence has been observed in older areas around the city's train station without such a foundation.

"Experience and knowledge gained within the ESA's Scientific Exploitation of Operational Missions program give us strong confidence that Sentinel-1 will be a highly versatile and reliable platform for operational deformation monitoring in Norway, and worldwide," John Dehls, from the Geological Survey of Norway, said in the statement from ESA.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

What's more, the use of the twin Sentinel-1 satellites provides a "cost-efficient" method for studying ground movement, compared to localized case studies. In addition to monitoring land subsidence, the two Earth-observing satellites can also be used to map Arctic sea ice, survey forested environments and more.

Follow Samantha Mathewson @Sam_Ashley13. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.