Here's How NASA's Hurricane Satellite Fleet Will Work

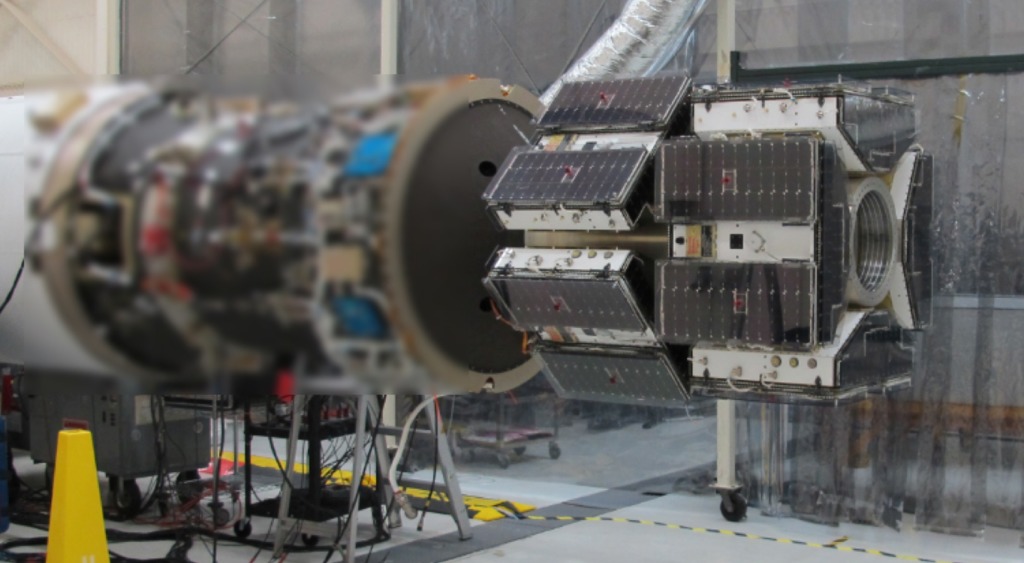

Eight specialized microsatellites, slightly larger than carry-on suitcases, will launch from beneath an airplane Dec. 12 to begin monitoring hurricanes and cyclones in the tropics, piercing through rainfall to measure wind speeds at a storm's heart.

Previous satellites have measured wind speed over water by shooting radio waves at the ocean and measuring how the waves scatter on the surface, indicating the wind speed. But such satellites could only monitor one site at a time, and the radio waves could be scattered when rainfall was too heavy, like deep within a hurricane.

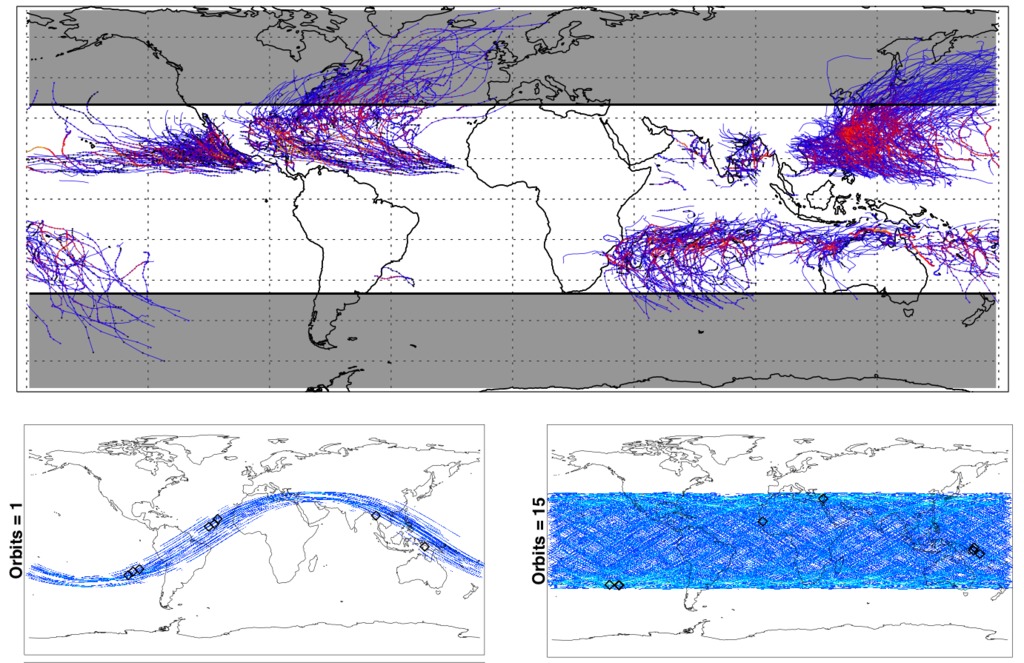

The constellation of satellites in CYGNSS — the Cyclone Global Navigation Satellite System — lighten the load by only carrying receivers, and instead picking up reflected GPS signals already sent down to Earth by navigation satellites. Those microwave wavelengths can penetrate through the hurricane to measure its wind speed, researchers have said — and working together the eight satellites can survey the hurricane danger zones much more thoroughly, reporting back to ground stations in Hawaii, Chile and Australia. [NASA's CYGNSS Hurricane-Tracking Satellites in Pictures]

"This will be the first time ever that satellites can peer into hurricanes and predict how strong they'll be when they make landfall," Chris Ruf, CYGNSS' principal investigator and researcher at University of Michigan, said in a video.

The CYGNSS satellites are scheduled to be air-launched by an Orbital ATK Pegasus XL rocket at 8:19 a.m. EST (1319 GMT) on Monday. The rocket will be flown to launch altitude by its L-1011 Stargazer carrier craft, which will take off from NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Cape Canaveral, Florida. You can watch the entire CYGNSS launch webcast online here, courtesy of NASA TV, beginning at 6:45 a.m. EST (1145 GMT). NASA will also hold two webcasts Saturday, Dec. 12, to preview the mission.

Each of the little satellites will collect those reflected GPS signals to measure the wind speed every 90 minutes from four spots on the ocean surface simultaneously as they orbit through the tropics. Unlike monitoring a hurricane with a single satellite, which can only measure a given location again after a lot of travel time, a trouble spot measured by one CYGNSS satellite will be passed over by another satellite within seven hours, Ruf said during a news conference in November.

At eight satellites making four measurements each, it's like having 32 virtual airplanes flying around making measurements simultaneously, he said. (Airplane-carried hurricane monitoring devices do currently exist, but according to Ruff their technology can't be scaled to space.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Because of the CYGNSS fleet's small size and lighter load, the whole ensemble cost just $162 million to build and operate. By measuring hurricanes as they grow and change, researchers will learn a lot about hurricane evolution — and judge the danger of approaching hurricanes in real time.

"In the vast majority of cases, we can predict track very accurately; we still have a very hard time knowing how intense the storms will be when they get where they're going," Derek Posselt, CYGNSS' deputy principal investigator, also from the University of Michigan, said in a video. Hurricanes' intensity, and wind speed in particular, "determines how much damage there will be, and it determines whether or not you're going to need to evacuate the population or whether they can shelter in place."

"When you're talking about impact of hurricanes, the intensity is pretty much 90 percent of the story," he added.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.