Notes from Mars 160: The Space Architecture of Yusuke Murakami

The Mars Society is conducting the ambitious two-phase Mars 160 Twin Desert-Arctic Analogue mission to study how seven crewmembers could live, work and perform science on a true mission to Mars. Mars 160 crewmember Annalea Beattie is chronicling the mission, which will spend 80 days at the Mars Desert Research Station in the southern Utah desert before venturing far north to Flashline Mars Arctic Research Station on Devon Island, Canada in summer 2017. Here's her latest dispatch from the mission:

Hello, all.

The study of "extremophiles" provides us with clues about possible forms of extraterrestrial life and where to look for such life. Extremophiles are organisms that survive at the limits of life in extreme physical or geochemical conditions.

The word combines the Latin extremus, meaning "extreme," and the Greek philiā (φιλία), which means "love." [See more Mars 160 photos here, and get daily images by the Mars 160 crew]

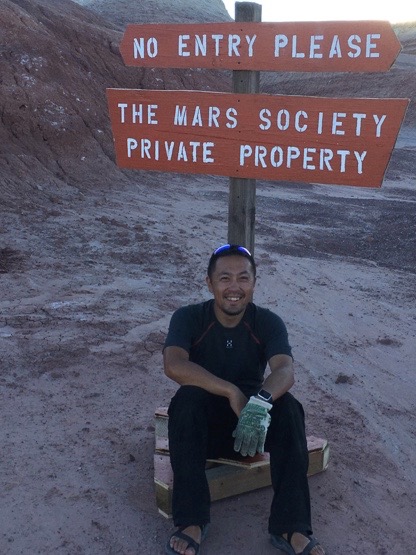

On our Mars 160 crew, if any of us could be thought of as an "extremophile," in the sense of having an extreme love of life and the ability to adapt and survive in harsh environments at the limits of life, Japanese architect Yusuke Murakami is the person.

Yusuke has had more experience of extreme environments here on Earth than the rest of us on the Mars 160 crew put together. He was a member of the 50th Japanese Antarctic Research Expedition and has spent time in by far the coldest, highest and windiest continent and the harshest environment on our planet. Antarctica is below freezing most of the year, has little rainfall and is subject to katabatic winds, long periods of sunlight and long periods of darkness. In Antarctica, Yusuke was part of a 28-person Wintering Crew. His role was mission specialist in mainly geophysics, a member of a team who works to understand the physical properties of the Earth from a window on the planet, the Antarctic continent.

As Executive Officer (XO) for Mars 160, Yusuke's role is to support the Commander, ensuring Alex's directives are followed.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Yusuke also has the complex task of understanding the food inventory for the hab. In collaboration with Earth-based experts, overall he assists in measuring how much food we need in total for 80 days. In this first phase of the mission, he also monitored what was needed for 20 days at a time. In the Arctic, we will be just stocked once for food for the whole three months, so it's important we think about our requirements and get the balance right.

Yusuke is also cross-trained by Claude-Michel in caring for plants as a research collaborator for Heather Hava's NASA-funded Bioregenerative Life Support Systems Project(BLiSS), a mix of human-factors studies, life support system and agriculture. This study enhances habitability and diet by growing fresh foods. In the Arctic, Yusuke will take over Claude-Michel's role as principal operator and will set up the systems and monitor the crew as they care for their individual smartpots. [Plants in Space: Photos by Gardening Astronauts]

As well as all these responsibilities, Yusuke is a valuable member of our science team and is cross-trained in lichens, as a science generalist both in the field and in the lab.

Yusuke is a magician with technology and one of our best cooks. His signature creation for Mars 160 is very special — he calls it spam sushi.

I asked Yusuke how an understanding of Antarctic conditions helps us to think about extremity, especially on places like Mars that are subject to combined stresses that preclude most of life.

Yusuke says that, although we have an understanding of the Martian environment from a distance, extremity is still basically an unknown condition. No one really knows how the ambiguity of deep space, extreme distance and isolation will impact humans living off-Earth. Disconnected from our planet, living in small groups under surveillance and being confined in poisonous environments could increase ennui and lassitude, as a major issue for human factors in extraterrestrial settlement. Here on Earth, Yusuke believes extremity is an expression relative to experience. Humans define limits over time, and our limits change as we adapt.

For this mission, Yusuke's key research combines architecture and science operations. The Dome Project compares working processes in and out of spacesuits.

The Dome Project began several years ago, and year by year it has changed its purpose.

Originally it started in the classroom as a children's project. But in 2014, after the big earthquakes in Nepal, Yusuke decided to adapt his research to see if he could help his friends in need overseas. (Previously he had spent some time in Mt. Everest Base Camp as part of an engineering crew for mountaineering teams).

After 10 days of consecutive earthquakes, Yusuke packed up his dome prototype and travelled to Nepal to see if the dome could be useful as a shelter. It was a functional emergency shelter but needed to be modified. Yusuke's great experiences working with children and his time with the Nepali people give him inspiration and hints for further developing the dome design. He returned to Japan to source the human resources needed to hand-make the unit parts of domes as earthquake shelters.

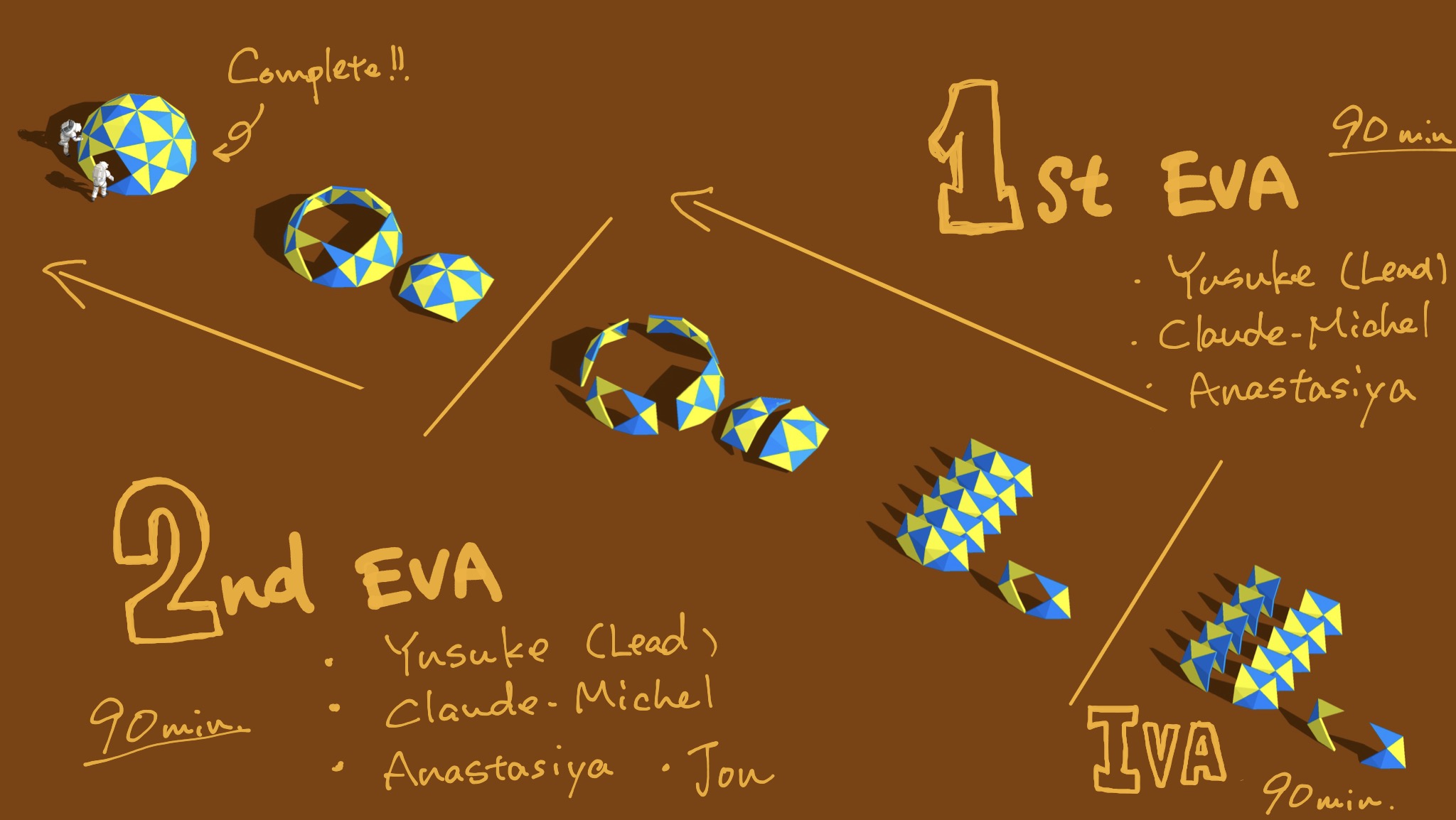

Outside our hab, in very chilly conditions, Yusuke and a team of four from our crew have just finished assembling the yellow-and-blue dome, which consists of approximately 46 units.

Initially, the first stage of construction took place indoors, connecting basic parts.

Moving the dome outdoors required the team to pressurize and de-pressurize in the airlock with the dome units. Yusuke determined that four components together are the standard measure of human scale, as this size is the size of the airlock, the exit and entry to our hab. With 12 joined sections ready to go, the team moved outside.

Over the next two days, a team of first two, then three astronauts in spacesuits began to assemble the dome. [Spacesuit Suite: Evolution of Cosmic Clothes (Infographic)]

I asked Yusuke about the purpose of working on the dome project here, and he answered that it's about a measure of activity: "In Japan, the tatami mat is a measure of human-sized physical space in the house. We can say that how people worked to assemble the dome is a measure of human-sized process, as a kind of a space tatami, a module for the future, as a baseline for designing a Mars station in space."

What was learned is that wearing spacesuits makes crews assemble technology in a similar way. The spacesuit homogenizes (makes the same). Measuring these methods of assembly helps us to understand how people work together as a team and clearly identifies transparent human-centered outcomes in terms of process — useful knowledge that will inform Yusuke's next architectural work.

Yusuke says, "Usually architects who want to design space stations are always thinking about form. Nobody cares about how people can work in space conditions.

"Human-centered design never comes from the inspiration of just one designer but from the knowledge and experience of everyone involved. Before I can design space architecture, I want to understand how people work in spacesuits, building a team together, as a kind of living, human-centered design. The dome module connects many people, architects, astronauts, Earthlings. My interest is human."

There's a saying Yusuke likes that says, "if you want to go faster, go alone, but if you want to go farther, go together." The name of Yusuke's dome is Dare Demo Dome, which means "a dome for everybody" in Japanese.

To envisage a new kind of future, all kinds of different people will be needed to go to Mars. Beyond frameworks of need and deficiency, imaginative people like Yusuke Murakami will be included in early extraterrestrial societies to build rich cultural practices and highlight possibilities for social cohesion, connection and agency.

For me, Yusuke's architecture is much more interesting than a focus on formal and aesthetic concerns, as it involves measuring the limits of human experience.

Good art — in this case, good architecture — promotes collective and individual development and invents common languages that alter perceptions and encourage us to imagine different alternatives for life.

All rationales for space activities are cultural rationales. (As stated in Dator J. 2012, Social Foundations of Human Space Exploration, Springer Publications: Switzerland.)

MARS OR BUST.

Annalea Beattie

Editor's Note: To follow The Mars Society's Mars 160 mission and see daily photos and updates, visit the mission's website here: http://mars160.marssociety.org/. You can also follow the mission on Twitter @MDRSUpdates. For information on joining The Mars Society, visit: http://www.marssociety.org/home/join_us/.

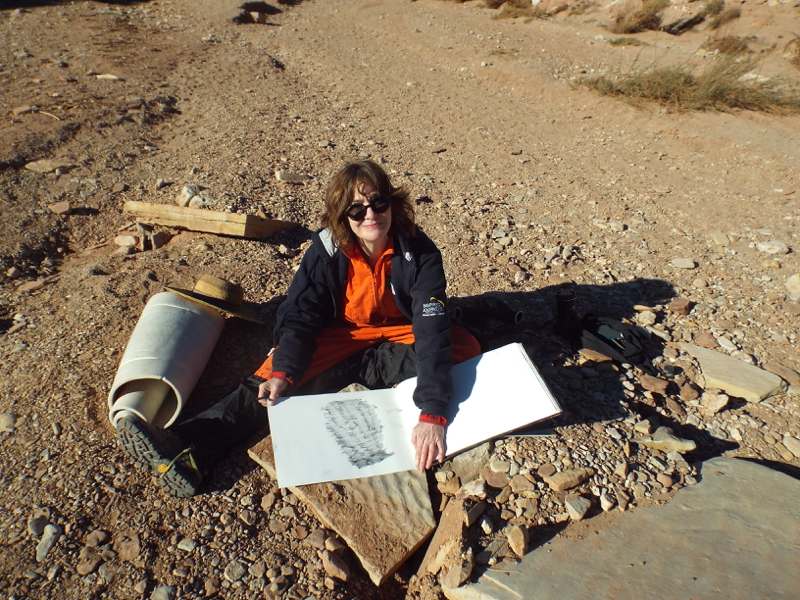

Annalea Beattie is an artist and writer based in Melbourne, Australia, and her art practice is based on space science. She was recently elected a director of the National Space Society of Australia. Annalea is a member of The Mars Society's Mars 160 Twin Desert-Arctic Analogue mission, where her art-based research explores how observation is key to the role of all field geologists, including those on a planetary exploration crew. Follow The Mars Society on Twitter at @TheMarsSociety and on Facebook. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.