Extinction-Level Superflares May Blast Earth's Nearest Exoplanet Proxima b

The recent discovery of a planet around the star closest to Earth's sun has raised hopes that life might exist around the sun's nearest neighbor, but researchers now find that this world might frequently experience extinction-level "superflares" from its star.

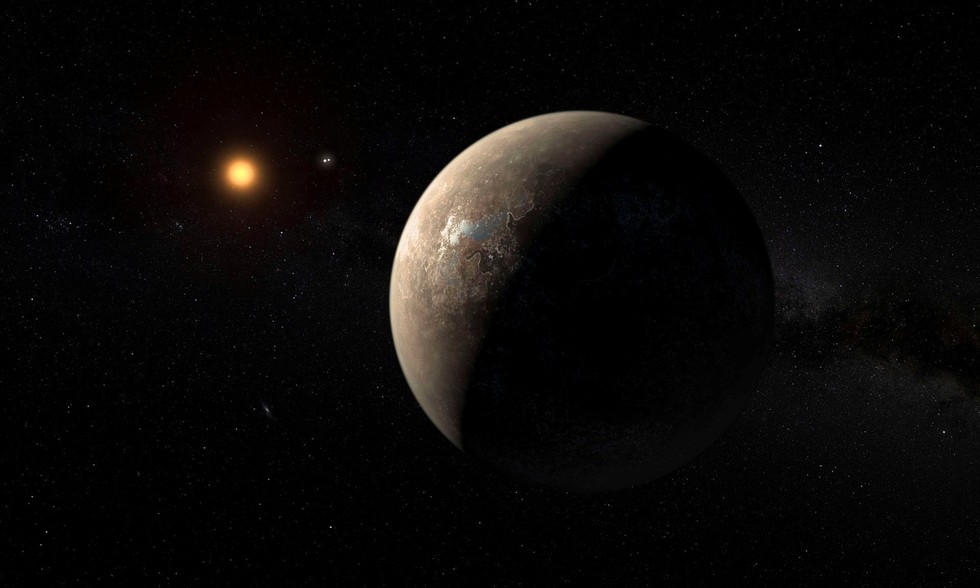

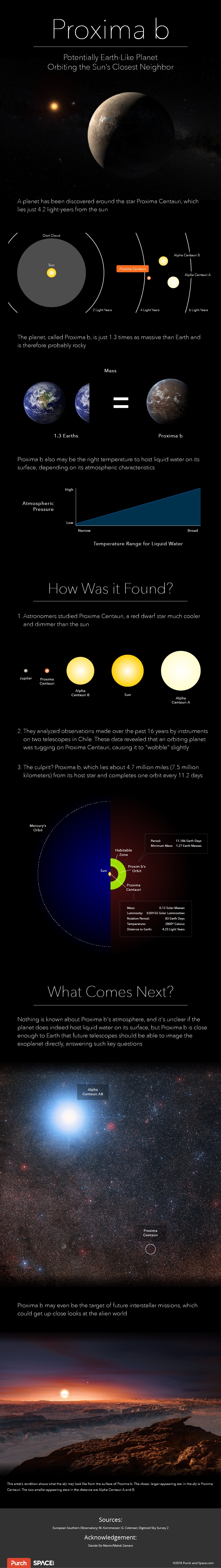

In August, scientists revealed the existence of an alien world around Proxima Centauri, a red dwarf star more than 600 times dimmer than the sun that lies just 4.2 light-years from Earth's solar system. This exoplanet, known as Proxima b, could be rocky and about the size of Earth. It also lies in its star's "habitable zone," the area around the star warm enough for the planet to potentially host liquid water on its surface. Since there is life virtually wherever there is water on Earth, being positioned in the habitable zone would raise the chance that Proxima b is home to life as it is known on Earth.

However, life likely needs more than just warmth and water to survive. Past research has found that many exoplanets are subject to superflares from their host stars, which can be up to thousands of times more powerful than ones seen so far from the sun. These massive flares could scour life from planets, especially those close to their stars, like Proxima b, which orbits Proxima Centauri at a distance one-tenth that between Mercury and the sun. [Proxima b: Closest Earth-Like Planet Discovery in Pictures]

To find out what effects flares might have on exoplanets, study author Dimitra Atri, a research scientist at the Blue Marble Space Institute of Science in Seattle, ran computer simulations modeling the interactions of planetary atmospheres with protons released during flares. These simulations included a wide range of flare strengths, planetary atmospheric thicknesses, orbital distances from stars and planetary magnetic field strengths, all factors that can influence how much radiation the surface of an exoplanet might receive.

Atri found that if Proxima b had an atmosphere and magnetic field like Earth's, superflares would not have any significant effect on the planet's biosphere. However, if Proxima b's atmosphere is slightly thinner, or its magnetic field is much weaker, the alien world would likely receive "extinction-level" doses of radiation from superflares, Atri discovered.

"I would say that it is too premature to call Proxima b habitable," Atri told Space.com. "There are many factors that would decide whether such a planet can sustain a biosphere. More data will help clarify the situation."

Prior work found that red dwarf stars such as Proxima Centauri, also known as M stars, constitute up to 70 percent of the stars in the cosmos, making them potentially key places to search for life. Because M stars are dim, the habitable zones of red dwarfs lie near these cold stars, often closer than the distance of Mercury from the sun. These findings suggest that superflares might pose a major threat to life on worlds in red dwarf habitable zones.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Here is how I think about this — the weather in Fukushima [Japan] right now is in the mid-50s [Fahrenheit, or about 13 degrees Celsius], a bit chilly but a good temperature to spend time there," Atri said, referring to the site of a nuclear power plant disaster in 2011. "However the radiation dose there is too high, which would make living there too risky. The same is true with 'habitable' planets around M stars. They might have an optimum temperature, but stellar flares would produce very high radiation doses at regular intervals.

"One important aspect of this work is highlighting the critical importance of having a significant planetary magnetic field and good atmospheric shielding," Atri said. "With these two factors, even the most extreme stellar flares will not have much impact on a primitive biosphere."

Atri did note that previous research has found that some microbes on Earth can withstand very high doses of radiation, and that life on other worlds might also be radiation-resistant. "I am working with some experimentalists to reproduce such high radiation doses in a lab and see how different microbes respond," Atri said. "I think that would tell us a lot about potential life on planets such as Proxima b."

The new research appeared online on Sept. 30 in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us