Interview: Inside Astronaut Don Pettit's Jaw-Dropping Space Photography

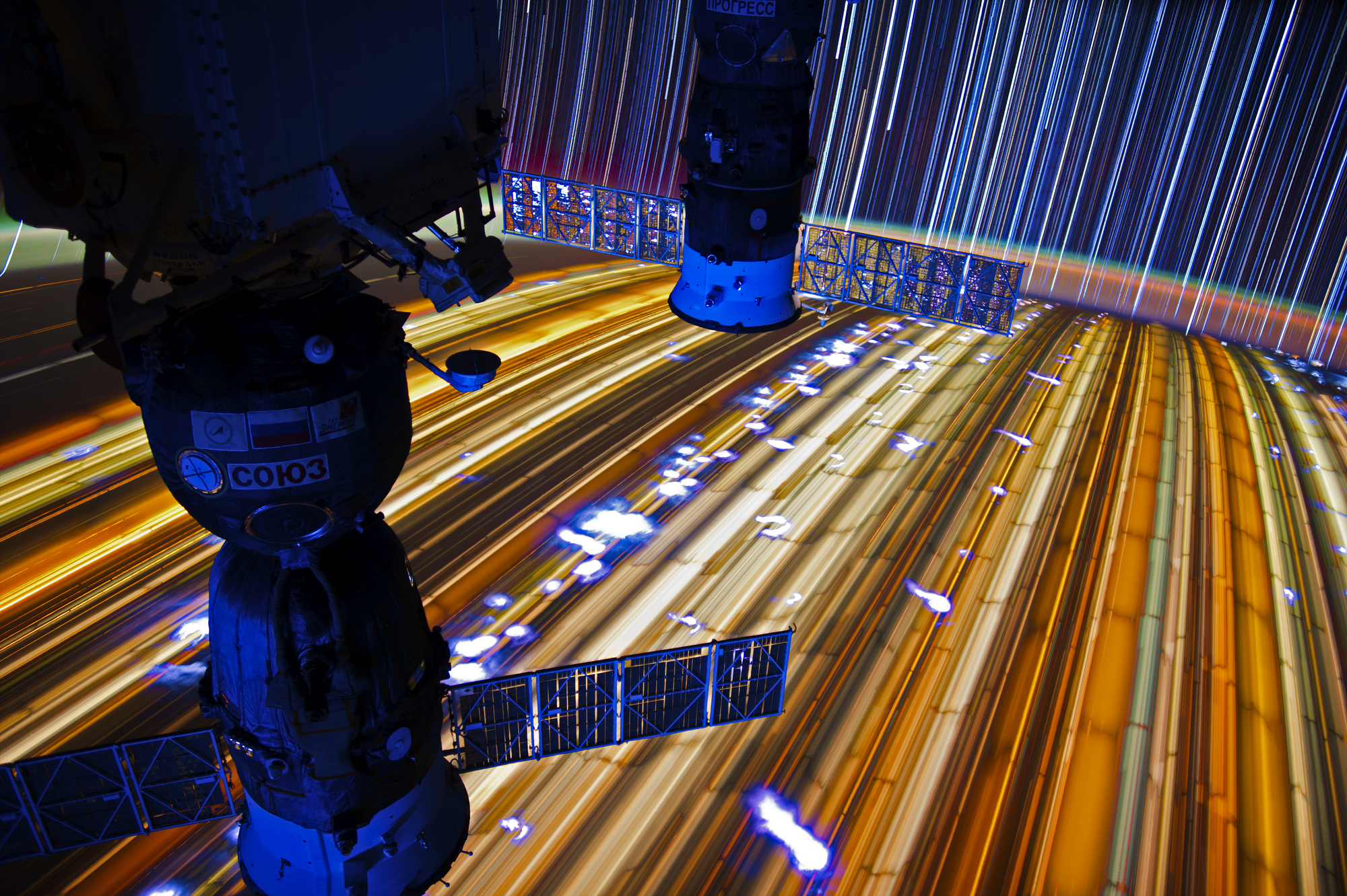

NASA astronaut Don Pettit has flown in space three times, two of them long-duration stays on the International Space Station, and he made the most of his extended time in space capturing hundreds of thousands of photographs of what astronauts see from space — beautiful photos of Earth's cities at night and airglow, the circling of star trails in space over time and the station itself.

The best of Pettit's photographs are collected in a new coffee-table book, "Spaceborne" (Press Syndication Group, 2016), which vividly spotlights the extraordinary sites visible from an orbital perspective. (Space.com readers can get 15 percent off on the book using the code "psg15" on the book's website.)

Space.com talked with Pettit about the very first photo he took, rigging up a device to capture nighttime cities from space and the strange Earth phenomena one can only see from above. [Don Pettit's Amazing "Spaceborne" Photos (Gallery)]

Space.com: Can you tell me about the first photos you took from space, and what that experience was like?

Don Pettit: Oh, gosh. I think the first photos I took from space were of the [space shuttle's] external tank; it was on a shuttle flight, and I was one of the new guys, and that's one of the things they put the new people doing … Right after the main engine cutoff, or MECO, you take photographs of the external tank that you've just punched off of, and the purpose of the photos is for an engineering analysis of the external tank — what shape it was in, whether the foam was lost. These are engineering photos; these are not photos that are supposed to be pretty or artistic.

The big thing to do right after the first few seconds of being in space is to get these cameras out and make sure you've got the subject in field of view and focused.

Space.com: All while grappling with being in microgravity for the first time.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Pettit: Right. You have stomach awareness, you don't know how to move around, you're still in your spacesuit, you're kind of clunky, and it's a pretty daunting task for a newbie. Usually — I think they had me running a video camera, because using the still camera with a 400 mm lens is a completely different skillset.

Space.com: What were your first more aesthetic photos, then?

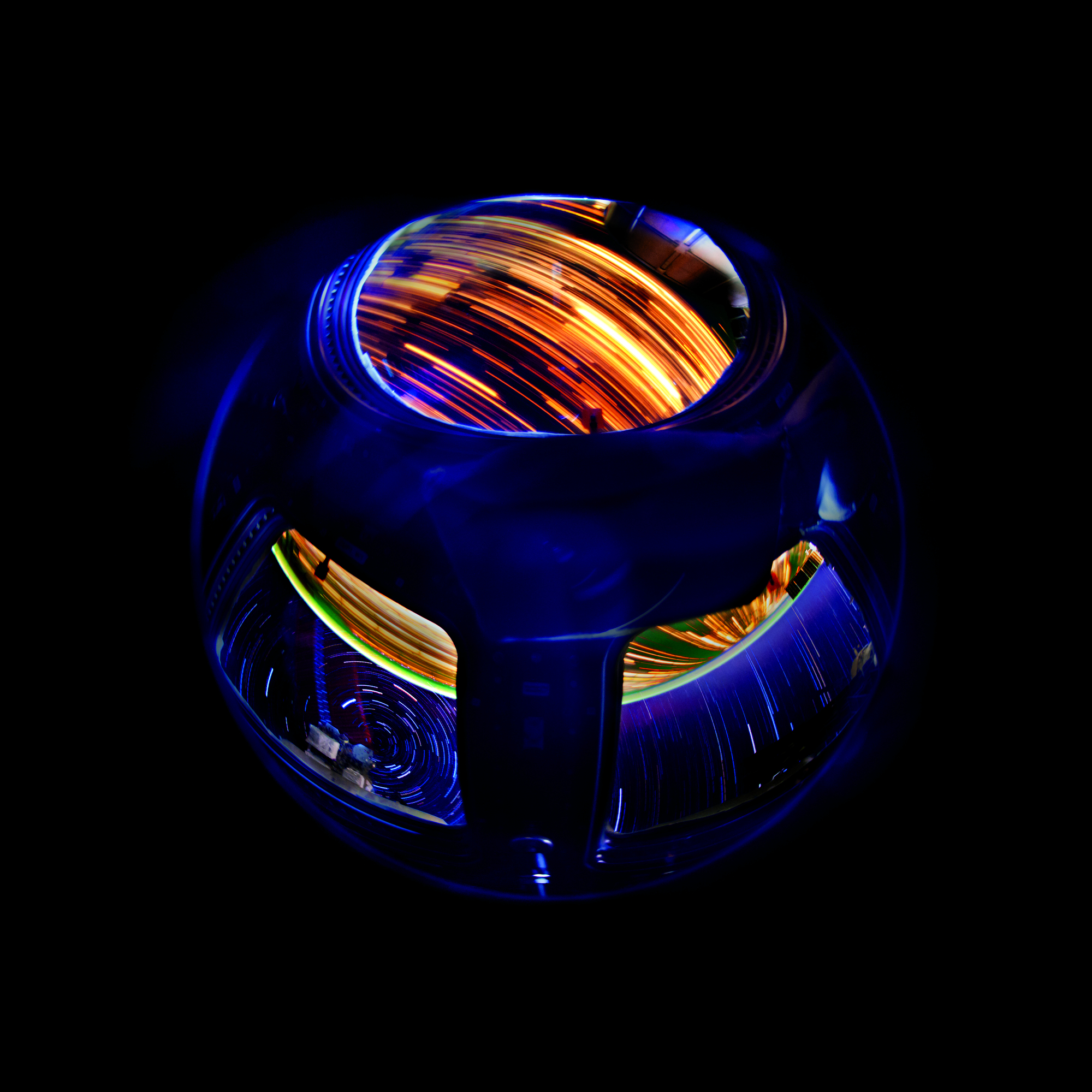

Pettit: One of the first things that I really tried to do was to capture what cities at night look like. With your eyes, you look down at the cities at night and you could see all kinds of detail — and even though they represent a source of light pollution, they're still a beautiful display of something about what humanity is doing to the Earth. With the current digital cameras [at the time] and with film, we just weren't able to capture what the cities looked like — they'd be blurry streaks and unsharp fuzzy images … it was primarily because the exposures were about a second, and the orbital motion would make the cities blurry, so you were stuck.

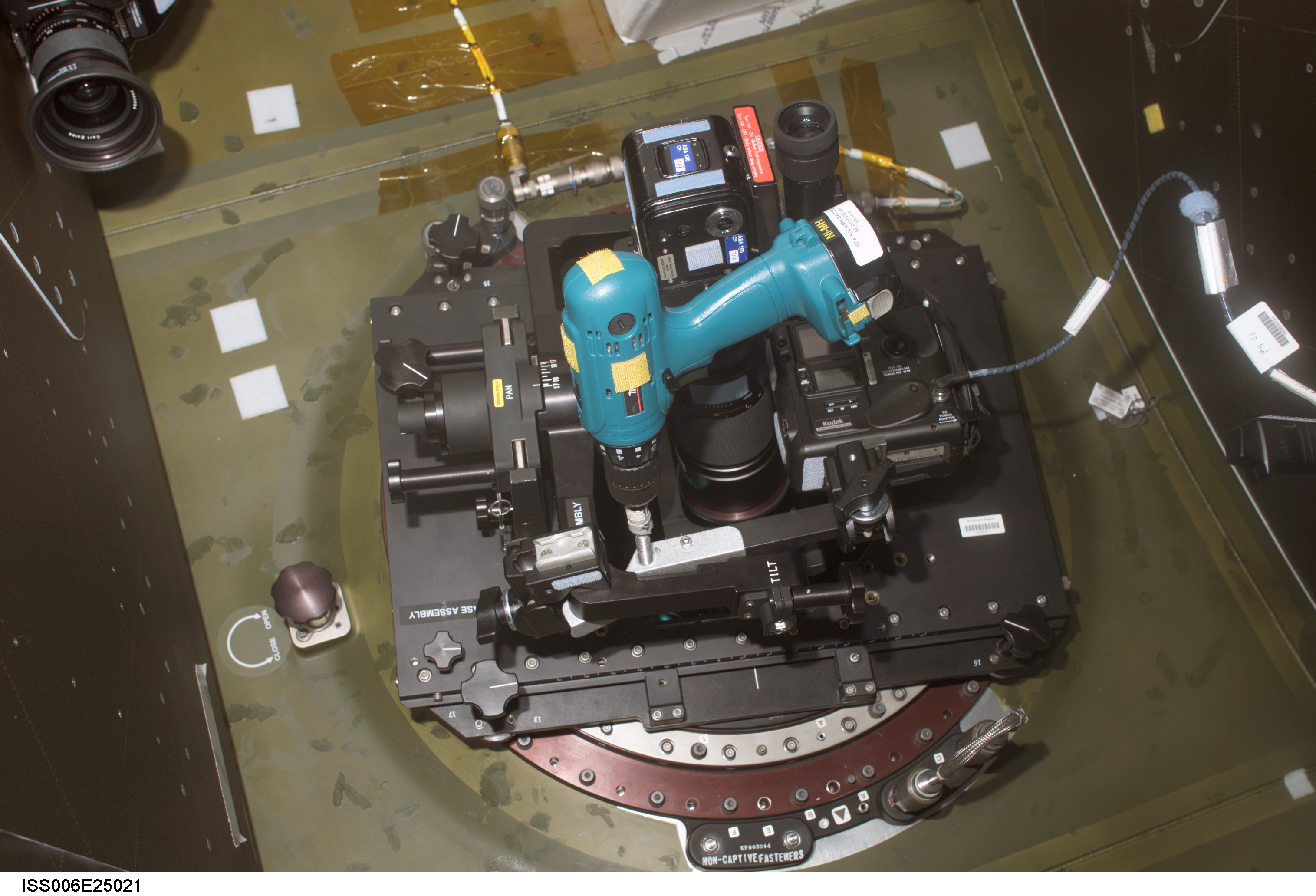

What I was able to do was get a little tilting platform and move it real smoothly by turning a screw with a drill driver, and then I had a telescope mounted to the platform; I'd look through the telescope and turn the screw at a rate that would make the image of the city stationary, and then I'd take a picture with the real camera that I had also mounted to the platform. This would allow me to get three or four pictures off before I had to back up the screw to its initial position.

The whole apparatus [is called] a barn-door tracker. Amateur astronomers — I consider myself one — will use this on Earth to counteract Earth's rotation to take pictures of space, and so I was using the same concept in space to counteract orbital motion to take pictures of Earth.

Space.com: Do people still use it in space?

Pettit:Nowadays the camera technology has advanced; the ISOs are so much faster that we don't need the barn-door tracker. The one I cobbled up was torched on a cargo vehicle that burned up in the atmosphere, and we can smoothly track manually by hand and get really sharp pictures of cities at night now with our modern cameras. [Best Space Photography books]

Space.com: Any other phenomena from space that you were eager to capture?

Pettit: Atmospheric airglow [is a] fascinating phenomenon that you could see from orbit, not so much with your eyes, but after you take a time exposure you could see the glow — the whole atmosphere at nighttime glows from solar particles hitting the atmosphere. It glows at a number of different wavelengths … sometimes you see this reddish glow and sometimes you see it green, and sometimes it's a little mix between them and it'll have a yellowish tint to it.

This is different than aurora; this is just a continuous glow in the atmosphere, and scientists have known about it for about 100 years. You can measure it with sensitive instruments on the ground, but to actually get a picture of it takes an orbital perspective looking obliquely through the atmosphere so you have a long path length.

It kind of looks like a slice of key lime pie that's wedged on top of the Earth — this shows up in a number of my pictures. There's artistic value to all of this, as well as scientific value. I think that's one of the neat things, particularly with my nighttime photos: there's a lot of natural phenomena visible in the photos, and you could talk about that for tens of minutes, but at the same time you can view it as an artistic rendition of something that involves Earth. Definitely an intersection of art and science.

Space.com: What do you hope to show people through your photos of space?

Pettit: What can be seen from orbit. When you document an expedition or a vacation or someplace like the mountains or the bottom of the ocean, you try to show what the environment is like. There's the natural environment in which you're immersed, when you're in space, and then there is the environment in your spaceship that allows you to be there. And that environment is radically different from what most people on Earth are used to seeing. It's kind of like halfway between a submarine and an airplane; you've got a lot of strange pieces of equipment that are required to keep you alive and allow your vehicle to move in space, and showing those kinds of photographs along with the natural photographs of the Earth-space environment, I think, helps show what it is like when you go into space. It's kind of like an Antarctic explorer having a picture inside his tent as well as pictures of the trans-Antarctic mountains. [Watch: Spectacular Video Captures Views of Star Trails from Space]

Space.com: If you could go anywhere in the solar system and explore, where would it be?

Pettit: Since I've already spent a lot of time going in circles around Earth, I'd love to go someplace where I haven't been. I'd probably venture far enough away to go to [Jupiter's moon] Europaor [Saturn's moons] Enceladus or Titan, or some of those far-out places. I bet you could get some amazing photographs of the Saturn rings reflecting different sun angles off of the rings while you'd be on a [moon] that was in orbit around Saturn.

We've captured a lot of that with satellites; think of them as robots that we send to these places and they've made some amazing photographs. I think if you had a human behind a camera in the same environment, you would get a different kind of photograph. A human being will see something and decide, perhaps from an irrational urge from within, that "Wow, that's neat, let's take a picture." A satellite can't do that; a satellite can be preprogrammed to take pictures.

And — I want to put in a plug for the satellites. Once you figure out what you want a picture taken of, human beings are really good at making a machine, a satellite, to take those pictures, and a satellite can generally take more pictures that have higher resolution than what a human being would be able to do. There's a time and place for both.

Space.com: When you first started taking photos of Earth you used film, and then digital cameras, but they'd only be available to the public much later. What do you think of astronauts posting photos through social media?

Pettit:I think it's just fabulous that an astronaut can take some pictures and share them with anybody that wants to sign up, and do that rather quickly. You don't have to go to the NASA archives and dig the photos out, they just come to your cellphone. I think that's really neat. And the quality of the pictures that come to your cellphone, they've been dumbed down a lot, but they're a good-enough quality and it can give you an idea of what the environment is like and what the astronauts are seeing or doing. It's a different venue to share what this experience is like.

That's something that you find: Explorers through the ages have always tried to share the experience. You look at after photography was developed, and you look at the Antarctic and the Arctic explorers from the early 19[00]s … they told stories and they shared the experience with everyone that didn't have a chance to gointo the Arctic or the Antarctic. That's the same with a space venue.

This interview has been edited for length.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.