SAN FRANCISCO — Life has left its mark just about everywhere on this verdant planet.

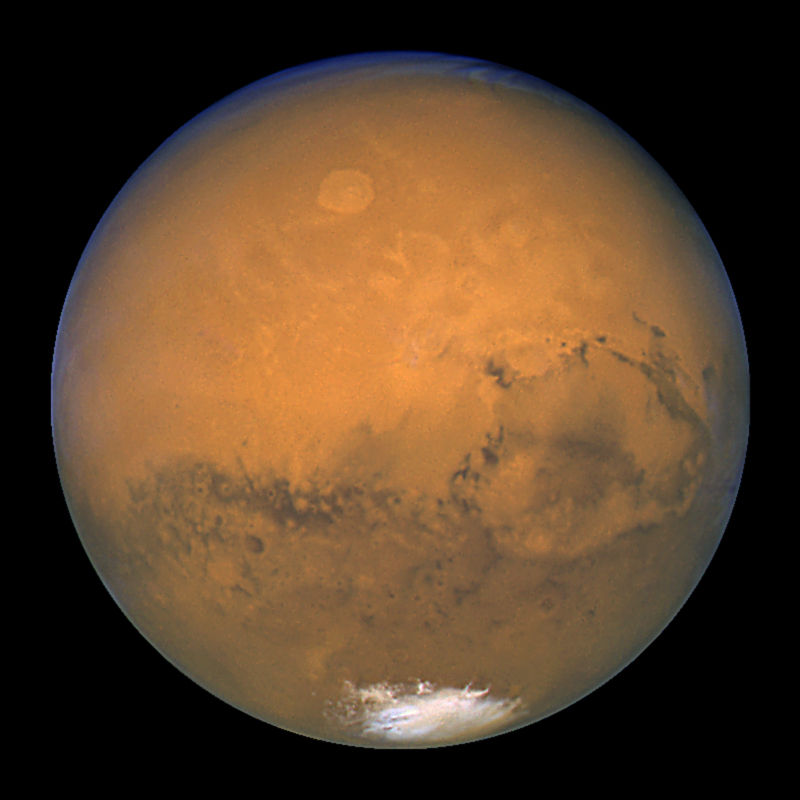

Earth's environment not only shapes those life-forms that evolve, but the planet actually evolves and changes in response to those organisms. So if life is lurking on Mars, researchers need to look for evidence of life modifying Red Planet habitats, Nathalie Cabrol said here on Dec. 14 at the annual meeting of the American Geophysical Union's Carl Sagan Lecture.

"It's only recently we understood not only that the environment changes, but [also] life has an impact on how the environment can change," said Cabrol, who is a senior research scientist and director of the Carl Sagan Center at the SETI Institute in California, and who gave the lecture.

However, looking for evidence of changes caused by life-forms won't be easy, Cabrol said. Any exploration on Mars needs to look at the right scale to find evidence of life modifying its habitat, she said. [7 Most Mars-Like Places on Earth]

Habitability versus habitat

Recent voyages to Mars have yielded fairly conclusive evidence that the Red Planet harbors theoretically habitable areas, such as the Gusev and Gale craters. For instance, chemical exploration has revealed that at different points in Martian history, the planet had an abundance of the building blocks of life, such as carbon dioxide, nitrogen dioxide, hydrochloric acid and methane, Cabrol said. River deltas and ancient tsunami deposits reveal that Mars had a water column and even, briefly, a primeval ocean. Rock weathering and hydrothermal geological activity may have provided the necessary chemical energy for life, she said.

But simply being habitable is very different from actually having a habitat, she said.

"Our planet is bio-obvious," Cabrol said. When looking from space signatures of life everywhere are visible everywhere, Cabrol said. "There is a strong message from our planet: 'I am alive.'"

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By contrast, Mars is also sending a strong message that life has not made a large impression on the Red Planet, she said.

Brief window of opportunity

Evidence suggests that the Martian atmosphere was declining as early as 4.1 billion years ago, and any surface water likely dried up long ago. With a thin atmosphere, bombardment by deadly cosmic radiation and likely no modern flowing water, any life that emerged on Mars likely did so very early on in the planet's history, during a time known as the Noachian period (from 4.1 billion to 3.7 billion years ago), Cabrol said. If that life is still hanging on, it likely went deep underground, where it is protected from Mars' current harsh environment, she said. [Boron Found On Mars For First Time By Curiosity Rover | Video]

"The window of time was very small," Cabrol said.

To understand what kind of Martian life-forms to look for, researchers need to understand the best Earth-based analog to the Martian Noachian period. This is Earth's Archean eon, between 4 billion and 2 billion years ago. During that period, all life on Earth consisted of primitive, single-celled creatures that lacked nuclei.

At that time, microbial mats of cyanobacteria living in shallow pools of water trapped grains of sediment to build up a kind of rock housing. Huge expanses of bulbous rock structures billions of years old have been found on Earth. Other primitive forms of life burrowed around in hydrothermal vents, creating signature cone-shaped structures, Cabrol said.

Earth analogs

Another way to determine what to look for is to find the most Martian-like places on Earth. The hyper-arid, high-altitude Atacama Desert, which, gets just 0.6 inches (15 millimeters) of rainfall a year but used to be much wetter, is exposed to punishing ultraviolet radiation and has active geothermal features such as hot springs.

"If you want to find the microbe, you have to become the microbe. Very early on, you need to shelter — you need to adapt and you need to survive," Cabrol said. Microbes would also have to "organize around oases and organize a lot faster."

These Martian oases could be similar, in some ways, to the evaporating lakes, salt flats and hot springs of the Atacama, Cabron said.

Ancient creatures in these Martian environments would likely be extremophiles or superbugs that are highly adaptive, and are possibly very quick to form symbiotic communities, Cabrol said.

While structures that could provide microbial habitats might be found on Mars, researchers will have to know where to look in the first place, Cabrol said. They won't get many opportunities to sample in many places, she said. Finding the tools with the resolution to identify those habitats will also be challenging, Cabrol added.

However, drones that can fly up and down to image the area at different scales could reveal some of the fine detail that provides clues for ancient life, she said.

And some tools already heading out on the Mars 2020 mission could reveal evidence of potential habitats. For instance, Cabrol showed images of Gusev Crater. Pictures of that feature initially lacked the resolution to reveal any evidence of habitat. But after looking at the light spectra reflected, "The spectra are telling us this is something that could be related to hydrothermal activity and constructs," Cabrol said. "There's only one way of knowing — it's to go back."

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tia is the assistant managing editor and was previously a senior writer for Live Science, a Space.com sister site. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com and other outlets. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a graduate certificate in science writing from UC Santa Cruz and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of a team at the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel that published the Empty Cradles series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the 2012 Casey Medal for Meritorious Journalism.