Space Shredder: Sun May Be Tearing Asteroids Apart

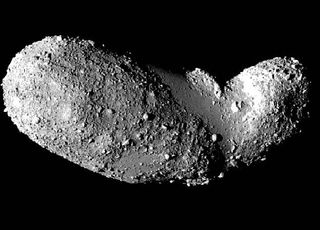

With a cloud of trailing debris, a rocky object known as 3200 Phaethon straddles the line between asteroid and comet. But the space rock's days, it seems, might be numbered.

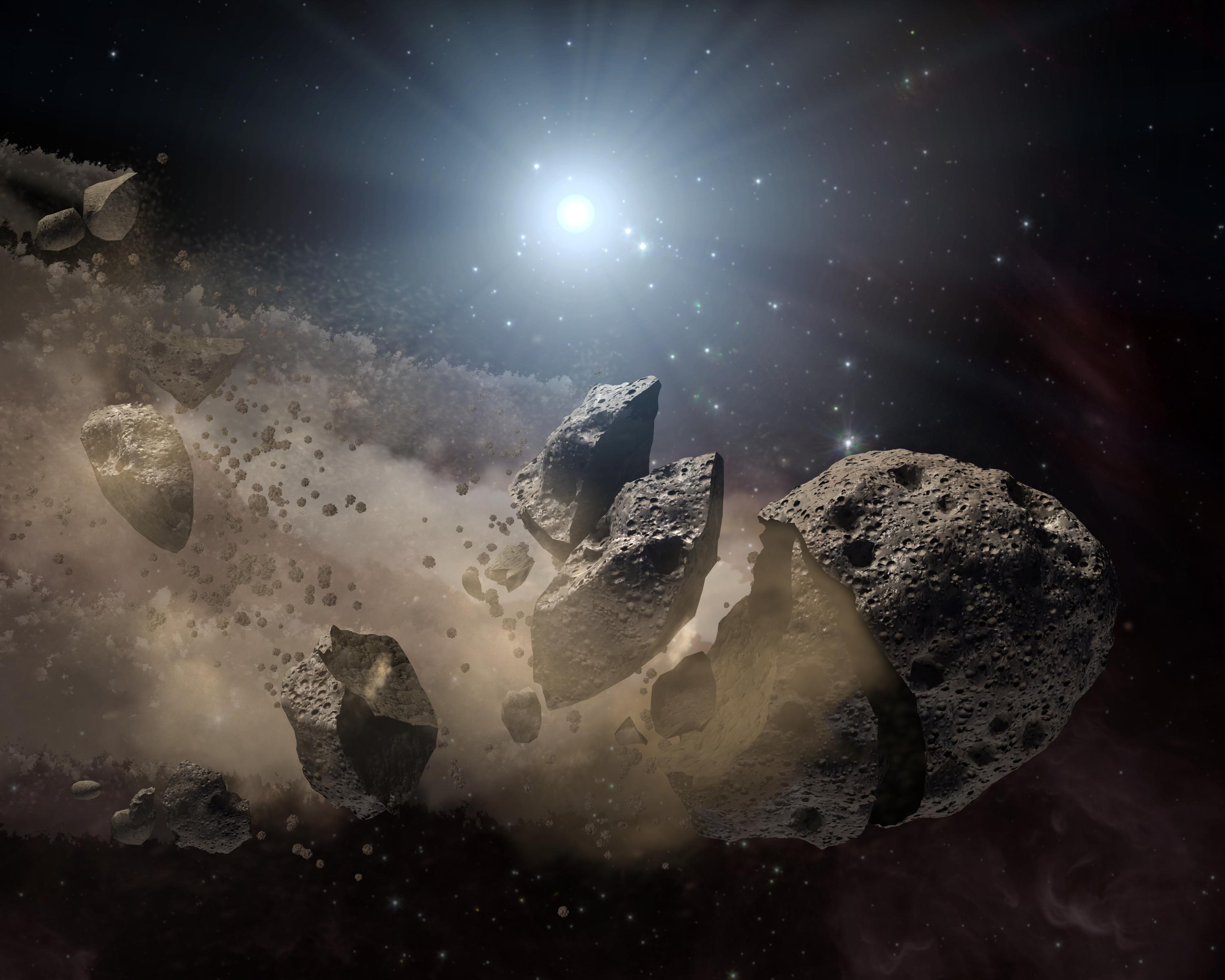

New research suggests that the sun may be slowly shredding Phaethon to pieces due to its close orbit. The same may be happening to another close-orbiting object.

"Phaethon may be a breakup in slow motion," Paul Wiegert, an astronomer at the University of Western Ontario in Canada, said at the Division of Planetary Sciences meeting in Pasadena, California. Wiegert used the Canadian Meteor Orbit Radar (CMOR) to track bodies 1 meter (3.3 feet) wide and smaller. As Phaethon orbits the sun, it appears to be breaking apart and then reforming, Weigert's study found. [Potentially Dangerous Asteroids in Images]

Asteroid on the brink

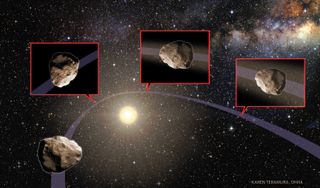

As 3200 Phaethon orbits the sun, it comes closer than any other named asteroid, occasionally traveling half as far away as the orbit of Mercury (which on average is about 35 million miles, or 58 million kilometers) before returning nearly as far out as Earth (which orbits at 93 million miles, or 150 million km). Along the way, the space rock drops off the material that feeds the Geminid meteor shower that peaks in December.

In 2010, scientists realized that Phaethon displayed characteristics similar to a comet as well as an asteroid, producing a tail of material that led to its classification as an active asteroid. Some active asteroids are suspected of forming tails like comets, because they have ice beneath the surface, but Wiegert proposed that Phaethon's debris trail instead results from the rock's sun-skirting orbit.

For nearly two decades, astronomers thought the near-Earth objects (NEOs) that strayed too close to the sun wound up swallowed by the star. Earlier this year (2016), however, Mikael Granvik, an astronomer at the University of Helsinki, revealed that many asteroids instead break into pieces when they spend too much time in the region of space within 10 times the sun's diameter.

Granvik's research suggests the catastrophic breakups of asteroids happen too far away to be explained by tidal effects from the sun. While the precise method remains uncertain, he and his colleagues proposed three possibilities.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Asteroids could be heated by the sun and thus crack, releasing grains that the solar radiation then strips. Another explanation is that solar particles or energy released as material jumps from solid to gas could cause asteroids to rapidly spin until gravity can no longer hold them together. The third option is that volatile materials jumping from solid to gas could create enough pressure to blow the asteroid up from within.

Tracking asteroid breakups

Wiegert and his colleagues used several years of observations taken by CMOR to examine whether the environment around the sun showed signs of super-catastrophic asteroid disruption. They found that the kilometer-size (0.6 miles) asteroids break up into surprisingly small chunks of debris.

"Asteroids don't break up into meter-sized chunks," Weiser said. "Any meter-sized bodies delivered by near-Earth asteroids are soon destroyed as well."

Instead, the material breaks into millimeter-size (0.04 inches) pieces that continue to orbit the sun, the researchers found.

That means an asteroid like Phaethon could be slowly tearing itself apart as it draws too close to the sun. When in a close orbit, such a rock begins to collapse, but as it moves away, it could be coalescing again.

"It may be an asteroid going to the brink [of catastrophic breakup] and then retreating," Wiegert said.

Still, the observations can't confirm the asteroid's slow breakup, he said. It is still possible that Phaethon acts like a comet, with icy material trailing off the surface to create the debris cloud, Wiegert said.

Phaethon isn't the only oddity. At the same conference, Granvik presented evidence that the Comet 322P/SOHO 1 may also be suffering from super-catastrophic disruption. "The question is, 'Is this a really a comet?'" Granvik said. Earlier this year, a team of scientists published research suggesting the comet may actually be an asteroid.

Although the object is active, observations suggest that it is denser than any known comet and that its activity is driven by a different process than other comets, whose tails form as they lose ice.

Phaethon and 322P aren't enough to satisfy Granvik, he said, explaining that he and his colleagues are working to identify other potentially disrupted asteroids in the process of falling apart.

"You always want more," he said.

Follow Nola Taylor Redd on Twitter @NolaTRedd or Google+. Follow us at @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and enjoys the opportunity to learn more. She has a Bachelor’s degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott college and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. In her free time, she homeschools her four children. Follow her on Twitter at @NolaTRedd