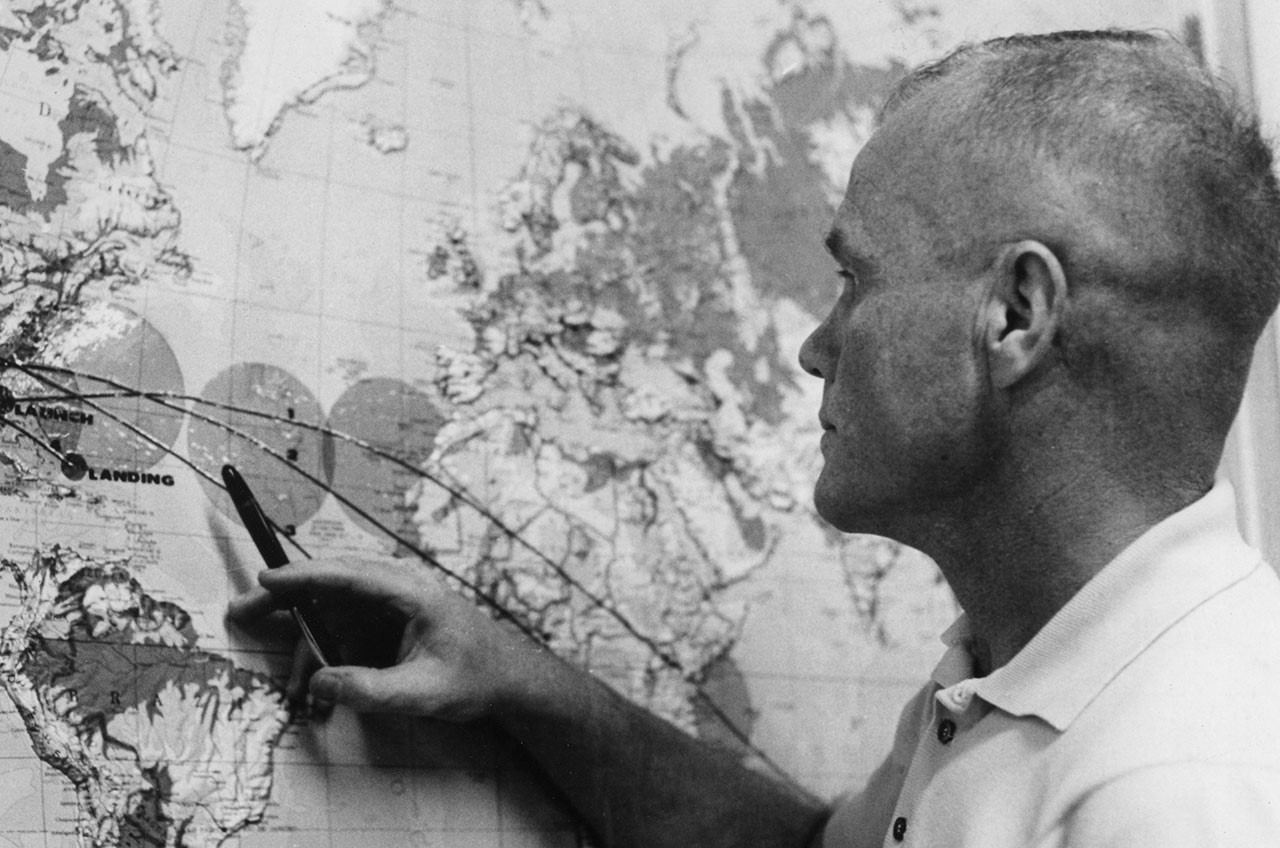

'Hidden Figures': When Did John Glenn Ask for 'the Girl' to Check the Numbers?

"Get the girl to check the numbers."

With those seven words, spoken by astronaut John Glenn before he became the first American to orbit Earth in 1962, Katherine Johnson's role in history changed.

A "human computer" assigned to NASA's Flight Research Division at Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia, Johnson was the African-American, then-44-year-old "girl" who was the subject of the astronaut's directive. As such, she set about double checking the trajectory calculated by her electronic counterpart: room-size IBM 7090 computers at Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

"If she says the numbers are good, I am ready to go," said Glenn, according to Margot Lee Shetterly, citing Johnson, in her book "Hidden Figures" (William Morrow, 2016) which served as the basis for the 20th Century Fox movie by the same title opening wide in U.S. theaters on Friday (Jan. 6).

That brief exchange, and the work Johnson did as a result of it, is a pivotal scene in the feature film, which stars Taraji P. Henson as the mathematician and Glen Powell as the astronaut. Like most "based on true events" films though, "Hidden Figures" takes certain liberties with the history.

"Those calculations for John Glenn took three days," said director Ted Melfi. "We can't do that in the movie, so even though [Johnson] is a math genius, she is not that much a genius."

"So yes, it took her 25 seconds in the film," said Melfi.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Shetterly writes that it actually took Johnson a day and a half to complete the calculations. But whether it was 36 or 72 hours, there is a potentially bigger question: When did Glenn ask for "the girl" to check the computers' numbers?

That piece of paper

In "Hidden Figures," the movie, Johnson (Henson) rushes to complete the math while Glenn waits on the launch pad. She then runs to hand off her report to Mission Control (in real life, Johnson was in Virginia for the launch, while the flight controllers were at Cape Canaveral in Florida).

Shetterly writes in her book that Glenn, who died on Dec. 8 at the age of 95, conducted a final check of his Mercury-Atlas 6 mission flight plan during the three days that led up to his launch on Feb. 20, 1962. It is within that context that she describes Johnson making the calculations, but that may or may not be when it occurred.

"Out of all of the things that I was trying to track down, this was the one," Shetterly told collectSPACE in an interview. "I spoke to some of the guys in Houston, with Katherine, and [searched through] documents. I cannot even tell you how many boxes of the Project Mercury reports, all of the computer printouts, I went through trying to find that exact thing."

Johnson told Shetterly it happened "weeks before" Glenn's launch, but her account, recalled more than 50 years after the event, "sort of moved around a little" over the course of her interviews.

"As best as I can tell and looking at all the details, her oral history testimony and NASA documents, it was some point very close to the launch in 1962, but I could never get the final date," stated Shetterly. "I have gotten close to it, but I haven't found that piece of paper that said it happened on this date, at this time, these many days before the launch."

Of days and dates

The question of when might be further complicated by the history of Glenn's flight.

The first American to orbit Earth lifted off on Feb. 20, 1962, but that came after two months of false starts. Glenn first got ready to launch by entering quarantine at the Cape in December 1961.

"NASA hinted that the flight might occur before Christmas," Glenn wrote in his 1999 memoir. "Bob [Gilruth, head of the Space Task Group] knew it wouldn't hurt the agency if the president could give a Christmas present to the country in the form of an orbital flight."

That gift however, was not to be. Technical problems with Glenn's Mercury capsule, Friendship 7, slipped the flight to the next month. NASA announced a date of Jan. 16, 1962, but that was postponed due to issues with the propellant tanks for the mission's Atlas rocket.

On Jan. 27, after at least one delay for poor weather and another for technical concerns, Glenn proceeded through a pre-flight physical, put on his silver spacesuit, ascended the launch tower and boarded his spacecraft for launch.

"I lay there on my back in the contour couch for nearly six hours, wishing that the gantry would pull back, signaling a break in the clouds and imminent liftoff," Glenn wrote. "But they didn't break, and the launch window closed."

A new attempt on Feb. 1 was called off after it was found that a fuel leak had soaked an insulation blanket inside the Atlas. Two weeks later, the weather scrubbed tries on Feb. 14 and 16.

Finally, the weather improved, and Friendship 7 lifted off at 9:47 a.m. EST on Feb. 20, 1962.

So, with all those stops and starts, why would Glenn only become concerned with the computer-generated numbers for his orbital trajectory on what turned out to be his last, successful attempt? After all, had the weather cooperated, he might have lifted off as early as a month before without the benefit of Johnson's double-check.

Time to figure

Had that happened — had Glenn flown his three orbits on Jan. 27, and were all other conditions equal — he probably would have been okay. Johnson's math matched the IBM, establishing the computer (the electronic one) was reliable.

As to the timing, at least two possibilities exists. Johnson could have performed the math earlier then she recalled, such that her verification came prior to the January launch attempts (or maybe even for the December pre-Christmas target), or, perhaps, the delays gave Glenn the extra time he needed to think through all the possibilities. [Incredible Life of NASA's Katherine Johnson - By the Numbers]

One detail that might bolster the latter scenario concerns how Glenn got the camera he used on board Friendship 7. According to his memoir, Glenn purchased the automatic camera at a Cocoa Beach drugstore in January, after his launch campaign had begun.

The delay from December gave Glenn the time to further consider the necessity of flying a camera after NASA had initially rejected the idea. Maybe the extra days and weeks also gave Glenn the time to recall the "girl" whose figures preceded the computers.

See more photos from "Hidden Figures" and of the real Katherine Johnson and John Glenn at collectSPACE.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2016 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.