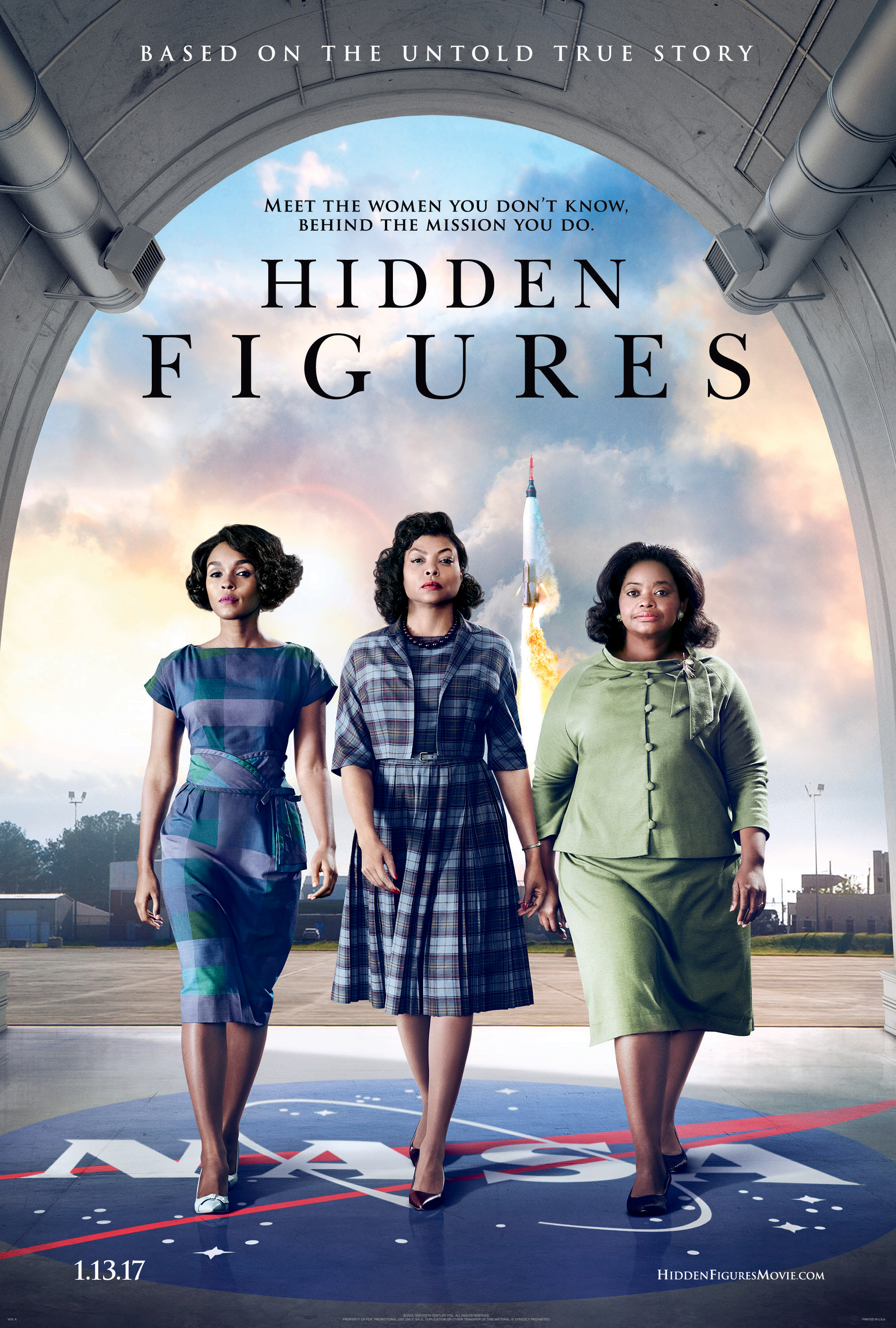

'Hidden Figures' Explores NASA and Civil Rights History

Before filming the movie "Hidden Figures," which will be widely released Jan. 6, the cast and crew studied up on the history of NASA in the 1960s and America's civil rights movement to immerse themselves in the lives of those who worked for the space agency during the height of the space race — a time when racial segregation was still legally enforced in the United States.

Space.com spoke with the film's director and lead actors to ask how they prepared for the most challenging aspects of getting it right.

In addition to re-creating the feel of NASA's Langley Research Center in Virginia on set in Atlanta, the creators strived to get the details right, using actual artifacts from the time period or very close replicas.

"We re-created NASA's mission control with the help of Wynn Thomas, our production designer, and we used NASA archival footage and NASA archival photos and a lot of help from our historians at NASA," Ted Melfi, the film's director, told Space.com. "We basically duplicated it exactly the way it was." ['Hidden Figures' Movie Probes Little-Known Heros of 1960s NASA (Gallery)]

Additional touches also connected the film's set with Langley. For instance, two paintings on the set depicting the history of air travel were actual paintings that hung in Langley's main administration building during the 1960s (the third actual painting was damaged, so it was missing from the set).

Beyond the physical location, the actors worked to place themselves in the early 1960s, internalizing what that meant for the burgeoning field of spaceflight and for the civil rights movement.

"I had all the actors watch a great NASA documentary called 'When We Left Earth,' Melfi said. "It's just a great look at the entire space program, but the first section is the Mercury missions," which sent the first American astronauts into space, Melfi said. "[I also assigned] a civil rights documentary called 'Eyes on the Prize.'"

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Melfi had the actors look through civil rights images by photographer Gordon Parks, as well, to find the movie's place in history.

Taraji Henson played Katherine Johnson, the mathematician at the film's center, and the actress had more than background research to work with; Henson met with Johnson, who's 98 years old, to get a feel for the character and how the mathematician viewed her time at NASA.

"Katherine Johnson is still very much alive … so I have to meet her, first thing first," Henson said. "What I got from her was her humility, her selflessness. She never once said, 'I.' She said, 'We.'" Henson said she tried to bring that selflessness to her depiction of Johnson.

Discussing the most challenging parts to film, Octavia Spencer, who played Dorothy Vaughan, told Space.com that individual scenes weren't challenging, but that it took some effort to place herself in the overall mind-set of the era.

"The time in our history that women, African American people, didn't have a voice in diplomacy, they didn't have the right to vote — the entire time was challenging, and therefore having the camaraderie with my castmates let me get beyond that," she said.

"What was challenging for me was all that running in heels," Henson added. "And I have bad knees … and then we had to run in the rain. I should have considered that when I read the script."

Janelle Monáe played Mary Jackson, who takes steps to become an engineer over the course of the film, including suing to gain access to required night classes at a segregated school.

"As Octavia mentioned, the mind-set [was the biggest challenge]. Mary didn't have the freedom of speech that we have today, and her brothers and sisters were being lynched for merely looking at a white person in a way that they may not have deemed to be respectful," Monáe said. "So I had to be very strategic. I had to go in and look at it like a chess game — how can I get this judge to empathize with me? How can I connect?

"She had to study her enemy, and so I had to really problem-solve how to get what I needed," Monáe said. "Ultimately, she did prevail — she did win."

To research his character, an engineer who wasn't based on any historic individual, Jim Parsons studied the career paths and backgrounds of real engineers who were a part of the Space Task Group, in order to create an original character who would be a credible product of that time period.

"I felt pretty clear pretty quickly about what my role was in the telling of the story, which was to be an impediment to somebody," Parsons said. "The chance to engage in scenes with somebody where you are being an impediment to them is actually enjoyable, because there's a friction to it. But I was very grateful to play what I felt was an important part of the progress of the story, even if it wasn't necessarily a shining example of humanity always."

Throughout scriptwriting and filming, the movie's creative team consulted with NASA to ensure that details about the mathematics and science, as well as about how the organization worked, were true to life. The filmmakers simplified or synthesized some things for the film, Melfi said, like Parson's engineer character, or the head of the Space Task Group, played by Kevin Costner, whose character was an amalgam of a few different directors. But the team tried to capture the essence of the women's stories, Melfi said.

"I think the most important thing to get right historically [for] this movie was the real story about these three women and be true to their experience, both the struggles they had as well as the successes they had," said Bill Barry, NASA's historian. "I think that was a central part, and I think the movie's done a spectacular job of being true to the real story of these women and their struggles."

In filming the women's story, the actors said they hope to reveal truths about the time period as well as the extraordinary accomplishments of the women portrayed in the movie.

"It's our history, and we would do well to know more about our history," Costner told Space.com. "It can be thrilling. It can be embarrassing. There can be points where you're ashamed, but you can also be thrilled and realize that you can be part of history, too, by altering the way you're going to behave going forward."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.