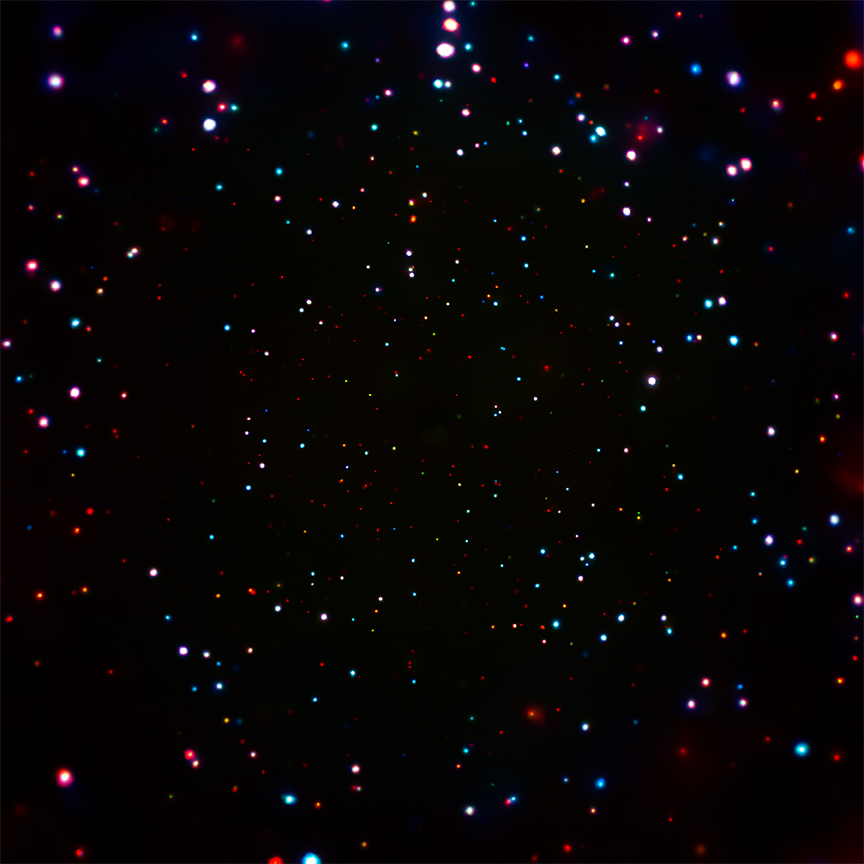

Deepest-Ever X-Ray Image of Space Captures Countless Black Holes

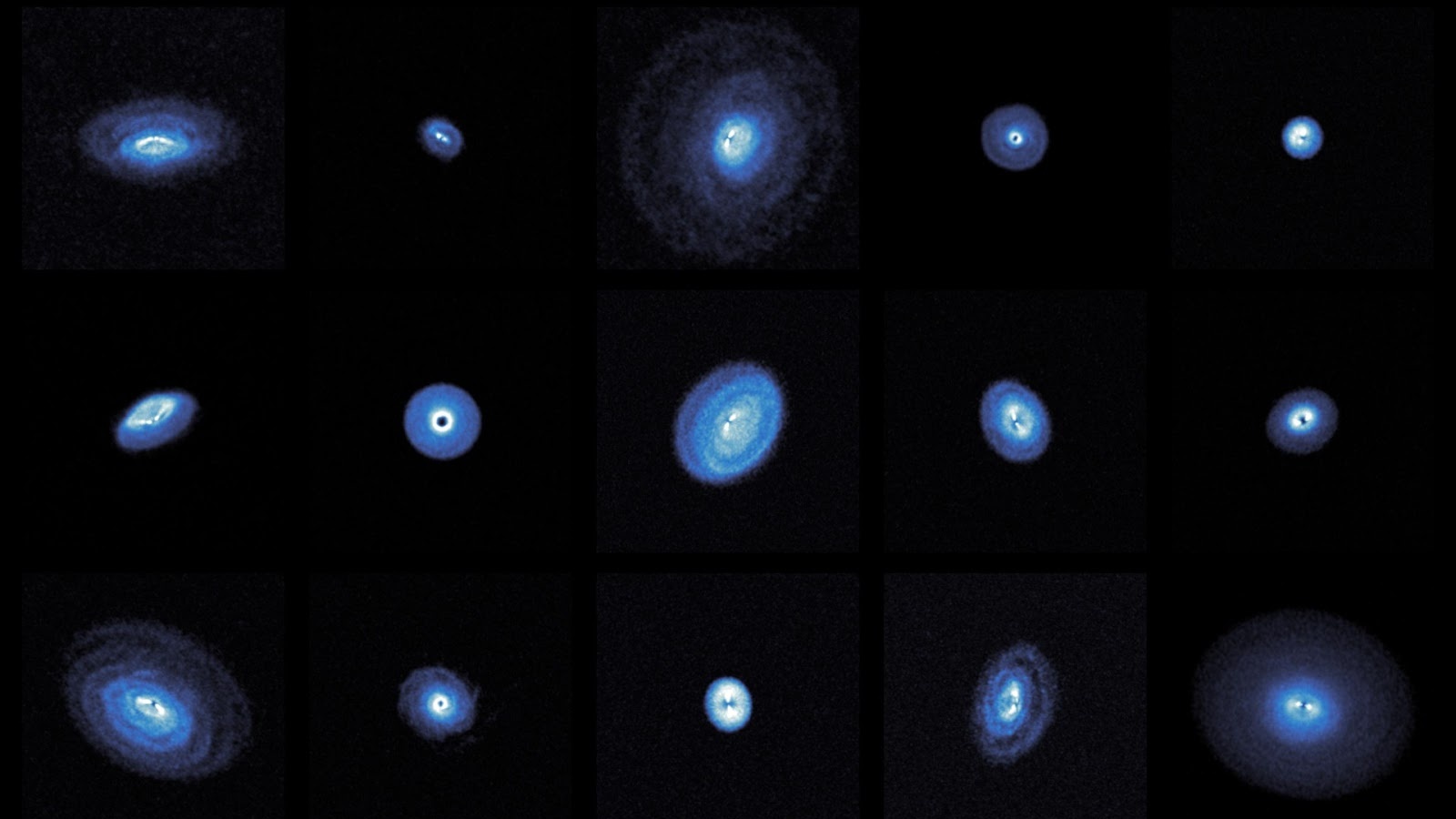

Huge numbers of supermassive black holes are visible in a stunning new photo that astronomers said is the deepest X-ray image of the sky ever captured.

The concentration of these light-gobbling monsters in the central region of the photo is unprecedented — the equivalent of 5,000 supermassive black holes over an area the size of the full moon, or 1 billion if extended across the entire night sky, researchers said.

"With this one amazing picture, we can explore the earliest days of black holes in the universe and see how they change over billions of years," Niel Brandt of Pennsylvania State University, who led a team of researchers studying the image, said in a statement. [Images: Black Holes of the Universe]

The image incorporates about 80 days' worth of data collected by NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory spacecraft and covers a patch of sky 16 arcminutes across — about one-half the width of the full moon as seen from Earth. About seven out of every 10 objects in the photo are supermassive black holes, which lie at the hearts of galaxies and contain 100,000 to 10 billion times the mass of the sun, study team members said.

Chandra detects these black holes by spotting the X-ray radiation emitted by material spiraling toward the objects' event horizons, the points beyond which nothing, not even light, can escape.

"It can be very difficult to detect black holes in the early universe, because they are so far away and they only produce radiation if they're actively pulling in matter," study team member Bin Luo, of Nanjing University in China, said in the same statement. "But by staring long enough with Chandra, we can find and study large numbers of growing black holes, some of which appear not long after the Big Bang."

Analyses of this treasure trove suggest that supermassive black holes grew in bursts, rather than gradually, in the first 1 billion to 2 billion years after the Big Bang, researchers said. In addition, the "seeds" of these behemoths are likely quite heavy, with masses between 10,000 and 100,000 times that of the sun, researchers said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

These findings could help explain a cosmic mystery: how supermassive black holes came to populate the early universe, despite not having much time to grow.

The team also determined that most of the X-ray emissions from massive, extremely distant galaxies — those 12 billion to 13 billion light-years away from Earth — likely came from stellar-mass black holes. These objects form after the death and collapse of stars much larger than the sun, and contain up to a few dozen solar masses.

"By detecting X-rays from such distant galaxies, we're learning more about the formation and evolution of stellar-mass and supermassive black holes in the early universe," said study team member Fabio Vito, who's also based at Penn State. "We're looking back to times when black holes were in crucial phases of growth, similar to hungry infants and adolescents."

The researchers presented their findings today (Jan. 5) at the 229th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Grapevine, Texas.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.