The moon is a very old soul, it turns out.

A new analysis of lunar rocks brought to Earth by Apollo astronauts suggests that the moon formed 4.51 billion years ago — just 60 million years after the solar system itself took shape.

Some previous studies have come up with similar estimates, while others have argued for a younger moon that coalesced 150 million to 200 million years after the solar system was born. The new finding, which was published today (Jan. 11) in the journal Science Advances, should settle this long-standing debate, team members said. [How the Moon Formed: 5 Wild Lunar Theories]

"We are really sure that this age is very, very robust," lead author Melanie Barboni, a researcher in UCLA's Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences Department, told Space.com.

The moon's birth

Astronomers think the moon was born after a Mars-size body (or a series of such big objects) slammed into the early Earth. Some of the material blasted into space coalesced to form Earth's nearest neighbor, the thinking goes.

But it's been hard to pin down exactly when this impact, or these impacts, occurred, Barboni said. That's because the rocks collected by Apollo astronauts and studied by scientists tend to be breccias — jumbles of different rock types mashed together by meteorite strikes (which are very common on the lunar surface, because the moon has almost no atmosphere to burn up falling space rocks).

"You don't have pristine, old rock preserved on the moon," Barboni said. "That's one of the biggest problems — the whole-rock record on the moon is not there."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

So Barboni and her team decided to take a different tack. Rather than study entire rocks and hope they date all the way back to the moon's birth, the team dated the formation of the object's mantle and overlying crust.

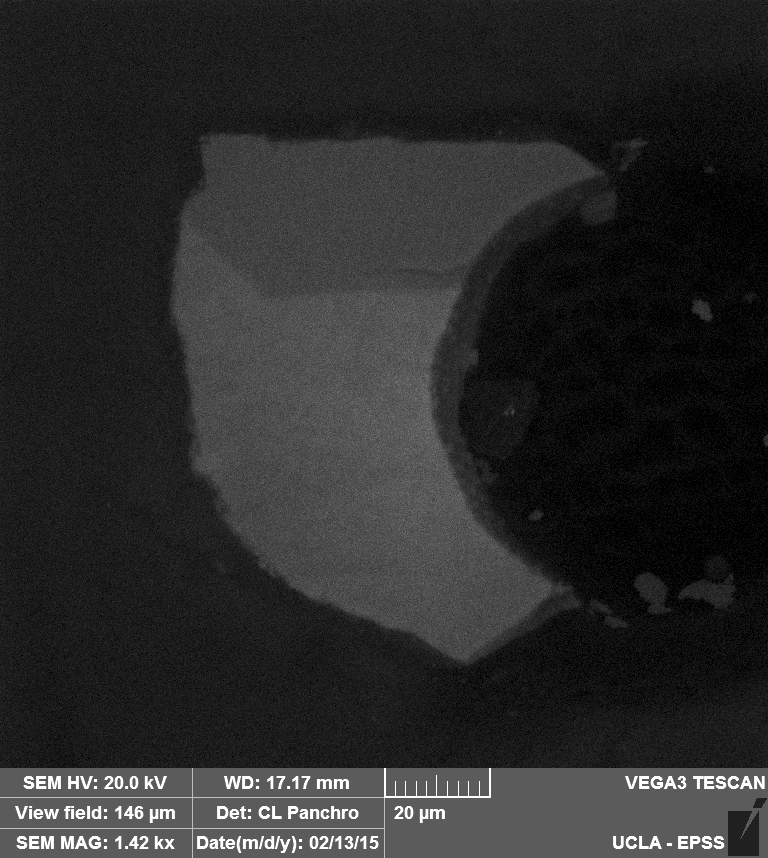

This "differentiation" occurred shortly after the giant impact(s), when a global liquid-magma ocean initially present on the moon cooled and solidified. And this solidification left a signal, Barboni said — a mineral called zircon.

"If you want to date this process, we use the mineral zircon, because that's the best time capsule you can find," she said.

The researchers studied zircon fragments in rocks collected by Apollo 14 astronauts in 1971. The team dated the samples radiometrically, by measuring how much of their uranium had decayed into lead, and how their hafnium had decayed into various "daughter isotopes." (Isotopes are variants of an element that have the same number of protons in their nuclei but different numbers of neutrons.)

The team's analyses show that the zircon fragments are pristine and ancient, dating back to the solidification of the magma ocean, Barboni said. The researchers also managed to correct for the influence of galactic cosmic-ray impacts, which can complicate dating attempts by injecting neutrons into samples, she added.

The age the team came up with for the moon — 4.51 billion years, give or take 10 million years — should therefore stand the test of time, Barboni said.

"We were able to correct for everything that was a problem before, the reasons people said zircon couldn't be used," she said.

The moon's advanced age also makes sense from a dynamics point of view, especially if the giant-impact(s) theory is correct, Barboni said. That's because more impactors were flying around in the solar system's very early days than 100 million years or so later, she said.

Ties to life on Earth

The new result should be of interest to any astronomer who wants a better understanding of how the moon, Earth and solar system in general formed and evolved, according to Barboni.

For example, life on Earth appears to have gotten a foothold by at least 4.1 billion years ago. This extreme antiquity may seem surprising, given that the moon-forming impact(s) likely heated up Earth tremendously, completely reshaping and remaking the planet's surface.

But it's less surprising with an old moon than with a young one, Barboni said.

"That makes much more sense, if actually the Earth started evolving from 4.5 [billion years ago] rather than the Earth evolving from 4.3 [billion years ago]," she said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.