The Universe Is Expanding Surprisingly Fast

The universe really is expanding faster than scientists had thought, new research suggests.

Astronomers have pegged the universe's current expansion rate — a value known as the Hubble constant, after American astronomer Edwin Hubble — at about 44.7 miles (71.9 kilometers) per second per megaparsec. (One megaparsec is about 3.26 million light-years.)

This newly derived number is consistent with a calculation that was announced last year by a different research team, which was led by Nobel laureate Adam Riess. But it's considerably higher than the rate that was estimated by the European Space Agency's Planck satellite mission in 2015 — about 41.6 miles (66.9 km) per second per megaparsec. [In Photos: Quasars and the Expanding Universe]

The cause of this discrepancy is unclear at the moment, scientists said. However, the different types of data these various groups analyzed may provide a clue.

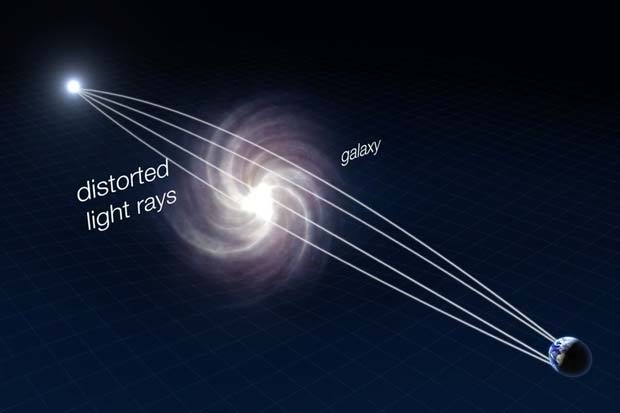

To arrive at the new estimate, the research team — led by Sherry Suyu of the Max Planck Institute for Astrophysics in Germany and Frédéric Courbin of the École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne in Switzerland — studied how massive nearby galaxies warp the light streaming from distant, superbright galactic cores known as quasars. Suyu, Courbin and their colleagues used NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and Spitzer Space Telescope, as well as a number of ground-based instruments, to do this work.

"Our method is the most simple and direct way to measure the Hubble constant, as it only uses geometry and general relativity — no other assumptions," Courbin said in a statement.

Riess and his team analyzed Hubble observations of two different types of "cosmic yardsticks" — Type Ia supernovas (stellar explosions of consistent luminosity) and Cepheid stars, which pulse at rates that are related to their true brightness.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Planck number, however, is a projection that's based on the spacecraft's measurements of the cosmic microwave background — the light left over from the Big Bang that created the universe 13.82 billion years ago.

So the differences in the Hubble constant estimates may reflect something that astronomers don't understand about the early universe, or something that has changed since that long-ago epoch, scientists have said. For example, it's possible that dark energy — the mysterious force that's thought to be driving the universe's accelerating expansion — has grown in strength over the eons, members of Riess' team said last year. [7 Surprising Things About the Universe]

The discrepancy could also indicate that dark matter — the strange, invisible stuff that astronomers think vastly outweighs "normal" matter throughout the universe — has as-yet-unappreciated characteristics, or that Einstein's theory of gravity has some holes, they added.

"The expansion rate of the universe is now starting to be measured in different ways with such high precision that actual discrepancies may possibly point towards new physics beyond our current knowledge of the universe," Suyu said in the same statement.

Suyu, Courbin and their colleagues present their results in a series of five papers that will be published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.