50th Anniversary of Apollo 1 Fire: What NASA Learned from the Tragic Accident

This time of year is always a somber one for NASA as the space agency remembers the astronauts who died in three horrific spaceflight disasters.

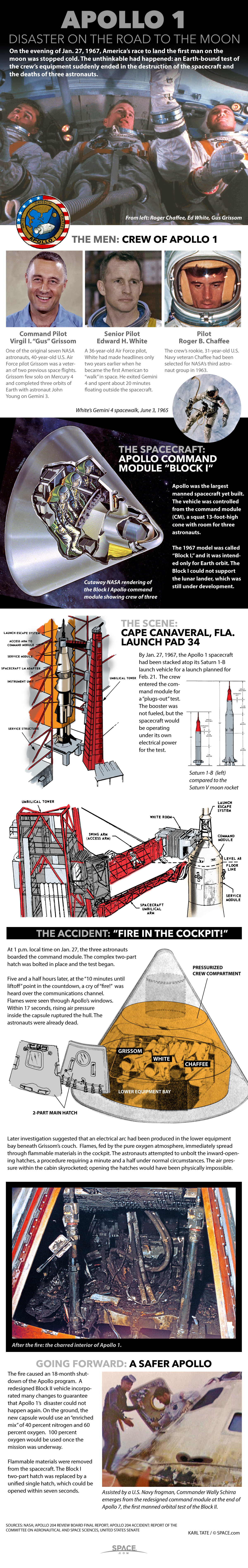

Today (Jan. 27) marks the 50th anniversary of the first major, deadly disaster for the U.S. space program: the Apollo 1 fire. On Jan. 27, 1967, a fire erupted inside the Apollo command module during a preflight rehearsal test, killing three astronauts who were trapped inside.

Coincidentally, two other deadly spaceflight accidents that occurred decades later happened around the same time of year. On Jan. 28, 1986, the space shuttle Challenger exploded 73 seconds after liftoff, killing all seven crewmembers. Tragedy struck again on Feb. 1, 2003, when the space shuttle Columbia broke into pieces as it returned to Earth, killing another seven astronauts.

Days of Remembrance

To honor the brave astronauts who lost their lives in the line of duty, NASA holds a series of ceremonies every year. Today, NASA's Kennedy Space Center in Florida will unveil a new Apollo 1 tribute in its visitor complex at the Apollo/Saturn V Center. The ceremony will be open to the public, and you can watch the live webcast here starting at 11 a.m. EST (1600 GMT).

For its official "Day of Remembrance" on Tuesday, Jan. 31, NASA will hold an observance and wreath-laying ceremony at Arlington National Cemetery in Virginia by the graves of Apollo 1 astronauts Gus Grissom and Roger Chaffee.

Although the coming days may be a time of mourning for NASA and the rest of the nation, it's worth acknowledging that these terrible tragedies also served as crucial learning experiences that helped to make human spaceflight safer for the astronauts who later flew into space.

Apollo 1: NASA's first tragedy

The Apollo 1 mission was supposed to be the first of several crewed flights NASA conducted to prepare for its first moon landing. But the spacecraft never made it off the launchpad, and it was destroyed nearly a month before its planned launch date, Feb. 21, 1967. [Photos: The Apollo 1 Fire]

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

On Jan. 27 at 1 p.m. EST (1800 GMT), the three crewmembers entered the Apollo control module for a launch countdown simulation called a "plugs-out" test, which would determine whether the spacecraft was capable of operating on internal power. The Saturn IB rocket that would have launched the crew module into Earth's orbit was not involved in this routine and seemingly safe prelaunch test. Needless to say, the spacecraft flunked that test. Many people at NASA felt that it wasn't ready for such a test to begin with.

The crew spent the entire afternoon sitting inside the space capsule while debugging problems, including a foul odor emanating from the oxygen tank and a faulty communication system. "How are we going to get to the moon if we can't talk between two or three buildings?" Grissom shouted from inside the capsule.

Grissom was "very vocal about the shortcomings of the spacecraft," and the crew often complained to higher-ups that the spacecraft was not ready, former NASA astronaut Tom Jones told Space.com. When Grissom realized that raising his voice wasn't making much of a difference, he famously picked a lemon from his citrus tree at home and brought it to Cape Kennedy (now known as Cape Canaveral), where he hung it on the flight simulator as a symbol of his frustration.

As the crew went over their checklist inside the module, suddenly, the spacecraft's interior became engulfed in flames. Heat caused the air pressure inside the spacecraft to rise, making it impossible for the astronauts to open the hatch, which was designed to open inward. After about 30 seconds, the spacecraft ruptured. NASA's ground crew tried desperately to rescue the astronauts, but they died of asphyxiation before rescuers were able to get them out of the spacecraft.

That stray spark appeared to have originated in a bundle of wires. But that was only the beginning of a series of critical mistakes that led to the fire; far more concerning was the abundance of flammable materials inside the spacecraft. Arguably the biggest mistake they made was to fill the air with pure oxygen rather than a mix of oxygen and nitrogen like the air of Earth's atmosphere. Pure oxygen made the spacecraft extremely flammable. Top that off with combustible materials — including Velcro, nylon netting, foam pads and bundles of wiring — and you have "fuel for a 100 percent oxygen environment," NASA historian Roger Launius told Space.com.

Launius said that people at NASA knew about the major design flaws, particularly the unsafe flammable materials inside the spacecraft, for two years before the accident happened. "So why didn't they figure this out beforehand, before somebody died?" Launius said. "That's something that has never been adequately answered in my mind."

Haste for space

It seems as though political pressure to get to the moon in the height of the space race might have led NASA officials to overlook some safety concerns in favor of beating Russia to the moon. "Back in the '60s, NASA was brand-new … and setting the goal of getting to the moon in less than nine years was pretty ambitious," Leroy Chiao, a former NASA astronaut, told Space.com.

Perhaps the Apollo 1 fire could have been prevented if the United States had not been caught up in a race to get to the moon. On the other hand, it's important to remember that NASA was attempting to do something that had never been done before, and that comes with an inherent risk, Chiao noted. "NASA was still learning," Chiao said. "In hindsight, it's easy to criticize NASA for the decisions that were made, but the reality is that they were still figuring it out."

Although NASA had put astronauts in space before, with its Mercury program and subsequent Gemini program, the first Apollo mission was not exactly a routine operation. "The Apollo was not a modified version of the Gemini spacecraft; it was a brand-new spaceship and it had about five years of development time, but it was not ready to fly by January," Jones told Space.com. "It had a lot of problems in development, assembly and testing."

This was no secret in the months leading up to the accident. The spacecraft had undergone several design changes that delayed the original planned launch date. A combination of political pressure and schedule delays created a recipe for disaster as NASA worked to undertake one of the most difficult and ambitious space missions in human history.

Heroes of Apollo 1

NASA lost three incredibly important astronauts in the Apollo 1 fire. Grissom was among the original Mercury astronauts and was the second American to fly to space. His crewmate Ed White became the first American to perform a spacewalk, which he did during the Gemini 4 mission in 1965. The third crewmember, Roger Chaffee, was a Navy lieutenant commander and a spaceflight rookie. Chaffee was looking forward to his first spaceflight and once said, "I think it will be a lot of fun."

Losing these brave astronauts was tragic, but some good did come out of the incident despite their deaths. NASA learned from the mistakes, and spacecraft are now much safer than they were then. Flammable materials no longer fill the inside of crew capsules. Hatches are now easier to open, so astronauts can escape in seconds in case of an emergency.

Grissom, White and Chafee died heroes because their tragedy was the wake-up call that NASA needed in order to prevent more potentially fatal incidents.

There will always be risks with human spaceflight, Chiao said, but it has certainly become safer over the years.

"I think it's important for everyone to not only respect the astronauts who are no longer with us, but to think about the space program and what it's done for us not only as a driver of technology but also — and I think more importantly — as something that gets young people excited and inspires them to dream big," Chiao said.

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that Grissom hung a lemon on the Apollo 1 spacecraft. Grissom hung the lemon on the Apollo Mission Simulator.

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.