Apollo 1: Three Stars Commemorate a Sad Anniversary

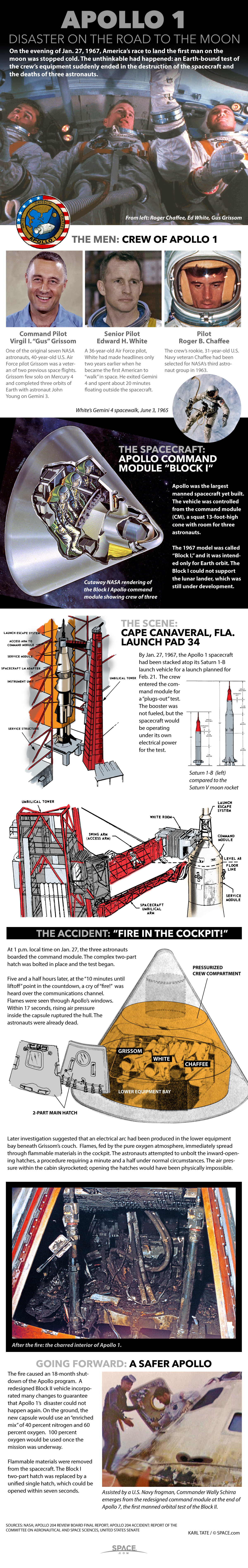

Today (Jan. 27) is a sad day for NASA, marking the 50th anniversary of when a flash fire occurred during a launch-pad test of the Apollo/Saturn space vehicle, which was being prepared for its first piloted flight. Astronauts Virgil I "Gus" Grissom, Edward H. White II and Roger B. Chaffee lost their lives when a fire swept through the command module, or "CM."

A nearly 10-week investigation determined that an electrical spark, occurring in an environment rich in pure oxygen inside the command module, ignited the fire. The blaze occurred during the early evening hours of Jan. 27, 1967 — also a Friday — at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station Launch Complex 34.

The flight of Apollo 1 was to be the first crewed mission of the Apollo program, with the ultimate goal of landing astronauts on the moon and returning them safely to Earth. Apollo 1 was scheduled to fly on a two-week mission on Feb. 21, 1967, but the tragic accident set America's space program back by some 20 months.

Today, the country can pause and remember these three heroic men who helped the United States take the first steps on its path to the moon. And in this evening's night sky, three stars will, in a way, serve as a commemoration of those lost astronauts. [Remembering the Apollo 1 Fire (Infographic)]

A "wonderful con"

The stars make an appropriate memorial because of their history in the astronauts' lessons on celestial navigation.

The Apollo spacecraft that ultimately took men to the moon used an inertial guidance system. This system continuously monitored the position and velocity of the space vehicle and, by way of a computer, provided navigational data or control without requiring the ship to constantly communicate with mission control back on Earth. One of the basic components of such a system was a set of gyroscopes to keep the spacecraft aimed in the right direction. But, periodically, gyroscopes will drift, requiring the astronauts to perform a recalibration procedure by sighting on specially selected stars.

NASA chose 37 navigational stars for the task, and from 1960 to 1975, a total of 62 NASA astronauts studied celestial navigation at the University of North Carolina's Morehead Planetarium and Science Center at Chapel Hill.

The planetarium director at the time, Tony Jenzano, was convinced that the astronauts NASA was planning to send into space — including Neil Armstrong, John Glenn, Alan Shepard and the crews from the Apollo lunar landings — needed to know the night sky just in case the navigation systems failed. In that event, these spacefarers would have to be reliant on their own knowledge and skills to land safely, Jenzano said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Jenzano was also well-known for having a wry sense of humor. Astronaut Walter Schirra revealed in his biography what he described as a "wonderful con" that Jenzano and astronaut Grissom pulled off. In 1966, Grissom created three new star names, and Jenzano quietly incorporated these three names onto NASA's star list without telling anybody, noting them on existing stars: Dnoces, Navi and Regor.

Innocently circulated

The astronauts also trained in star identification at Los Angeles' Griffith Observatory. The planetarium director at that time was Clarence C. Cleminshaw, a lawyer who became an astronomer and joined the Griffith Observatory when it was in its infancy. Cleminshaw was working on an article about navigational stars that would eventually appear in the September 1967 issue of the observatory's monthly magazine, the Griffith Observer, and he asked Grissom for a list of the guide stars that the astronauts would use in their flights to the moon.

Dnoces, Navi and Regor made the list.

Cleminshaw never questioned the origin of the three unusual monikers — and why should he? After all, it was Grissom, one of the original seven Mercury astronauts and a veteran of the Gemini space program, who provided the star list. That fact alone was more than enough to convince Cleminshaw to accept the three names.

And thanks to his article, other reputable publications innocently circulated the star list, in some cases even incorporating the names onto their own star charts. Sky & Telescope magazine was one example. Eventually, Grissom's three maverick stars earned the same respect as revered ones like Arcturus, Regulus and Antares.

Reversed appellations

But what did those odd names stand for?

Dnoces is the word "second" spelled backward, a reference to astronaut Edward White. "Second" had a special meaning for him on two counts. Not only was "second" part of his name (Edward H. White II), but he was also the second human to walk in space. Regor was Chaffee's first name in reverse, and Grissom decided to turn his own middle name (Ivan) around to create the name Navi. All three stars are simultaneously visible in the current midwinter sky for several hours, beginning from late evening on into the early morning hours.

Dnoces is Iota (ι) Ursae Majoris, the upper of a pair of stars marking the front paw of the Great Bear constellation. The star also has a proper Arabic name, Talitha, which dates back to around the year 500. This week, skywatchers can see this star around midnight, standing almost directly overhead, with the Big Dipper not far behind, tilted almost upside down high in the northeast.

Navi is in Cassiopeia, the Queen, which is riding low down in the northwest sky at around midnight. This star marks the middle of the "W" or "M" configuration formed by the zigzag row of the Queen's five brightest stars. Star atlases refer to the star as Gamma (γ) Cassiopeiae. Chinese astronomers referred to the constellation of Cassiopeia not as a Queen, but as a chariot driver, and Gamma bore the Chinese name "Tsih," which means "the Whip."

Lastly, "Regor" is Gamma (γ) Velorum in the constellation of Vela, the Sails. That constellation was once part of a much larger, albeit now-defunct constellation, Argo Navis, the Ship. This star also has an Arabic name, Al Suhail al Muhlif. Admittedly, Regor is easier to remember.

In their book "Short Guide to Modern Star Names and their Derivations" (Otto Harrassowitz, 1986), authors Paul Kunitzsch and Tim Smart pretty much figured out what Regor stood for. Without knowing the background behind the strange name, they wrote, "It is of uncertain derivation. … perhaps it is the reverse spelling of someone's name (Roger)."

This star is a splendid double star in binoculars or a small telescope, but only skims just above the southern horizon at around midnight as seen from midnorthern latitudes.

But today, now that the public knows of the true origins of these three bogus star names, most reference sources cite them as "disused or never really used." Still, it is with a touch of sad irony that Grissom's little practical joke ended up turning into an everlasting memorial of sorts to himself and his two crewmates on Apollo 1.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmers' Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Fios1 News in Rye Brook, New York. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.