Could Wormholes Really Work? Probably Not

Paul Sutter is an astrophysicist at The Ohio State University and the chief scientist at COSI Science Center. Sutter is also host of Ask a Spaceman, RealSpace and COSI Science Now.

Ah, wormholes. The intergalactic shortcut. A tunnel through space-time that allows intrepid travelers to hop from star system to star system without ever coming close to the speed of light.

Wormholes are a workhorse of sci-fi interstellar civilizations in books and on the screen because they solve the annoying problem of "Well, if we stuck to known physics, 99.99999 percent of the story would be as fascinating as watching people sleep."

But could we do it? Could we actually warp and bend space-time to make a convenient tunnel, making all of our galactic dreams come true? [Weird Science: Wormholes Make the Best Time Machines]

Short answer: not likely.

Long answer: Well, keep reading.

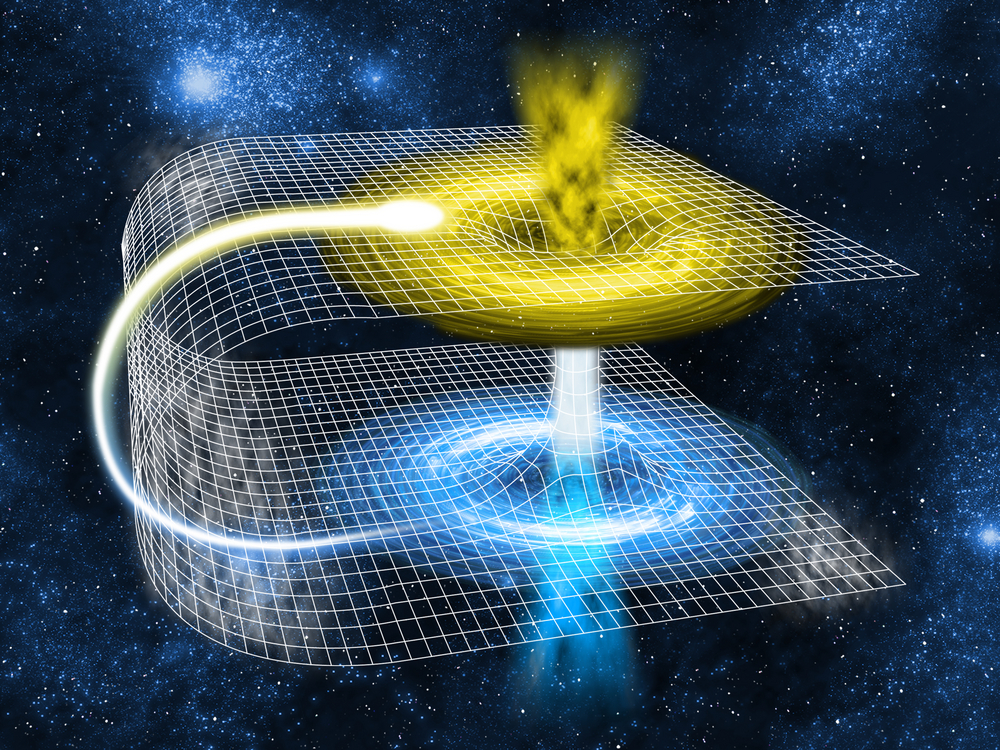

Beware the white hole

The concept of wormholes got its start when physicist Ludwig Flamm, and later Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen, realized that black holes can be "extended." When one goes about solving the fantastically complicated equations of general relativity, the machinery that predicts a black hole also predicts a phenomenon called a white hole. A white hole is pretty much what you think: Whereas a black hole's event horizon marks a region of space that once you enter you can't leave, it's impossible to enter a white hole's horizon, although anything already in there can escape.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That same mathematical machinery delivers a bonus, too: All black holes would be naturally "connected" to white holes via their singularities, making a tunnel through space. Woohoo, wormholes here we go!

Or not. While we have gobs of evidence for the existence of black holes, white holes appear to be mathematical fiction. There's no known process in our universe that would actually form them, and even if they did pop into existence, their natural extreme instability would snuff them right out again. [Watch: Wormhole instabilities.]

Oh, yeah, and the mechanism for making black holes — the collapse of massive stars — also automatically prevents the formation of a symbiotic white hole.

And even if they did form (and they don't), the extreme gravity of the mutual singularities would cause the wormhole tunnel to immediately stretch and snap much more quickly than anything could cross it.

Death by wormhole

But that doesn't stop anybody from playing a fun game of "what if." What if white holes could naturally form, or be constructed? What if we could stabilize them? What if we could attach a white hole's singularity to a black hole and make a wormhole? What if? What if? What if?

Well, for one thing, traveling down such a wormhole would really, really suck. Literally. The entrance to the wormhole — the "throat" — sits inside the event horizon of the black hole.

That's a problem.

The very definition of an event horizon — their very cosmique raison d'etre — is that once you enter them, you don't get to come out. No way, no how. It doesn't matter if there's a wormhole tunnel inside it — you don't get to leave.

Inside a black hole event horizon, you have only one destination: singularity town, the place of infinite density and soul-crushing gravitational forces.

So let's say you enter a wormhole. You can watch light from another patch of the universe filter in from the opposite side. If someone else jumps in, you can meet them and have some tea together. And you can die — miserably — as you careen into the singularity. [Chasing Wormholes: The Hunt for Tunnels in Space-Time]

Positively negative

Is there any way to make a working, even fun, wormhole, instead of a terrifying portal to inevitable destruction?

Surprisingly, yes. Well, not quite 100 percent absolutely "this is a normal part of our universe" yes. More like "if we play pretend" yes.

To construct a traversable wormhole, you need to overcome two important obstacles. First, the entrance to the wormhole has to actually sit outside the event horizon. That would allow you to enter the wormhole and blast through it to your faraway destination without fearing a "singular" encounter.

Second, the tunnel itself has to be stable and strong. It has to withstand the extreme gravity of the singularities and resist tearing apart when something flies down its length.

There is indeed a material that solves both problems. But that material has a problem all its own: It has negative mass.

That's right: mass, but negative. A ring of negative-mass material could be used to construct a fully functional and useful wormhole. Since the exotic nature of negative mass warps spacetime in a unique way, it "inflates" the entrance to the wormhole outside the boundary of the event horizon, and stabilizes the throat of the wormhole against instabilities. It’s not an intuitive result but the math checks out.

But could such a substance exist? We've mapped out a good chunk of the universe, and we've never seen negative mass. If it did exist, it would have some pretty weird properties. For example, following the math of Newton’s Laws with some minus signs tossed in, we find that a negative-mass particle would push on a positive-mass particle, while the positive-mass particle would pull on the negative-mass one. Set two opposite-mass particles next to each other, perfectly still, and the pair would start accelerating, zooming off without any input of force.

That seems like that might violate some sort of rule. [Watch: The problem of negative mass.]

What about the Casimir effect, the odd and fascinating attraction of two metal plates due to vacuum energy? That’s often trotted out as an example of the universe behaving badly, and a possible route to negative mass. But the Casimir force is characterized by local negative pressure (it pulls rather than pushes), not negative mass.Sure, we don't know everything there is to know about quantum gravity and the nature of space-time at super-duper-teensy scales. Could an advanced civilization discover the path to negative mass and manipulate gravity in just the right way? Would a breakthrough in physics point a way to fashioning wormholes?

Honestly, probably not. There are just too many things working against them. Working wormholes would violate so many aspects about known (and extremely well tested) physics that I think it's better to just work on other problems.

I know some people might accuse me of not being creative enough, but the universe doesn't care about our creativity. The tools of science are harsh but fair judges; if an idea doesn't work, it simply doesn't work. There are many varied and beautiful mysteries in our universe, and we certainly haven't unlocked all of the inner workings of the cosmos. But wormholes probably aren't one of them.

Learn more by listening to the episode "Wormholes - deal or no deal?" on the Ask A Spaceman podcast, available on iTunes and on the Web at http://www.askaspaceman.com. Thanks to @SkaTaTah and @bretthines61 for the questions that led to this piece! Ask your own question on Twitter using #AskASpaceman or by following Paul @PaulMattSutter and facebook.com/PaulMattSutter.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Paul M. Sutter is an astrophysicist at SUNY Stony Brook and the Flatiron Institute in New York City. Paul received his PhD in Physics from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign in 2011, and spent three years at the Paris Institute of Astrophysics, followed by a research fellowship in Trieste, Italy, His research focuses on many diverse topics, from the emptiest regions of the universe to the earliest moments of the Big Bang to the hunt for the first stars. As an "Agent to the Stars," Paul has passionately engaged the public in science outreach for several years. He is the host of the popular "Ask a Spaceman!" podcast, author of "Your Place in the Universe" and "How to Die in Space" and he frequently appears on TV — including on The Weather Channel, for which he serves as Official Space Specialist.