A Star Just Ripped Comet Halley's Massive Cousin to Shreds

The cosmos is a harsh and unforgiving place, especially if you're a comet. Composed of rock and various volatiles, like water ice, these interplanetary vagabonds are formed during the genesis of star systems and may float, for billions of years, untouched and untroubled in a distant orbit around their parent stars. But then, through some unfortunate series of events, a passing star may disrupt a star's so-called Oort Cloud or Kuiper Belt, and these frozen bodies will drop on a path to eventual stellar doom.

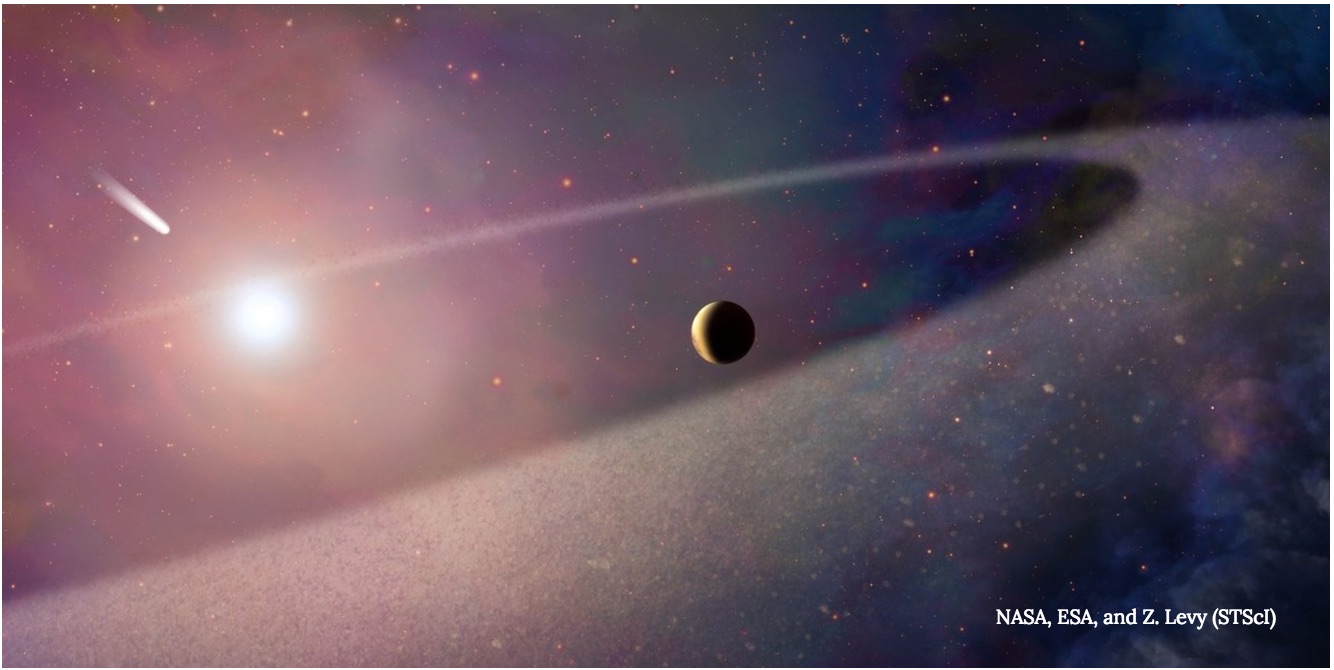

And for a huge comet orbiting a white dwarf star some 170 light-years away, that doom has arrived in dramatic fashion.

While surveying the chemical makeup of white dwarf stars, astronomers using the Hubble Space Telescope and W. M. Keck Observatory noticed something peculiar about WD 1425+540. The star, located in the constellation of Boötes, has a polluted atmosphere containing carbon, oxygen, sulfur and, strangely, nitrogen.

Spectroscopic analysis of the white dwarf's starlight revealed that a massive comet, with a similar chemical composition as the solar system's Halley's Comet, must have undergone the mother of tidal disruption events, ultimately getting ripped to shreds, spreading its debris throughout the star's atmosphere. But this comet was 100,000 times more massive than Halley and appeared to have twice the proportion of water.

RELATED: Caught in the Act: White Dwarf is Killing a Planet

Although other white dwarfs have been observed ripping up rocky debris like asteroids and planets in the past, this one is special — it's the first time comet debris containing nitrogen, an element essential for life, has been spotted polluting a white dwarf's atmosphere.

"Nitrogen is a very important element for life as we know it," said Siyi Xu, of the European Southern Observatory in Germany, in a statement. "This particular object is quite rich in nitrogen, more so than any object observed in our solar system."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

White dwarfs are the stellar remains of sun-like stars that have lived out their lives and died. Our sun, in another 4-5 billion years will run out of hydrogen fuel in its core and will start to fuse heavier elements. This will result in the sun puffing up into a huge red giant, swelling so wide that it will swallow Mercury and Venus, and possibly even Earth. Violent stellar winds will rip the outer layers apart, creating a vast planetary nebula. In the nebula's core will be a tiny, brightly shining clump of degenerate matter called a white dwarf — a star that's only the size of Earth, but 200,000 times more massive.

RELATED: Do Comets Rain Down on White Dwarf Stars?

As our white dwarf sun will be so small with an incredibly high density, it will possess strong tides — if a planet, asteroid or comet comes too close, these tides will literally rip any celestial body apart, sprinkling the debris over its upper layers, leaving a telltale spectroscopic signature showing that it used to have a planetary system in tow. And the fact that comets appear to be actively falling into WD 1425+540's atmosphere reveals the star system has a Kuiper Belt-like feature that survived the red giant phase of its star.

It's thought that the dynamical chaos inflicted on the star system after the star passed through the red giant phase knocked any planets in orbit off-kilter, causing gravitational instabilities that tugged the massive comet to fall into its star.

It's sobering to think that when we observe white dwarfs in our galaxy, we're basically looking into the future, seeing what our solar system will look like when our sun eventually dies.

WATCH VIDEO: Could Life on Earth Have Come From a Comet?

Originally published on Seeker.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.