Life's Building Blocks Found on Dwarf Planet Ceres

The dwarf planet Ceres keeps looking better and better as a possible home for alien life.

NASA's Dawn spacecraft has spotted organic molecules — the carbon-containing building blocks of life as we know it — on Ceres for the first time, a study published today (Feb. 16) in the journal Science reports.

And these organics appear to be native, likely forming on Ceres rather than arriving via asteroid or comet strikes, study team members said. [Photos: Dwarf Planet Ceres, the Solar System's Largest Asteroid]

"Because Ceres is a dwarf planet that may still preserve internal heat from its formation period and may even contain a subsurface ocean, this opens the possibility that primitive life could have developed on Ceres itself," Michael Küppers, a planetary scientist based at the European Space Astronomy Centre just outside Madrid, said in an accompanying "News and Views" article in the same issue of Science.

"It joins Mars and several satellites of the giant planets in the list of locations in the solar system that may harbor life," added Küppers, who was not involved in the organics discovery.

Ceres finds keep rolling in

The $467 million Dawn mission launched in September 2007 to study Vesta and Ceres, the two largest objects in the main asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter.

Dawn circled the 330-mile-wide (530 kilometers) Vesta from July 2011 through September 2012, when it departed for Ceres, which is 590 miles (950 km) across. Dawn arrived at the dwarf planet in March 2015, becoming the first spacecraft ever to orbit two different bodies beyond the Earth-moon system.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

During its time at Ceres, Dawn has found bizarre bright spots on crater floors, discovered a likely ice volcano 2.5 miles (4 km) tall and helped scientists determine that water ice is common just beneath the surface, especially near the dwarf planet's poles.

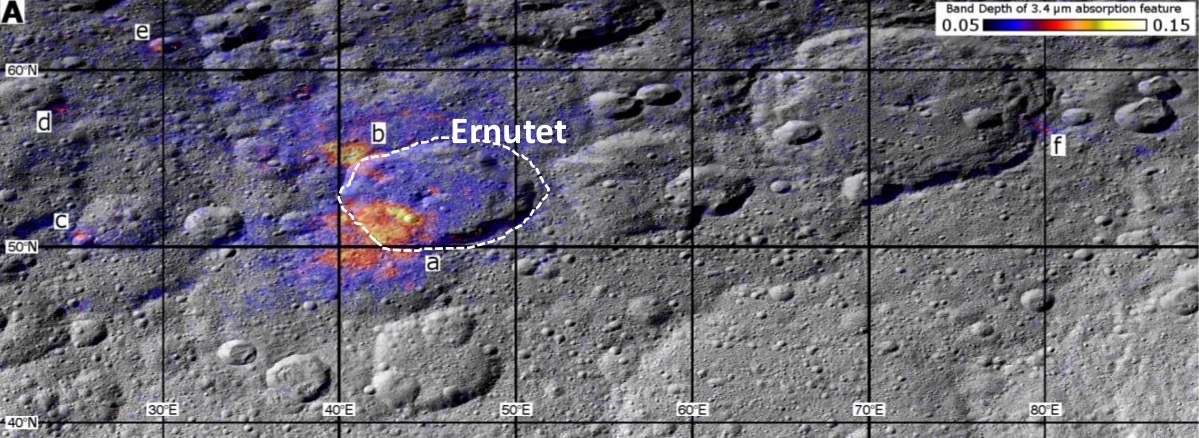

The newly announced organics discovery adds to this list of achievements. The carbon-containing molecules — which Dawn spotted using its visible and infrared mapping spectrometer instrument — are concentrated in a 385-square-mile (1,000 square km) area near Ceres' 33-mile-wide (53 km) Ernutet crater, though there's also a much smaller patch about 250 miles (400 km) away, in a crater called Inamahari.

And there could be more such areas; the team surveyed only Ceres' middle latitudes, between 60 degrees north and 60 degrees south.

"We cannot exclude that there are other locations rich in organics not sampled by the survey, or below the detection limit," study lead author Maria Cristina De Sanctis, of the Institute for Space Astrophysics and Space Planetology in Rome, told Space.com via email.

Dawn's measurements aren't precise enough to nail down exactly what the newfound organics are, but their signatures are consistent with tar-like substances such as kerite and asphaltite, study team members said.

Organics probably native

"The organic-rich areas include carbonate and ammoniated species, which are clearly Ceres' endogenous material, making it unlikely that the organics arrived via an external impactor," co-author Simone Marchi, a senior research scientist at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said in a statement.

In addition, the intense heat generated by an asteroid or comet strike likely would have destroyed the organics, further suggesting that the molecules are native to Ceres, study team members said.

The organics might have formed via reactions involving hot water, De Sanctis and her colleagues said. Indeed, "Ceres shows clear signatures of pervasive hydrothermal activity and aqueous alteration," they wrote in the new study.

Such activity likely would have taken place underground. Dawn mission scientists aren't sure yet how organics generated in the interior could make it up to the surface and leave the signatures observed by the spacecraft.

"The geological and morphological settings of Ernutet are still under investigation with the high-resolution data acquired in the last months, and we do not have a definitive answer for why Ernutet is so special," De Sanctis said.

It's already clear, however, that Ceres is a complex and intriguing world — one that astrobiologists are getting more and more excited about.

"In some ways, it is very similar to Europa and Enceladus," De Sanctis said, referring to ocean-harboring moons of Jupiter and Saturn, respectively.

"We see compounds on the surface of Ceres like the ones detected in the plume of Enceladus," she added. "Ceres' surface can be considered warmer with respect to the Saturnian and Jovian satellites, due to [its] distance from the sun. However, we do not have evidence of a subsurface ocean now on Ceres, but there are hints of subsurface recent fluids."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.