Searching for Life on 7 Nearby Alien Worlds: How Scientists Will Do It

The hunt for signs of life on seven nearby exoplanets will likely begin just a few years from now.

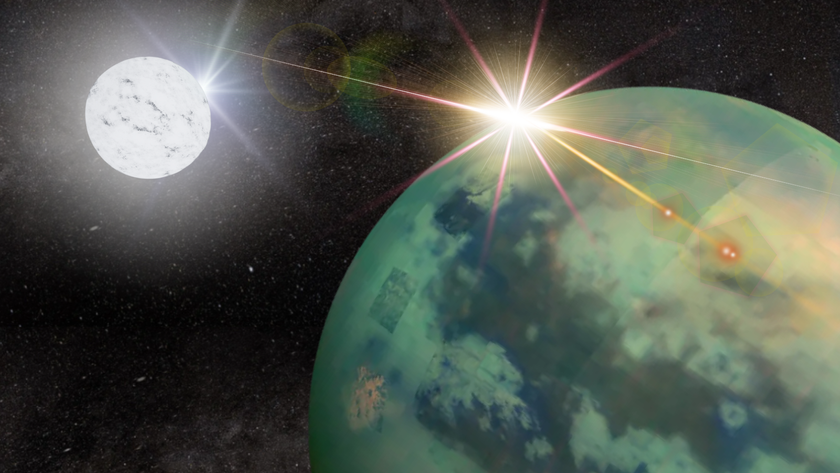

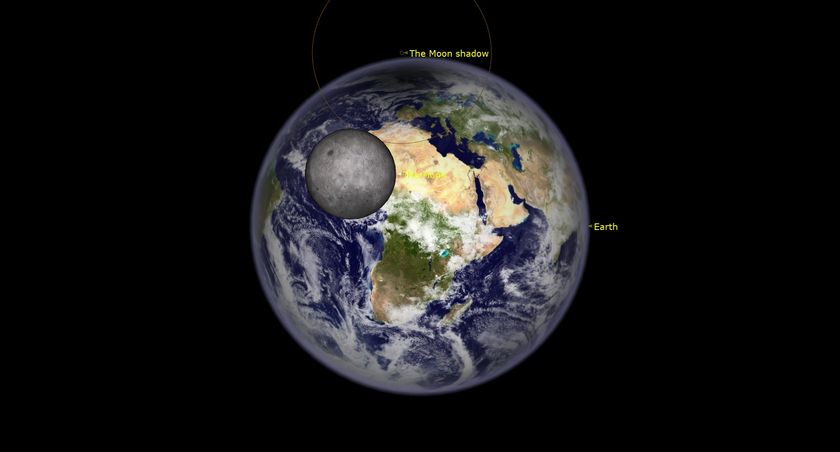

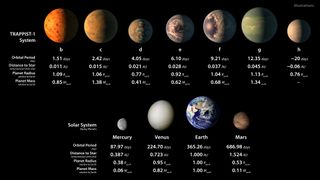

An international research team announced today (Feb. 22) that seven roughly Earth-size alien worlds orbit the small, dim star TRAPPIST-1, which lies just 39 light-years from Earth. (For perspective: Our Milky Way galaxy is 100,000 light-years wide. The closest star to the sun, Proxima Centauri, is about 4.2 light-years away.)

Three of these planets appear to be in TRAPPIST-1's "habitable zone," the range of distances where liquid water (and, by extension, life as we know it) could potentially exist on a world's surface. And all seven may be capable of harboring water, given certain atmospheric conditions, study team members said. [Images: The 7 Earth-Size Worlds of TRAPPIST-1]

This combination of proximity and potential habitability makes TRAPPIST-1 an inviting target in the search for E.T.

"Looking for life elsewhere, this system is probably our best bet as of today," study co-author Brice-Olivier Demory, a professor at the Center for Space and Habitability at the University of Bern in Switzerland, said in a statement.

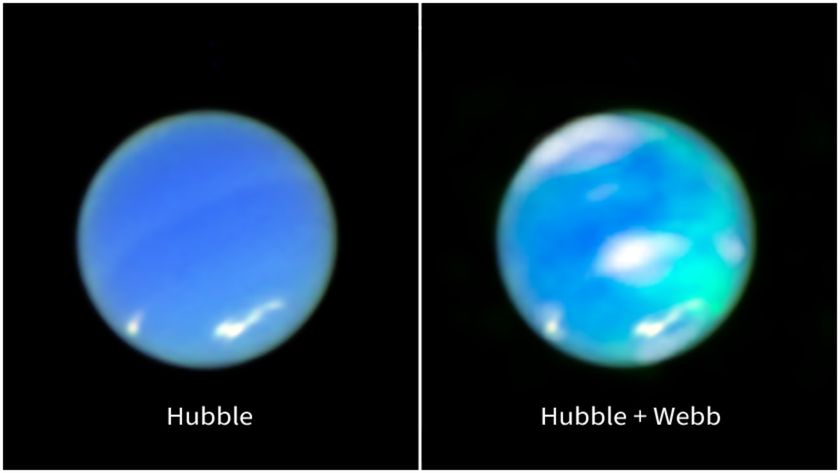

The team continues to study the TRAPPIST-1 system with Hubble. But such work can characterize atmospheres only in a relatively broad sense; the hunt for possible signatures of life such as oxygen and methane will require new instruments, the researchers said.

Luckily, such gear will be online soon. NASA's $8.8 billion James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is scheduled to launch in late 2018, and three huge ground-based instruments — the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT), the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT) and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT) — should start observing the heavens by the early to mid-2020s.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Indeed, the TRAPPIST-1 system will likely be one of the first targets for JWST once the telescope is operational, Nikole Lewis, an astronomer at the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore and co-leader of the 2016 Hubble study, said during a press briefing today. JWST's observations should allow astronomers to get a good handle on the TRAPPIST-1 planets' atmospheres by the early 2020s, Lewis added.

JWST, E-ELT, GMT and TMT will all be capable of sniffing out "biosignature" gases, their builders have said. (The big ground-based scopes will also be able to image a number of exoplanets directly, but the TRAPPIST-1 worlds aren't good candidates for such photography because they're so close to their parent star, study team members said.)

Detecting either oxygen or methane by itself in a planet's atmosphere wouldn't be compelling evidence of alien life, because both of these gases can be produced by abiotic as well as biotic processes, astronomers have stressed. Finding the two of them together, however, would be a different story.

"They destroy each other," Shawn Domagal-Goldman, a scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said in 2014 during a NASA panel discussion about ancient Earth and habitable exoplanets. "If they're both there together, you know someone is bringing the methane in an atmosphere rich in oxygen, so that's what you're looking for. The most likely explanation is, it's life that's bringing the methane and oxygen to the party."

So astronomers will likely search for methane, oxygen and other gas combos in the skies of the TRAPPIST-1 worlds when JWST and the big ground scopes become operational. But even success on this front would not necessarily provide universally accepted, slam-dunk evidence for life, said Michaël Gillon of the University of Liège in Belgium, leader of the new TRAPPIST-1 study.

"We will never be 100 percent sure until we go there, or get something," Gillon told reporters Tuesday (Feb. 21). (By "get something," he meant a signal from an alien civilization.)

A robotic probe won't be zooming through the TRAPPIST-1 system anytime soon, but this prospect is not out of the question. Last year, a team of scientists and engineers announced the $100 million Breakthrough Starshot project, which aims to develop the technology required to blast tiny, sail-equipped probes through space at up to 20 percent the speed of light using powerful lasers.

If Breakthrough Starshot pans out, such spacecraft could conceivably make it to the TRAPPIST-1 system about 200 years after lifting off.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.