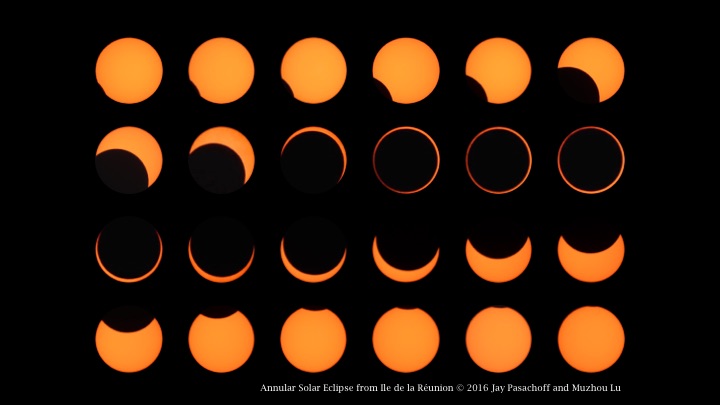

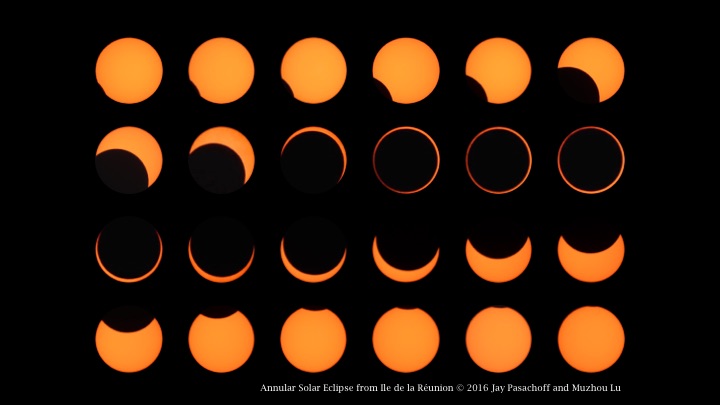

Scientists Practice Total Eclipse Science During Annular Solar Eclipse Sunday

Update for Sunday, Feb. 26: The "ring of fire" annular solar eclipse amazed observers across South America and Africa. See our full story here: Moon Blocks (Most of) the Sun in 'Ring of Fire' Solar Eclipse.

Sunday's annular eclipse will provide a practice run for scientists hoping to gather data during the fleeting moments of the total solar eclipse that will cross the U.S on Aug. 21.

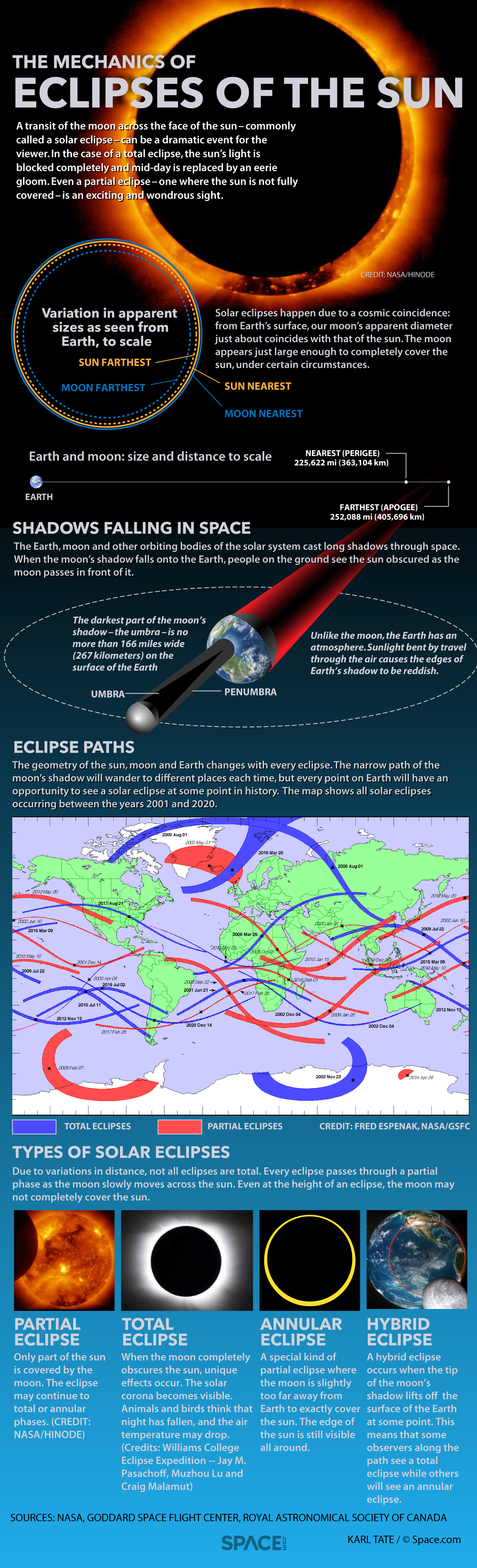

During the total solar eclipse that will take place in August, scientists positioned across the U.S. will be scrambling to gather data in the 2 minutes or so that the moon covers the entire disc of the sun. There is a wealth of science that can be done during an eclipse, including studying how the sudden darkening of the sky changes conditions on Earth (such as rapid drops in air temperature). A total eclipse also provides a totally unique view of the sun's outer atmosphere, called the corona.

Jay Pasachoff, a professor of astronomy at Williams College in Massachusetts, might be involved in more total-eclipse-related science investigations than anyone else on the planet (not even he can keep track of exactly how many, but this Space.com reporter counts at least seven). Tomorrow, he and some of his collaborators will be in southern Argentina, observing the annular solar eclipse — when about 99 percent of the sun will be covered by the moon — as a practice run for August's main event. [Total Solar Eclipse 2017: Path, Viewing Maps and Photo Guide]

Pasachoff said he figures people ask him to get involved with their solar eclipse experiments because he has a lot of experience observing them. He's personally been to 33 total solar eclipses, 15 partial eclipses and 16 annular eclipses (Sunday will be his 17th. Total solar eclipses happen about once every 18 months, but they are only visible over a relatively small area (as opposed to partial solar eclipses or lunar eclipses, which are usually visible across multiple continents).

In 2015, Pasachoff traveled to Svalbard, an island in the northern Norwegian archipelago, to see the total solar eclipse. While there, he and his colleague Marcos Peñaloza-Murillo, a research scientist at the University of the Andes in Venezuela, measured the temperature change that took place as the sun began to slip behind the moon. The temperature dropped from about 8 degrees Fahrenheit to minus 7 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 13 degrees to minus 21 degrees Celsius) in less than an hour, with a dramatic drop occurring immediately after the sun's disc became completely obscured.

The two colleagues are going to measure the temperature drop from Salem, Oregon, this summer, but the Sunday annular eclipse will serve as a practice run. Conducting experiments during totality can often involve making adjustments to equipment and jotting down notes. If something goes wrong with the data collection, it could be years before the opportunity comes along again.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"A lot of the reason for going to the annular eclipse is to get the routine down," Pasachoff said. "There's a lot of juggling, and practice helps. It helps us so we know we'll get it right in August."

Movies of the sun

One of the most massive undertakings that Pasachoff is involved with is called the Megamovie project, which will involve over 1,000 volunteers and many other citizen scientists in the path of totality. Volunteers across the country will capture footage of the sun when it is entirely obscured by the moon; these volunteers will use high-quality cameras and be trained on how to capture the sun. The footage will be stitched together to create a movie that tracks the view of the eclipse all the way across the country.

In addition, the Megamovie project will release an app that anyone can download on their smartphone and use to capture images or footage of the eclipse. That footage will be stitched together into a separate movie. Pasachoff said he and some colleagues will use the annular eclipse to test the Megamovie app.

That's not all Pasachoff will be doing this weekend. He'll also be working on something called the Modern Eddington Experiment.

"We are trying to recreate the observations that Arthur Eddington made of the eclipse in 1919 that verified Einstein's theory and made Einstein famous," he said.

During the 1919 eclipse, Eddington observed the light from background stars that would normally be invisible next to the sun's overwhelming glow. He demonstrated that the sun — a very massive object — could actually bend starlight around it; the effect is called gravitational lensing. It proved Albert Einstein's ideas about gravity being able to bend space, and turned him into a celebrity overnight. Pasachoff said the annular eclipse provides the opportunity to calibrate the experimental instruments to the changing temperatures and lighting conditions that are expected to occur during the total eclipse.

Pasachoff is also involved in outreach efforts, and he strongly encourages people to try and get into the path of totality in August. A total solar eclipse is a sight like none other — a sight so beautiful it has compelled so-called "eclipse chasers" like Pasachoff to travel all over the world to see them.

The path of totality for the August eclipse extends from Oregon to South Carolina. The duration of totality depends on how close an observer is to the center of the path of totality, so people standing near the edge of the path may only see this amazing sight for a few seconds. Even when 99 percent of the sun's disc is covered by the moon, the sky is still 10,000 times brighter than it is during totality, Pasachoff said.

"That's bright enough to hide very interesting phenomena," he said. "You really have to be within totality — and not even a few miles off to the side [of the path] — to really get the benefit of what we will be able to see on Aug. 21. I hereby appeal to people who think 90 percent or 99 percent coverage is enough. It's not good enough. You have to be within 100 percent."

Editor's note: You don't have to be traveling with Jay Pasachoff's solar eclipse team to see Sunday's annular solar eclipse. The online astronomy service Slooh.com will offer a free live webcast of the eclipse here, beginning at 7 a.m. EST (1200 GMT). You can also watch the webcast here, courtesy of Slooh. If you safely take a photo of the "ring of fire" eclipse that you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a possible story or image gallery, send images and comments to: spacephotos@space.com.

Editor's Note: This article previously stated that Pasachoff will be observing the total eclipse from Salem, Massachusetts; he will be watching it from of Salem, Oregon.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter