How to Use Your Phone or DSLR to Help Make an Eclipse 'Megamovie'

The University of California and Google want your help to make the longest movie ever of a total solar eclipse.

The university and the tech giant are seeking volunteers to make a "megamovie" that will not only document the Aug. 21, 2017, solar eclipse but could also help scientists discover new information about the sun's corona — the atmosphere above the solar surface, according to a statement from the University of California, Berkeley.

Hugh Hudson, a solar physicist at UC Berkeley, and Scott McIntosh, a scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research's High Altitude Observatory, proposed the "Eclipse Megamovie Project" idea in 2011, and now it's starting to take shape. [How to Safely Watch The 2017 Total Solar Eclipse]

"We'll be collecting this level of data for the first time, from millions of observers, and it will be a valuable archive," Hudson said.

The plan is to collect images from more than 1,000 volunteers with high-quality cameras and string them together into a 90-minute film. The Eclipse Megamovie project team will choose and train the core group of volunteers, but they'll also take contributions from anyone with a smartphone. The team says that, by April, it should have an app that takes time-coded pictures of the eclipse. The app will allow users to upload photos for another, lower-resolution film.

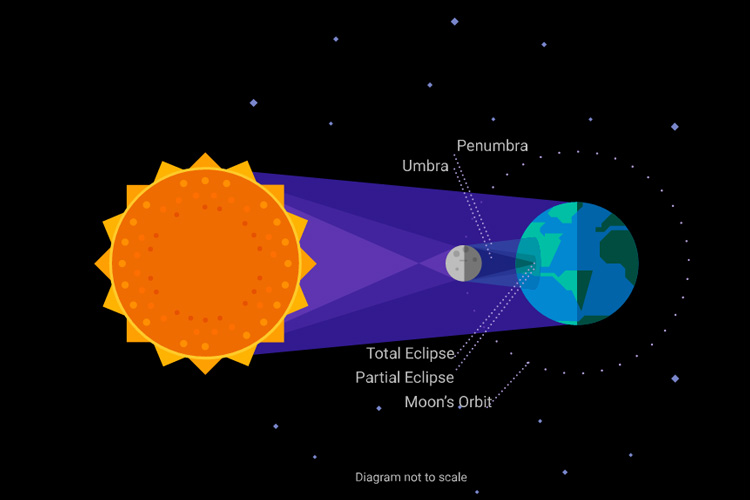

During totality, when the disk of the moon completely covers the disk of the sun, it's possible to see the sun's corona, which is usually invisible from the Earth's surface. Totality rarely lasts longer than a few minutes. The theoretical maximum is seven minutes and thirty seconds with most eclipses hitting the two to three minute mark. That puts a short time limit on scientific studies. Even airplanes that try to follow the moon's shadow as it travels can't keep up, since the shadow moves at some 1,500 mph (2,400 km/h).

Using an instrument called a coronagraph that blocks the disc of the sun, it's possible to see the corona — NASA currently has instruments in space that use coronagraphs to observe the sun's atmosphere. But even with coronagraphs, the light from the sun's lower atmosphere, called the chromosphere, is still lost in the glare, according to NASA. The moon, however, makes the chromosphere visible.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We don't know what we'll see or what we'll learn about the interactions between the chromosphere and the corona," Hudson said.

The movie may also help scientists study lunar geography. Just before the moon completely covers the sun, observers can see the sliver of light from the sun break up into spots of light that look like beads on a necklace — called Baily's beads — that show lunar topography, because the sun is shining through valleys or low points on the moon's surface. The beads reappear when the sun begins to emerge on the other side of the moon.

Another effect, called the "diamond ring," refers to the last bead of sunlight left before totality and the first one to appear afterward. This effect can reveal features and help refine estimates of the size of the sun, according to the statement.

The Astronomical Society of the Pacific is reaching out to its more than 400 amateur astronomy groups and encouraging them to participate in the project. The Megamovie team primarily comprises staff from UC Berkeley's Multiverse education program, who are contacting cities and towns along the path of totality, which runs from Oregon to South Carolina, to encourage participation in the project.

To contribute to the high-resolution megamovie, participants need a digital single-lens reflex camera, or DSLR, with a zoom lens of at least 300 millimeters, plus a tripod and the ability to record their GPS location and the local time to within 1 second in coordinated universal time (UTC), the world's clock standard.

The first version of the eclipse megamovie should be ready online a few hours after the eclipse ends at 1:49 p.m. EDT (1749 GMT).

To learn more about the Eclipse Megamovie Project, or participate, visit the project's website here: http://eclipsemega.movie/.

Follow Jesse Emspak on Twitter @Mad_Science_Guy. You can follow us @Spacedotcom and on Facebook & Google+. Original story on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Jesse Emspak is a freelance journalist who has contributed to several publications, including Space.com, Scientific American, New Scientist, Smithsonian.com and Undark. He focuses on physics and cool technologies but has been known to write about the odder stories of human health and science as it relates to culture. Jesse has a Master of Arts from the University of California, Berkeley School of Journalism, and a Bachelor of Arts from the University of Rochester. Jesse spent years covering finance and cut his teeth at local newspapers, working local politics and police beats. Jesse likes to stay active and holds a fourth degree black belt in Karate, which just means he now knows how much he has to learn and the importance of good teaching.

Most Popular