Tiny Asteroid Zips By Earth, Won't Be Back for More Than 100 Years

An asteroid less than 10 feet (3 meters) across buzzed Earth last week, diving in closer than many communications and weather satellites.

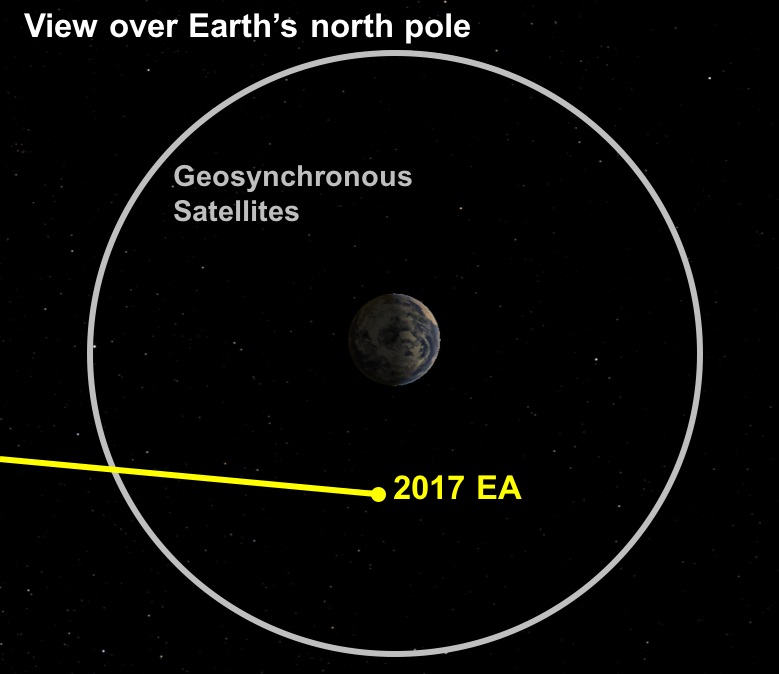

The asteroid, called 2017 EA, passed closest to Earth on Thursday, March 2, at 9:04 a.m. EST (1404 GMT) above the eastern Pacific Ocean. It reached within 9,000 miles (14,500 kilometers) of Earth, which is less than one-twentieth the distance from Earth to the moon, officials from NASA's Center for Near-Earth Object Studies (CNEOS) said in a statement. It won't be back in Earth's neighborhood for more than 100 years, they added.

Researchers monitoring the Catalina Sky Survey in Arizona first spotted the asteroid 6 hours before its closest approach; many other observatories monitored it as well as it flew toward Earth. It disappeared from view into Earth's shadow just before its nearest point.

The asteroid came in closer than satellites in geosynchronous orbit — the farthest orbit satellites regularly use, where they stay over one part of Earth as it turns. That orbit is good for providing communication services or monitoring one particular part of Earth's surface.

Space.com asked asteroid researcher Carrie Nugent, at IPAC, NASA's science and data center at California Institute of Technology, what would have happened had 2017 EA hit Earth rather than just passing by.

"I would imagine 3 meters wouldn't be much of a worry," said Nugent, who is the author of an upcoming book on asteroid monitoring called "Asteroid Hunters" (TED Books, 2017).

"It would likely burn up very quickly, it might create a beautiful light show, maybe you might have some meteorites out of it — but maybe not." The exact effect would depend on the asteroid's composition, she added; predicting an asteroid's effects based on its composition is an active area of study.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Although the asteroid was a stranger as it came in, its oblong orbit around the sun is now well understood as it heads back out. And researchers won't get another close look for more than 100 years.

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.