Old Stardust in Young Galaxy Sheds Light on the First Stars

Astronomers have spotted a young galaxy far, far away that is loaded with ancient stardust from some of the earliest stars in the universe.

The dusty galaxy, named A2744_YD4, is the youngest and most remote galaxy ever observed by the European Southern Observatory's Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile. You see a video of A2744_YD4 here by ESO scientists.

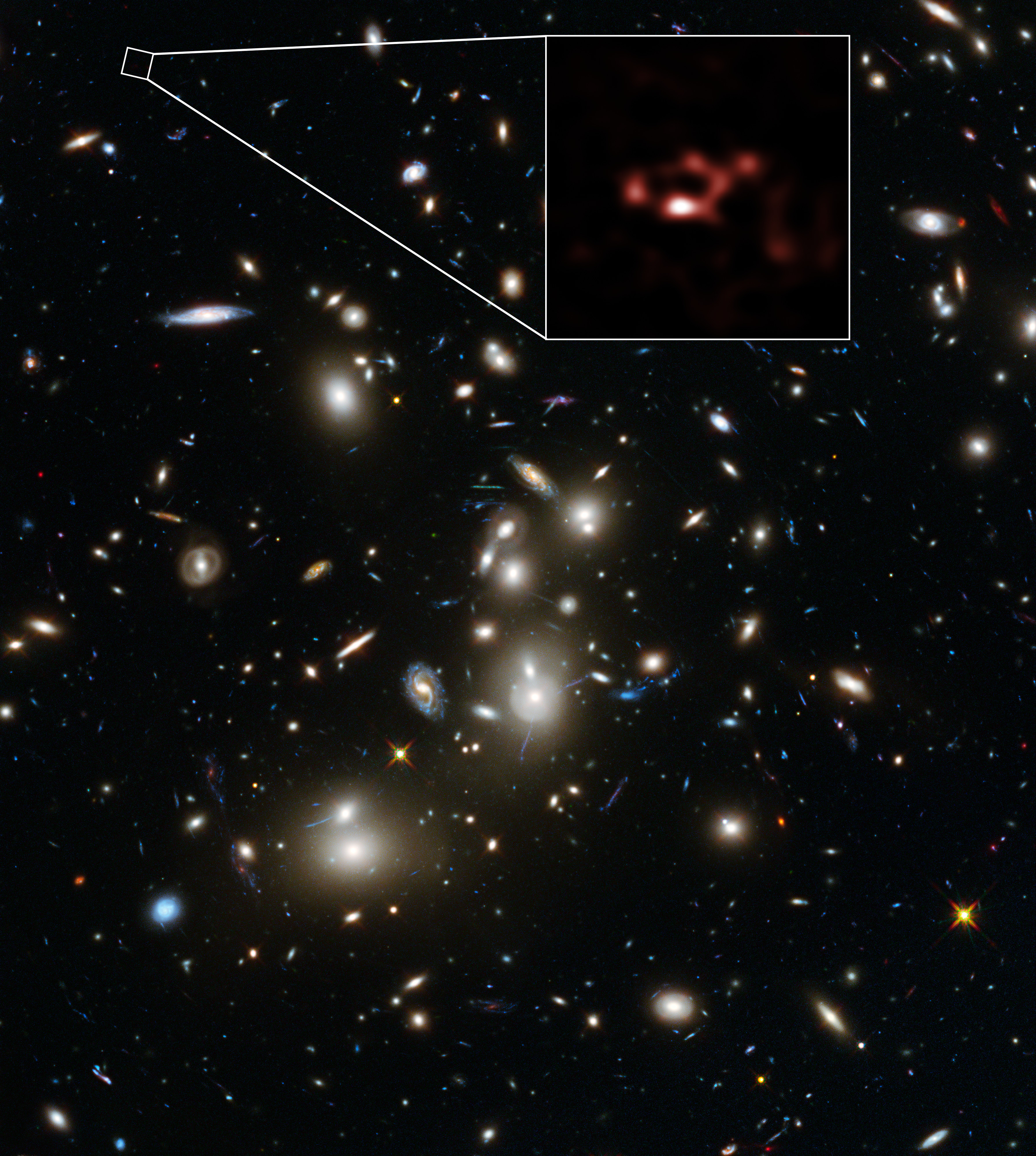

A2744_YD4 resides some 13 billion light-years away from Earth in the constellation Sculptor, behind a group of galaxies known as Pandora's Cluster. All of the gravity around Pandora's Cluster helped astronomers see A2744_YD4 by magnifying the light, a process known as gravitational lensing.

Because the newfound galaxy is so far away, astronomers see it the way it looked when the universe was only 600 million years old. Scientists estimate that the universe is about 13.8 billion years old, so light from A2744_YD4 has spent just about an eternity traveling to the ALMA telescope array.

To confirm this distance, astronomers turned to a spectrograph instrument on ESO's Very Large Telescope known as X-shooter. This tool analyzes the light coming from stars to determine properties like size and composition.

"Not only is A2744_YD4 the most distant galaxy yet observed by ALMA, but the detection of so much dust indicates [that] early supernovae must have already polluted this galaxy," lead researcher Nicolas Laporte, of University College London, said in a statement.

When stars die in supernova explosions, they leave behind clouds of dust and gas that can later form new stars, planets and other celestial bodies. So when astronomers found these old star remnants inside one of the youngest galaxies ever seen, the discovery came as a surprise. In the earliest days of the universe, when the first generations of stars had not yet exploded, there wasn't much stardust around yet.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"The detection of dust in the early universe provides new information on when the first supernovae exploded and hence the time when the first hot stars bathed the universe in light," ESO officials said in a statement. "Determining the timing of this 'cosmic dawn' is one of the holy grails of modern astronomy, and it can be indirectly probed through the study of early interstellar dust."

Galaxy A2744_YD4 appears to hold enough of this stardust to make 6 million suns, while the mass of the galaxy's stars add up to 2 billion times the mass of the sun. Baby stars in A2744_YD4 are popping up at a rate of 20 solar masses per year, which is 20 times faster than the current rate of star formation in the Milky Way.

"This rate is not unusual for such a distant galaxy, but it does shed light on how quickly the dust in A2744_YD4 formed," study co-author Richard Ellis, of ESO and University College London, said in the statement. "Remarkably, the required time is only about 200 million years — so we are witnessing this galaxy shortly after its formation."

That means stars began to form 200 million years before the light from A2744_YD4 reached ALMA's telescope array, making the stardust that astronomers can see the remnants of some of the earliest stars in the universe, the researchers said.

"With ALMA, the prospects for performing deeper and more extensive observations of similar galaxies at these early times are very promising," Ellis said.

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.