What Cassini's Daring Ring-Dive Around Saturn Could Tell Us About Uranus

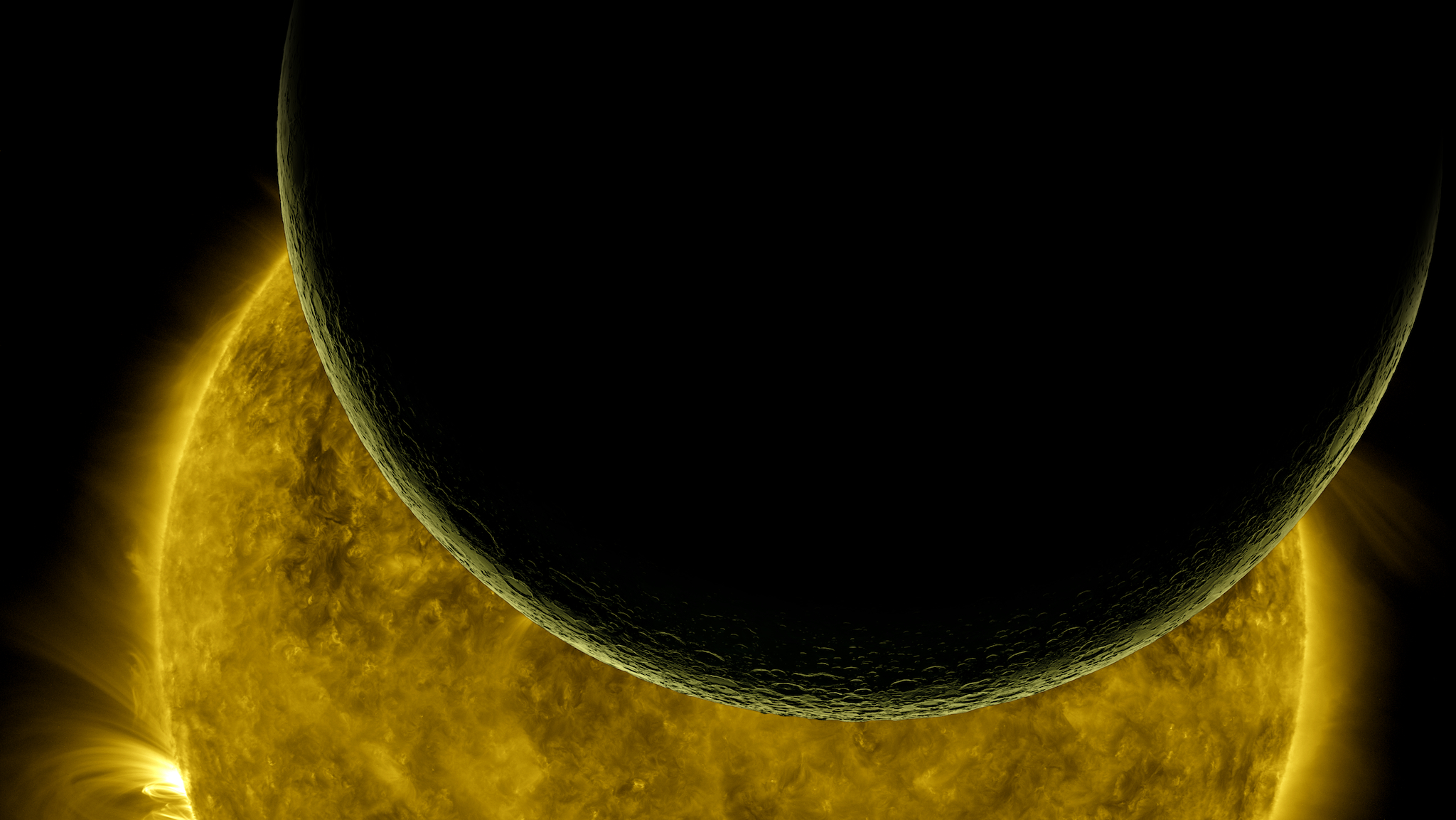

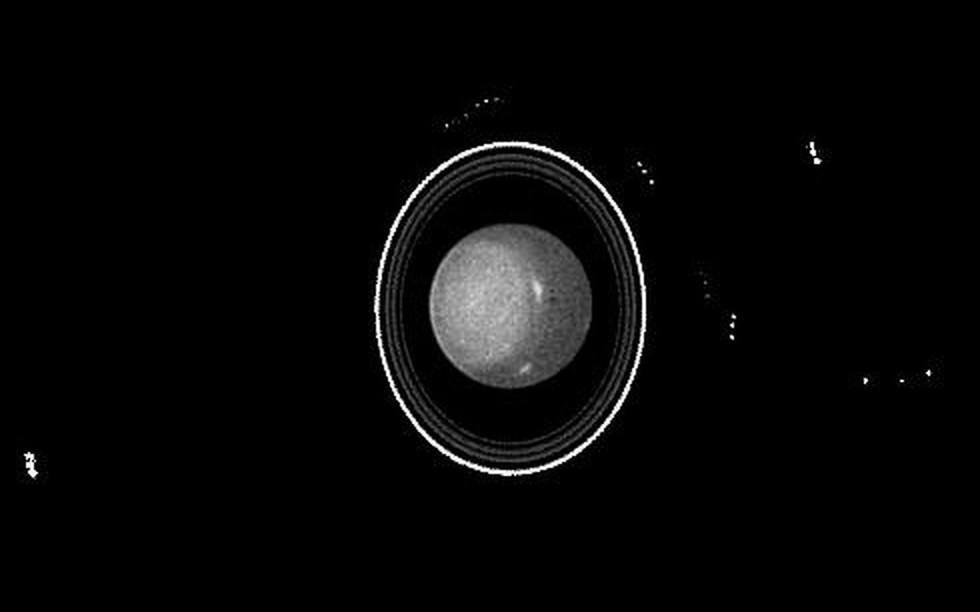

Glowing in pale blue, Uranus looks like a ghostly planet in pictures taken from the only spacecraft to ever visit it: Voyager 2. Due to the planet's great distance from Earth, follow-up studies of the planet began only in the late 1990s when telescope optics improved. Since then, Uranus has remained a low priority for observational institutions.

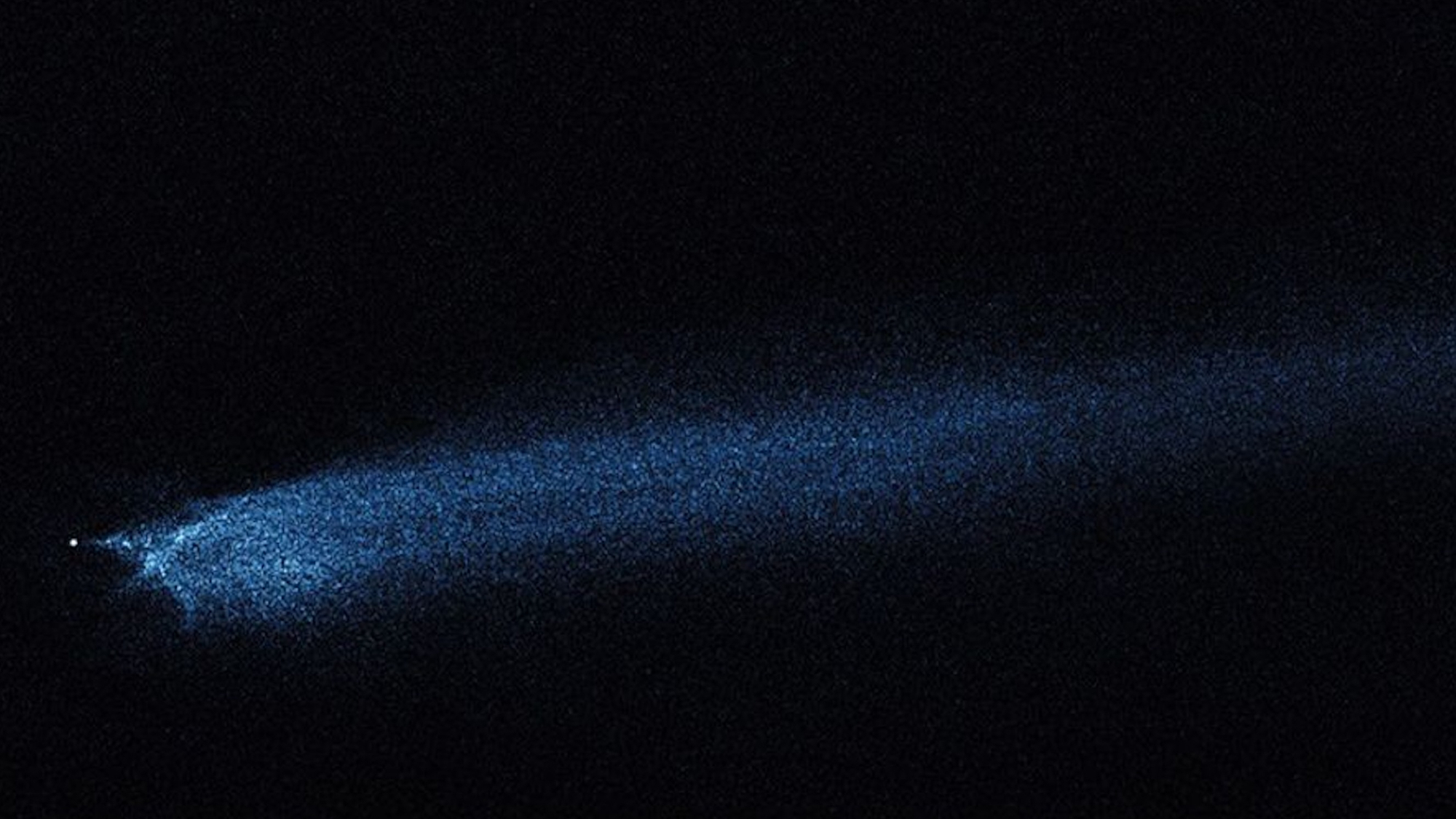

That's unfortunate for scientists looking to learn more about the faint rings of Uranus, discovered 40 years ago this year. Two airborne campaigns were set up to watch Uranus pass in front of a star in 1977. And both were taken aback when they found rings circling the planet. One of the teams missed three of the rings because they were so surprised by the find.

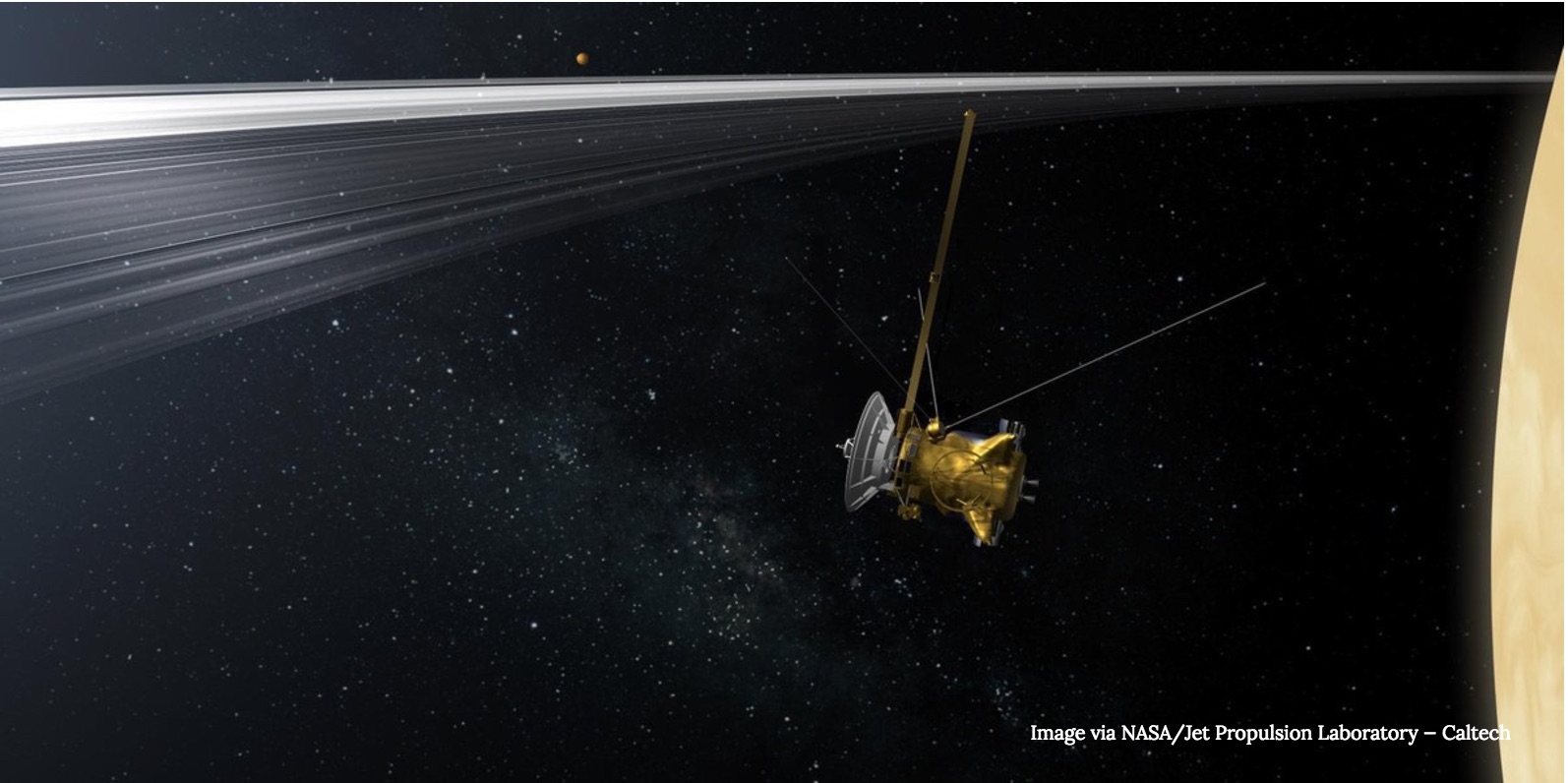

There are hopes that a spacecraft will fly to Uranus or Neptune in the 2020s or 2030s. NASA is undertaking early-stage feasibility studies. So it will remain to the plucky Cassini spacecraft, in orbit around Saturn since 2004, to show scientists what it can about the rings of Uranus by analogy with Saturn.

"At the time of the Uranian discovery, we had never seen narrow, dense rings before," said Mark Showalter, a planetary astronomer at the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence Institute. "The narrow rings of Saturn behave similarly to the rings of Uranus," he added, "so that has enabled us to understand dense rings a little bit better."

Cassini is in the final year of its epic mission, and is taking a rare close look at Saturn's rings in the coming weeks. The spacecraft is in the midst of performing 20 "ring-grazing orbits" that will allow for the best views of them since Cassini's arrival in 2004. The maneuvers began in November and run through April.

"[W]e expect to see the rings, along with the small moons and other structures embedded in them, as never before," Linda Spilker, Cassini project scientist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said in a statement. "The last time we got this close to the rings was during arrival at Saturn in 2004, and we saw only their backlit side. Now we have dozens of opportunities to examine their structure at extremely high resolution on both sides."

Following completion of the ring orbits, Cassini will perform unprecedented dives between Saturn and its rings between April and September. Then, on September 15, Cassini will make a suicidal plunge into Saturn itself to protect icy worlds like Enceladus from the small chance of Cassini crashing into and contaminating their surfaces.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But before that, Showalter points out, Cassini will provide more insights on what is happening within the Uranus system, even though the spacecraft is surveying a completely different planet. The wobbles in Saturn's narrow rings appear to move in similar ways that Uranian rings do, for example.

But there are still several mysteries that may take another Uranian mission to resolve.

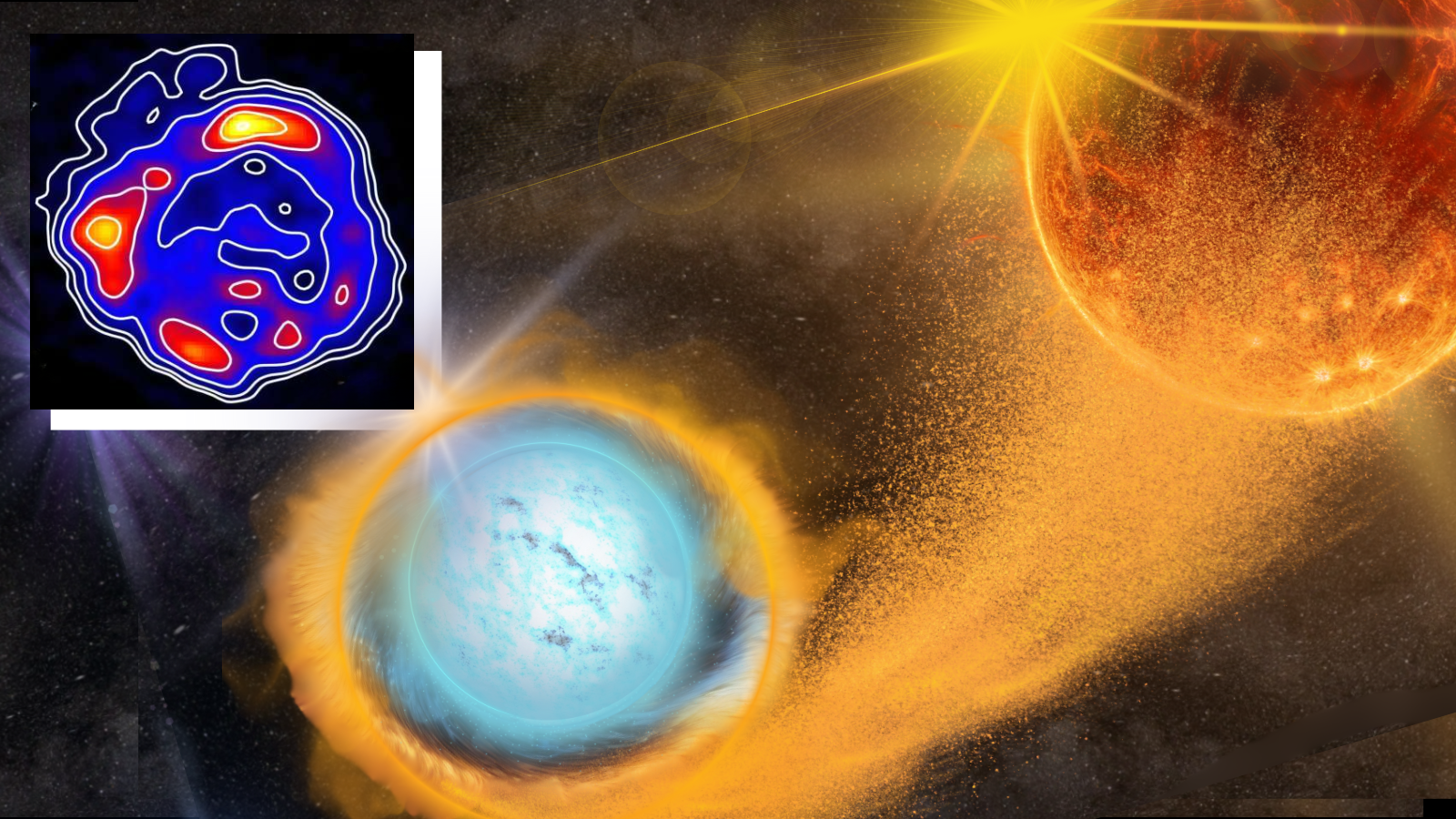

For example, images from Voyager 2 depicted dust rings surrounding the main ring system of. Then, when Uranus reached its equinox (closest point in its orbit) in 2008, observations from the Keck Telescope imaged the rings when they were edge-on from Earth, making it easier to identify the presence of any dust. It appears that the dust has shifted 3,100 miles between the two observations, Showalter said. The reason for the shift remains poorly understood.

RELATED: Risks on Mars Mean Humans Might Want to Follow Opportunity Rover's Tracks

Another open question is the role that the moons Cornelia and Ophelia play in shepherding the outer ring of Uranus — a phenomena also seen around Saturn. But the rings around Uranus are more difficult to observe right now because the planet is in an area of the sky with fewer stars, Showalter said, meaning the planet remains obscure more than it did in the 1970s and 1980s.

Showalter has been very busy in the past few years working on both the New Horizons mission, which passed by Pluto in 2015, as well as Cassini. He says he hopes to pull out some older data on Uranus soon to learn more about the planet's ring system, and to provide some insight for whenever a spacecraft does visit the Blue World again.

Originally published on Seeker.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.