Carbon Dioxide Is Warming the Planet (Here's How)

The head of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) said he does not believe that carbon dioxide is a main driver of climate change.

"I think that measuring with precision human activity on the climate is something very challenging to do, and there's tremendous disagreement about the degree of impact. So no, I would not agree that it's a primary contributor to the global warming that we see," EPA chief Scott Pruitt told CNBC's morning news show "Squawk Box" yesterday (March 9).

Pruitt's comments are in opposition to the scientific research on climate change. But when even the head of the EPA doubts the consensus, it can be hard to cut through the noise to understand what research scientists are really using when they express climate-change concern. [The Reality of Climate Change: 10 Myths Busted]

"I think plenty of people have pretty serious concerns in their life and they just don't have the time to do all of the homework and the background to figure this out," said Katherine Moore Powell, a climate ecologist at the Field Museum in Chicago.

So here's a primer explaining exactly why scientists know the climate is changing and that human activities are causing it.

Earth is warming

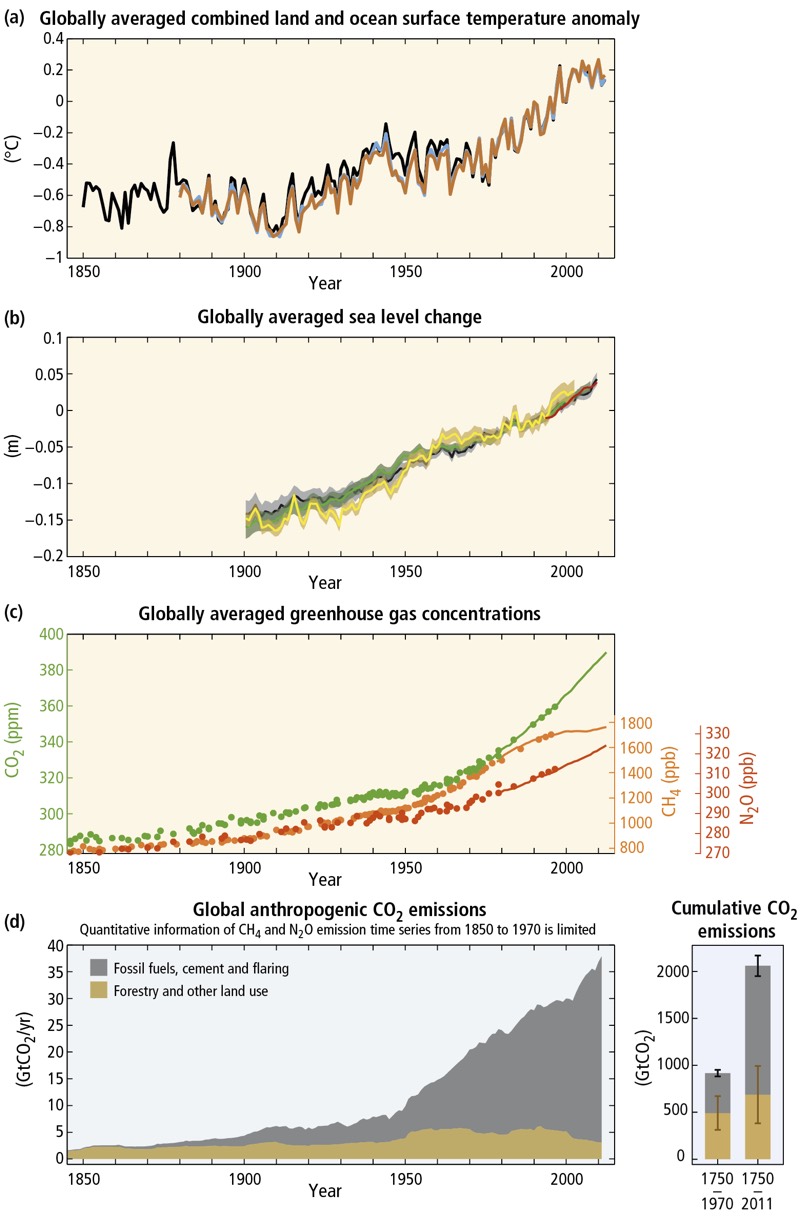

At this point, even the staunchest climate deniers would be hard-pressed to argue that the climate is not warming. Simply put, it's getting hotter out there. Combining land and ocean measurements from 1850 to 2012, researchers have found that the average surface-air temperature globally has risen by 1.4 degrees Fahrenheit (0.8 degrees Celsius) since the beginning of the industrial age. That's according to the fifth report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), released in 2014. The top graph in the figure from the IPCC report summary for policy makers shows the temperature anomaly in Celsius.

The next graph in this sequence shows sea-level rise, which has gone up globally by about 7.4 inches (0.19 meters) on average since 1901. According to the IPCC, the rate of sea-level rise since the middle of the 1800s has been higher than the rate during the previous two millennia. Scientists use tide gauges and satellite measurements to track sea-level changes, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Geologists and other Earth scientists can study rocks, fossils and sediment cores to get a longer-term look at sea-level changes, according to NASA.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The bottom two graphs show rising greenhouse-gas concentrations and estimated emissions of carbon dioxide by humans since 1850. The rising trend is evident on each figure. Scientists monitor carbon dioxide in the atmosphere by pumping air into an artificial chamberand shining an infrared light through the sample. Carbon dioxide absorbs infrared light very efficiently — more on that in a minute — so the amount of infrared absorbed can be used to calculate the amount of CO2 in the sample. [Top 10 Ways to Destroy Earth]

The premier (and longest-standing) site for these measurements is the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, which recently reported that the planet's atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration has surpassed 400 parts per million. In 1958, when observations at Mauna Loa began, the annual carbon dioxide concentration in the atmosphere was 315 parts per million.

The physics of greenhouse gases

Carbon dioxide is no dark-horse candidate for the warming of the atmosphere. In 1896, Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius (who would later win the first-ever Nobel Prize for Chemistry) published a paper in the Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science that laid out the basics of what's now known as "the greenhouse effect."

The effect is a result of how energy interacts with the atmosphere. Sunlight enters the atmosphere as ultraviolet and visible light; some of this solar energy is then radiated back toward space as infrared energy, or heat. The atmosphere is 78 percent nitrogen and 21 percent oxygen, which are both gases made up of molecules containing two atoms. These tightly bound pairs don't absorb much heat.

But the greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide, water vapor and methane, each have at least three atoms in their molecules. These loosely bound structures are efficient absorbers of the long-wave radiation (also known as heat) bouncing back from the planet's surface. When the molecules in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases re-emit this long-wave radiation back toward Earth's surface, the result is warming.

Is it really carbon dioxide?

So, temperatures are rising, as are levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. But are the two connected?

Yes. The evidence is strong. In 2006, scientists presented a poster at the 18th Conference on Climate Variability and Change that even measured the effect directly. Using spectrometers (tools that measure spectra to identify particular wavelengths), the researchers analyzed the wavelengths of infrared radiation reaching the ground. Based on the varying wavelengths, the scientists determined that more radiation was occurring due to the contribution of specific greenhouse gases.

Overall, they found that greenhouse gas radiation had increased by 3.5 watts per square meter compared with preindustrial times, a rise of just over 2 percent. Other researchers have noted "missing" infrared wavelengths in radiation into space, a phenomenon that happens because these missing wavelengths get stuck in the atmosphere.

Scientists also know that the extra carbon in the atmosphere is the very same carbon that comes from burning fossil fuels. By analyzing molecular variations called isotopes, researchers can trace the origin of atmospheric carbon, Moore Powell said.

"We know what the burning of fossil fuels looks like, in a scientific sense," she said.

That's not to say that the climate is as simple as an actual greenhouse. Many factors influence global temperatures, including volcanic eruptions and variations in the solar cycle and Earth's orbit that alter the amount of sunlight reaching the planet.

But scientists know that volcanoes and the sun aren't to blame for recent climate change. According to the IPCC, volcanic carbon dioxide emissions have been, at most, a hundredth of human CO2 emissions since 1750. In addition, volcanic eruptions cause changes for short timescales of about two years, not the longer-term changes being observed currently.

The sun is more complex, but researchers have found that the recent solar-cycle minimum (between 1986 and 2008) was actually lower than the previous two solar-cycle minimums (the sun moves between quiet minimums and active maximums about once every five years). If anything, the IPPC concluded, recent solar activity should have resulted in cooling, not warming. Likewise, a 2012 study found that between 2005 and 2010, a period when solar activity was low, the Earth still absorbed 0.58 watts of excess energy per square meter, continuing to warm despite the lower level of solar energy going into the system.

Where's the real uncertainty?

Given the weight of the evidence, scientists have come to a consensus that climate change is happening, and that human greenhouse gas emissions are the primary cause.

So where are the real scientific debates?

There are still a lot of questions left about how fast climate change will happen and what the precise effects will be.

"What I would say is most uncertain is simply how quickly things are chaning," Moore Powell said. "I'm very interested in the pace."

One of the major unknowns is the ultimate influence of clouds on climate: Clouds are white, so they reflect sunlight back toward space, which could have a cooling effect. But clouds are also water vapor, which traps heat. And different types of clouds might have warming or cooling effects, so the precise role of clouds in the feedback loop of global warming remains difficult to untangle, scientists have said.

Another burning question is how high, and how quickly, the sea level will rise as warming sea waters expand and Antarctic and Arctic ice melts. The IPCC forecasted a rise of 20 to 38 inches (52 to 98 cm), assuming no efforts are made to curb greenhouse gas emissions.

That range is broad, largely because the dynamics of Antarctic ice sheets are not completely understood. If Antarctica's land-based glaciers slough off to the sea rapidly with a little bit of warming, that will be bad news for coastal communities, researchers have said. That's why scientists are watching closely right now as a rift is splitting the Larsen C ice shelf on the Weddell Sea. If the giant iceberg-calving event about to occur destabilizes the ice shelf, it could result in the rapid flow of the land-based glaciers behind it into the ocean. This type of rapid glacial flow already occurred nearby, when the Larsen B ice shelf crumbled in 2002.

For an ecologist like Moore Powell, there are also myriad questions to answer about how ecosystems will respond to a changing climate. If the pace is slow enough, plants and animals can adapt. But in many places, the change is happening very quickly, Moore Powell said.

"There's not enough time at this pace for natural adaptation to take over," she said.

Original article on Live Science.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Space.com sister site Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.