Sleepless in Space: Therapy Helps Astronauts Snooze

Sleeping isn't always easy. For astronauts working at the International Space Station (ISS), a lack of quality sleep could be catastrophic. To deal with the struggle of sleeping in space, astronauts use a non-medication therapy strategy called cognitive behavioral therapy, which focuses on getting rid of thoughts and behaviors that can keep people awake at night.

Before astronauts blast off toward the space station, psychiatrists with NASA's Behavioral Health and Performance team offer sleep cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) education. This provides the astronauts with a set of psychological tools to help deal with problems like insomnia, short sleep syndrome, jet lag and circadian desynchrony, or a disruption in the body's biological clock. The American College of Physicians also recommends CBT as the "first-line" treatment for people who suffer from insomnia on Earth.

Sleep CBT teaches people to recognize and moderate certain thoughts and behaviors that affect sleeping habits. Relaxation and mindfulness training helps to reduce or eliminate racing thoughts that can keep people awake at night. CBT also covers environmental conditions and sleep hygiene, or lifestyle habits that can affect sleep. [Sleeping in Space: How Astronauts Get a Good Night's Rest]

Sleepless in orbit

Because the ISS travels around the Earth every 92 minutes, people on board see 16 sunrises and sunsets every day. On Earth, people's bodies depend on a 24-hour cycle of daylight and nighttime to produce hormones, like melatonin and cortisol, that regulate sleep schedules at the right times. When the body's natural clock, or its circadian rhythm, is perturbed due to jet lag or spaceflight, CBT can help restore normal sleep patterns.

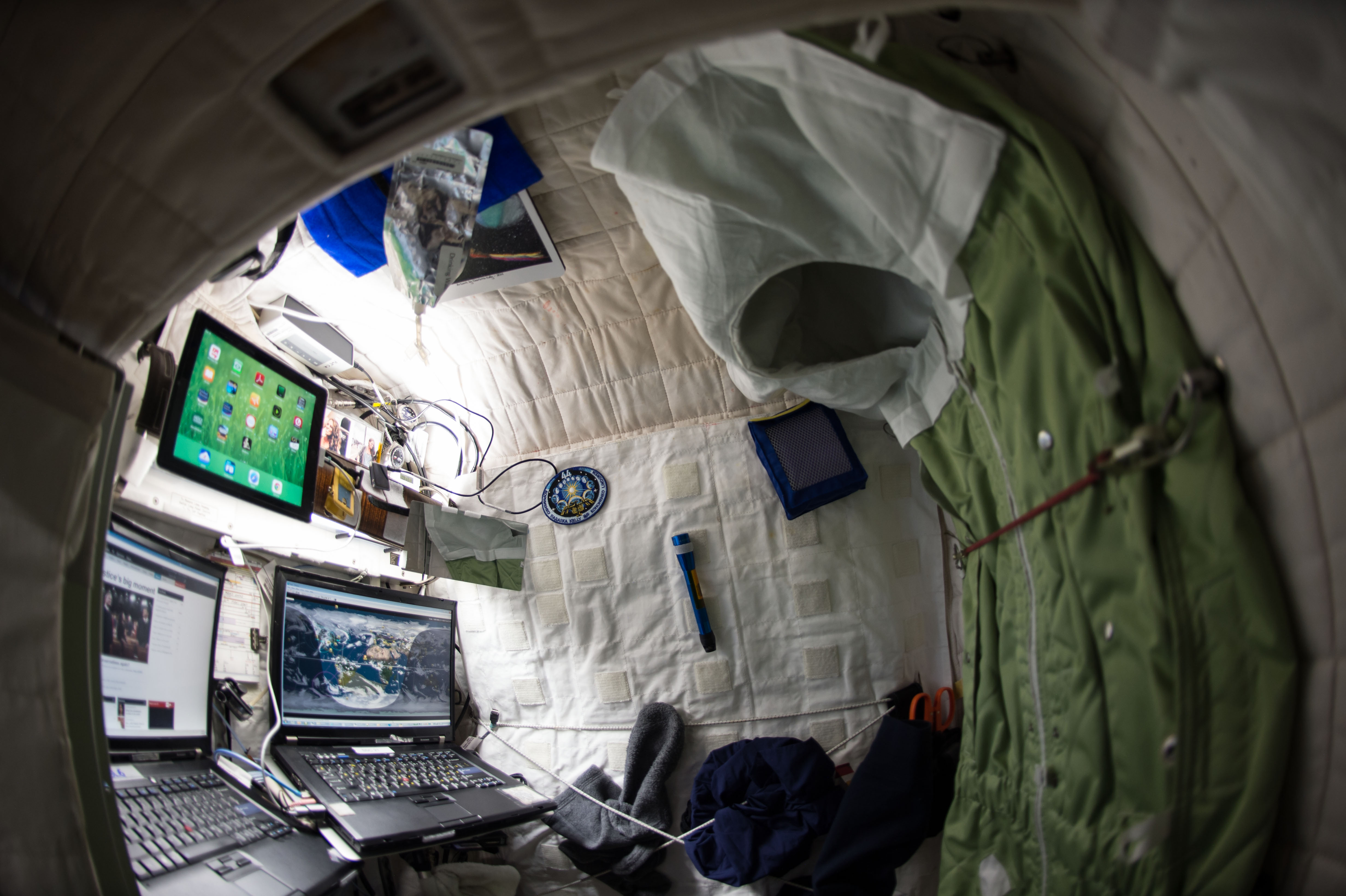

At the ISS, however, the unusual timing of daylight and darkness is one of many factors that can contribute to a lack of sleep. A demanding work schedule can also pose problems, particularly if spacecraft carrying cargo or other crewmembers arrive in the middle of the night.

"There are times when people just have insomnia," Ronald Moomaw, a NASA psychiatrist, told Space.com. "Usually, it's an anticipatory kind of event ... suppose you're doing your first EVA [spacewalk] and you've got something critically important to do." The excitement of anticipating that event might keep an astronaut lying (or floating) awake at night, Moomaw said.

Losing sleep the night before an EVA can be dangerous. Wearing a spacesuit while floating in microgravity may sound like a blast, but spacewalks are also physically demanding, NASA spokesperson Kelly Humphries told Space.com for a previous story. Usually, astronauts spend about 6 hours working outside the ISS with no breaks. Groggy, sleep-deprived minds could easily lead to mistakes like losing tools (or worse).

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Tips for sleeping in space (and on Earth)

Regardless of where you are, the basic components of sleep CBT are the same, Moomaw said. The major difference for astronauts is that they don't have the option of starting CBT during flight; they can either opt in to therapy during preflight training or go without it entirely.

"We don't have the ability to take the time out of their work schedule to put that type of training in," Moomaw said. "Their work schedule is incredibly tight, so once they're on the station, that would not be an option."

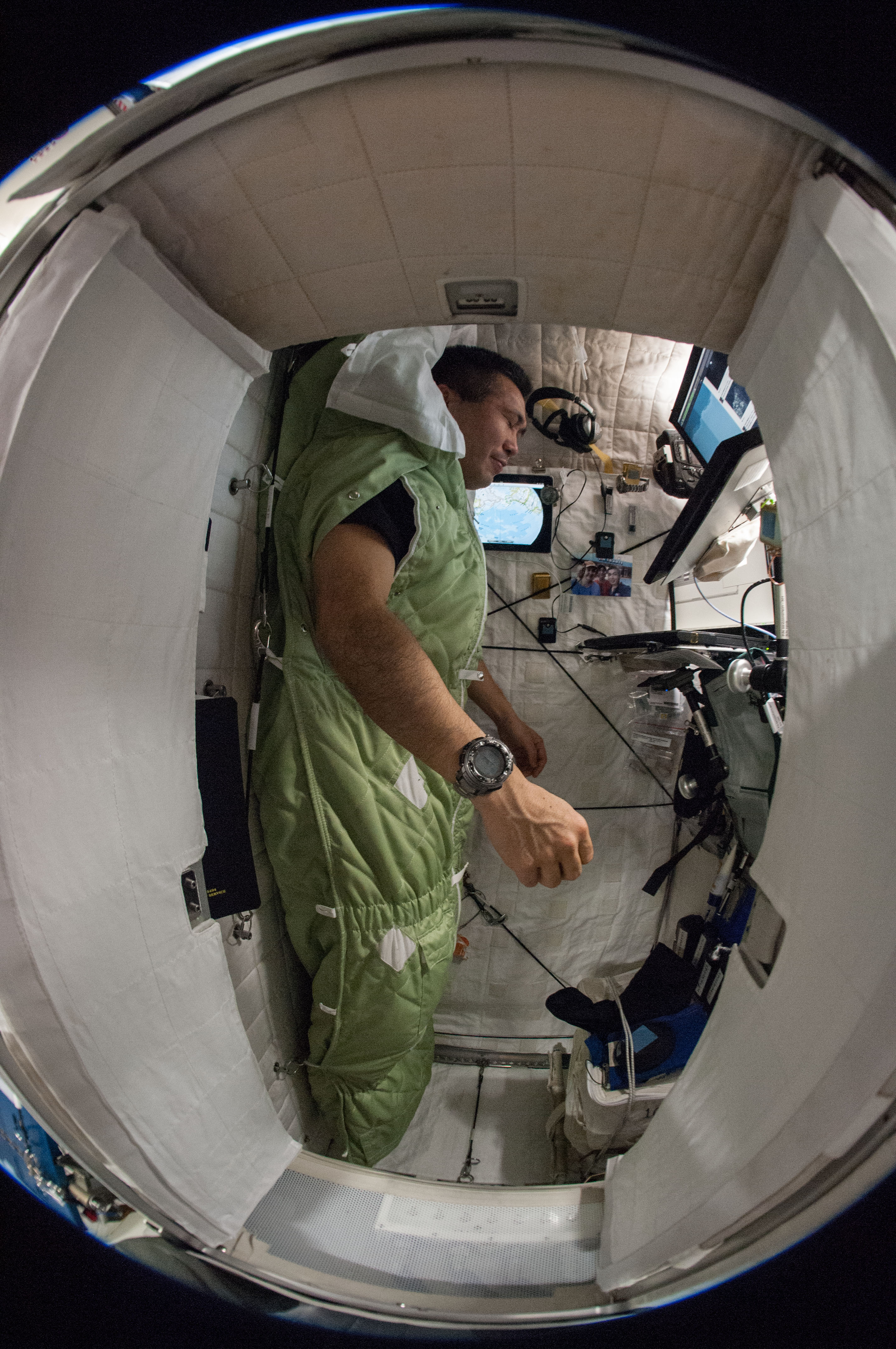

If an astronaut reports trouble sleeping during flight, NASA flight surgeons and psychiatrists can help diagnose the problem via video conferences, Moomaw said, even if there's no time to begin sleep-therapy sessions. "Sometimes, something very simple like CO2 [carbon dioxide] can be an issue. If the person is sleeping with their sleeping bag in such a manner that they develop a CO2 bubble in front of them, that will disturb their sleep."

High temperatures inside the sleeping bags can also keep astronauts awake, Moomaw said. Vents at the bottom of the bag allow heat to escape, but not if they're blocked. Both in space and on Earth, it's best to sleep in a cool environment.

"Everyone develops their own style of sleeping in space," Moomaw said. "Some people literally float pretty free — they may tether their bag at the shoulders, and that's it. There are other people who like to be simulating gravity by having some constraints on the bags so they feel more held in place."

Another environmental factor that can both help and hurt a person's sleep is lighting. Fluorescent lights and light-emitting diodes (LEDs) are popular for their bright light and efficient energy use. However, exposure to these types of lights close to the end of the day will have a negative effect on a person's ability to sleep at night, research has shown. That's because the spectrum of light emitted by these lights contains short-wavelength, or blue light, which, by producing hormones like cortisol, signals to the body that it's time to wake up. During the day, blue light helps to promote alertness. In the evening, blue light can suppress the body's natural production of the sleep hormone melatonin.

At the ISS, astronauts are currently working to install a new system of color-changing lights that create a lighting environment appropriate for the time of day. During the day, blue light keeps astronauts awake and alert. At the end of the day, the lights become less intense and stop emitting shorter wavelengths. Here on Earth, even if you don't have a fancy color-changing light, recognizing and avoiding sources of blue light (like smartphones, TVs and computer screens) before bed can help you fall and stay asleep at night, according to the National Sleep Foundation.

Medication

While sleep aids are available for astronauts who need them, medication is not a first line of treatment for astronauts on the ISS, Moomaw said. Instead, CBT is their first line of defense against insomnia and other sleep-related disorders.

"Most of the time, astronauts do not like taking meds, and we do everything that we can do to [make sure they do] not need medication," Moomaw said. However, sometimes astronauts choose to take a sleep aid the night before a big event such as a spacewalk just to be sure that they get the sleep they need, he said. "The only problem with the medication is that sometimes a person will do that pre-emptively and not wait until they have a problem sleeping," even though they might not have needed it, Moomaw said.

Before astronauts go to space, they test out all the available kinds of sleeping aids available on the ISS to determine "how they respond to particular medications and which ones actually work, and to make sure that there are no particular side effects so that when they get into space there are no surprises," Moomaw said.

Sleeping mindfully

Learning to recognize and control environmental factors, like lighting and temperature, that affect sleep is a big part of sleep CBT. But it's equally if not more important to learn the mental techniques that can help your mind and body drift off into sleep. This part of CBT, practicing mindfulness and relaxation, works the same for people on Earth and in space, Moomaw explained.

Just about everyone knows the struggle of being kept awake at night by an overactive mind. Racing thoughts brought on by worry, excitement or certain psychological disorders can make bedtime extremely frustrating. Sleep CBT aims to tame those monkeys of the mind using "progressive muscle relaxation, visualization, mindfulness and even wakeful relaxation as means of providing a psychological tool to get a person focused and be able to fall asleep and stay that way," Moomaw said.

While there are some major environmental differences between a bedroom on Earth and a sleeping pod at the ISS, "the basic components [of CBT] are the same," Moomaw said. "You want everyone to understand the mitigating factors, like writing down and journaling when you go to sleep, keeping animals out of the bedroom, keeping it dark and cool [and] very quiet … those are all just general, standard things that have to be done, and it's considered sleep hygiene that you do in your life, in your room and in your environment to promote sleep."

Email Hanneke Weitering at hweitering@space.com or follow her @hannekescience. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Hanneke Weitering is a multimedia journalist in the Pacific Northwest reporting on the future of aviation at FutureFlight.aero and Aviation International News and was previously the Editor for Spaceflight and Astronomy news here at Space.com. As an editor with over 10 years of experience in science journalism she has previously written for Scholastic Classroom Magazines, MedPage Today and The Joint Institute for Computational Sciences at Oak Ridge National Laboratory. After studying physics at the University of Tennessee in her hometown of Knoxville, she earned her graduate degree in Science, Health and Environmental Reporting (SHERP) from New York University. Hanneke joined the Space.com team in 2016 as a staff writer and producer, covering topics including spaceflight and astronomy. She currently lives in Seattle, home of the Space Needle, with her cat and two snakes. In her spare time, Hanneke enjoys exploring the Rocky Mountains, basking in nature and looking for dark skies to gaze at the cosmos.