Riding Along with Comets Using Mobile Astronomy Apps

Comets are some of the most captivating sights for skywatchers. These objects sweep across the sky with glowing green heads and glorious tails, powered by the sun's warmth and buffeted by its solar wind. The brightest comets, easily visible with naked eye, are legendary — but they're also extremely rare, often visible only from limited regions of the globe, and for only a brief time.

The arrival of new, bright comets is completely unpredictable, adding to their mystique. But one or two dimmer comets are usually observable in binoculars or small telescopes every month, if you know where to find these sights.

Some comets are one-time visitors that are flung out of the solar system by the sun or destroyed by its heat. Others traverse the solar system like interplanetary shuttle craft. In this edition of Mobile Astronomy, we'll show you how to use your astronomy app to replay comets' trips around the sun, either viewed from afar or riding along! And you'll learn how to track comets' motions across the night sky, so you can see these "hairy stars" for yourself. [Living on a Comet: 'Dirty Snowball' Facts Explained (Infographic)]

Comet basics

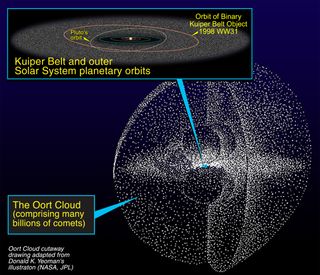

Comets, named using the Greek phrase for "having long hair," come from the Kuiper Belt and Oort Cloud, cold regions far beyond Neptune's orbit. There, primordial ice and other volatile elements survived, even after the newly formed sun cleared that material from between the planets. You can think of comets as "dusty icebergs" that are so low in density that you could crush a piece in your hand.

Astronomers believe that the gravitational tug of a passing star or an outer planet perturbs the equilibrium in those areas, triggering some of the icy bodies to fall toward the sun. The heat and radiation from the sun releases gas and dust from an icy body, producing the characteristic haze of material around the comet's nucleus, called the coma, as well as the comet's tail.

The sun's radiation ionizes some of the coma, causing it to glow with blue-green light. The ions align with the solar magnetic and electric fields around the comet, forming a straight ion tail pointed directly away from the sun. Meanwhile, the disintegration of the ice releases trapped dust and larger particles that are dropped in the comet's wake, like soil falling from a dirt-filled truck on a bumpy road. When the comet gets close enough to Earth, observers can see the ions glow, and observe the dusty tail lit by reflected sunlight.

Solar wind pressure pushes some of the lighter dust particles away. If the comet is traveling laterally as it approaches the sun rather than heading straight in, an interesting effect results: The difference between the travel directions of the comet and the solar wind causes the dust tail to curve in a spectacular arc. In fact, many comets sport a curved, yellowish dust tail in one direction and a straight, bluish ion tail in another direction.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As a comet drops toward the sun, it brightens and accelerates as it reaches perihelion, or its closest approach to the sun. Many comets plunge too close to the sun and are destroyed during perihelion. This was the case for Comet ISON in late November 2013. Scientists predicted that after perihelion, this comet would re-enter Earth's skies in spectacular fashion, but it instead disintegrated during its passage.

Some comets that survive perihelion are flung out of the solar system forever, making them one-time visitors only. The rest enter stable orbits that return them to the sun on periods of years to millennia.

In ancient times, no one knew that some comets returned periodically. In 1705, while researching historical records from previous comet appearances, English astronomer Edmund Halley noted that three comets shared the same orbit, and therefore were likely a single periodic comet. He calculated a return date, but died before the comet reappeared as predicted in 1759. It was named Halley's Comet (although it had been observed by many individuals since 240 BCE). [Photos of Halley's Comet Through History]

For the next 200 years or so, periodic comets were named for the discoverers who calculated the objects' orbits (although sometimes prior observers were added to the name). This became confusing, however, when the same people discovered several comets. The confusion was alleviated by numbering all periodic comets in order of discovery, starting with "1P/Halley." The list has reached "347P/PANSTARRS," discovered in 2016 using the Pan-STARRS digital sky survey.

Since 1995, new comets have been given designations that indicate their type, the date of discovery, and the discoverer. The prefixes designate the type of comet: "P/" for periodic, "C/" for nonperiodic, "X/" for uncertain, and "D/" for destroyed or lost. Appended to this are the year of discovery and a letter code indicating in which of the 24 half-months the comet was discovered, where "A" represents Jan. 1-15 and "Y" is Dec. 16-31 (with B-K covering the dates in between).

Next, a number indicates whether the object was the first, second, etc. comet discovered in that half-month. Finally, the names of any discovers or the name of the robotic camera system used in the discovery are appended. This system has been applied retroactively to all periodic comets, even ones that were already named, so many individual comets have multiple designations.

Seeing comets for yourself

Unlike planets and asteroids, comets can appear throughout the sky, because they whip around the sun with a wide range of orbital inclinations and eccentricities. They are brightest during the perihelion period, but at that time, they also change position rapidly. From one evening to the next, they can cross several moon diameters' worth of sky. In fact, when viewing a comet through a telescope, it takes only a few minutes to notice that the object is moving against the fixed stars!

Violent outbursts from the comet's nucleus can alter the object's orbit, too. All that movement makes mobile astronomy apps a far better option than magazine finder charts for locating comets.

Popular astronomy apps like SkySafari, Star Walk 2 and Stellarium Mobile include the prominent comets in their databases, and they regularly update the orbital data and add newly discovered comets.

Some of the apps track only comets that are currently available to observe. SkySafari 5 maintains a lengthy list that lets you view comets in the past, present or future. Navigate to the Search menu and scroll down to the Comets category. To find the comets that are brightest and easiest to hunt down, tap the Sorted By option and choose Visual Magnitude. The current brightest comets will be listed first, and the ones that are above your horizon will be highlighted.

Star Walk 2 doesn't offer sorting, but it does highlight the comets currently in your sky. SkySafari and Stellarium also allow you to search by typing in the comet's proper name or designation, such as "Encke" or "2P/Encke" or even just "2P."

The free Comet Book app for Android and iOS, from the makers of Vixen telescopes, does a good job of locating and showing the motions of current comets across the sky. On startup, the app downloads information for a half dozen comets currently available for observing. Stepping through the days clearly shows how quickly comets traverse the sky. The app includes a red night mode, so you can view the screen without disrupting your night vision, and it will activate your device's compass and gyroscope so you can hold the app against the sky to locate the comets.

The best times to hunt comets are during dark, moonless nights. Expect the comet to appear as a faint, greenish blob that appears quite different from a star, but resembles a galaxy. The object's tail, if it has one, will appear much fainter and will point away from the sun. If you use a telescope, be sure to search at low power (50x) initially, and then magnify to 150X or more once you have the comet in view. Don't be afraid to try taking long-exposure photographs, either through the eyepiece or via a tripod-mounted camera.

For celestial objects, the visual magnitude number increases as the brightness decreases. Under dark skies, a small pair of binoculars should show comets with visual magnitudes as faint as 9.5. Large binoculars and small telescopes will work to about magnitude 11, and an 8-inch (203 millimeters) reflector or SCT telescope can reach magnitude 14.

Here are four comets you can see now, or later this year. Prepare by reviewing a comet's information in your astronomy app to determine whether that object is available in your sky, the best time for viewing and the constellation in which to look. You can take your device with you, but be sure to enable red-light mode to preserve your eyes' dark adaptation.

41P/Tuttle-Giacobini-Kresak has a nucleus 0.9 miles (1.4 km) across, and a period of 5.42 years as it shuttles between Earth and Jupiter. This is an evening comet that moves across the northern sky, and it will be visible in binoculars and telescopes until at least the end of May. It's expected to reach peak brightness (visual magnitude 5.8) around the beginning of April. During March 23-25, it will traverse the Big Dipper's bowl. This comet is famous for suddenly brightening.

C/2015 V2 Johnson has an unknown nucleus size, and is a one-time comet passing 1.6 AU from the sun on June 12. This is a late evening and predawn comet located in the eastern sky near Hercules. It's visible in binoculars and telescopes until late 2017 and is expected to reach a peak brightness of visual magnitude 6 around perihelion.

C/2015 ER61 (PANSTARRS) has an uncertain nucleus size of between 2.5 and 12.5 miles (4 and 20 km). It's a long-period comet passing 1 AU from the sun on May 9. Look for it during the predawn period, crossing the low southern sky near Sagittarius. It's visible in large binoculars and telescopes until summer, and is expected to reach a peak brightness (visual magnitude 7) around May 9.

21P/Giacobini-Zinner has a nucleus 1.25 miles (2 kilometers) across and a period of 6.57 years, traveling in an orbit that ranges from Earth to Jupiter. Starting in midsummer, the comet will be visible in the southern evening sky near the constellation Virgo, and will be visible in binoculars and telescopes until it passes too near the sun after August. This comet is expected to reach peak brightness (visual magnitude 6) in September.

Watching a comet fly

With the SkySafari 5 app, you can choose any comet in the database and replay its trip through the solar system in two interesting ways: viewed from above the solar system or riding along with the comet. Here's how:

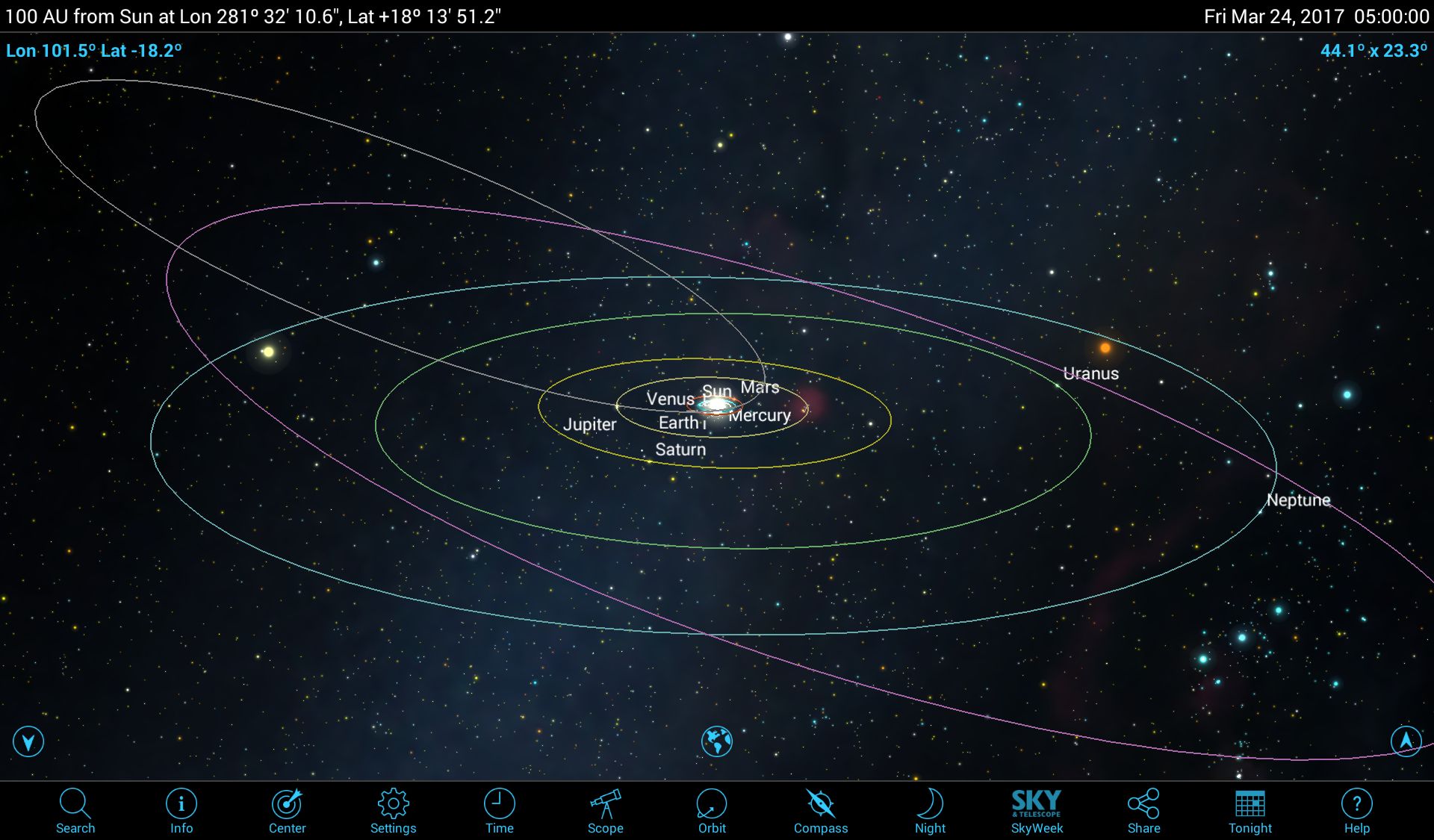

In the app settings, under Solar System, switch on the option for Selected Object Orbit. Next, search for the sun, then tap the Orbit icon. You will see the 3D model of the solar system showing colored orbits of the planets. Next, search for a comet by typing its name or scrolling through the provided list to find it. Select the comet and exit the search menu. The comet's elliptical orbit will now appear among the planets in a model of the solar system. While in this mode, you can rotate, pan and zoom to see the size and shape of the orbit.

Notice the extreme orbital inclination of most comets' orbits. Comet Halley's 75.5-year orbit extends out to Neptune, while little Comet 2P/Encke, which returns to Earth's vicinity every 3.3 years, ranges only between Mercury and the asteroid belt. The orbit of the now-disintegrated Comet ISON — and the current orbit of that comet's debris heading outward from the sun, which the app still tracks — is highly elongated and open. [Green Comet Lovejoy Photobombs Night Sky Photos by Stargazers]

It's a lot of fun to explore comets this way. To see a comet traveling, open the time controls and adjust the date forward and backward. When the comet is far from the sun, increments of months are better. But near perihelion, try stepping by day or hour. Tapping Now will always return you to the present.

The other way to see the comet in action is to ride along with it. The setup is the same as above, except that you'll tap the Orbit button when in the comet's information window. You may need to pinch the display to zoom out enough to see the rest of the solar system. As the comet reaches the perihelion date, the sun will loom larger, and then the star will retreat afterward. To exit both app configurations, tap the Earth icon, then switch off the Selected Object Orbit feature. Enjoy!

Going beyond

Periodic comets are the primary source for meteor showers. After many orbits, the dropped material accumulates into an elongated zone of fine-grained debris, which Earth's orbit can intersect. As the planet passes through them every year on the same dates, the particles burn up as meteors in the atmosphere; the duration of the shower depends on the width of the zone. Halley's Comet is responsible for the Eta Aquarid and Orionid meteor showers. Your astronomy app will have a meteor shower index.

There are good websites to tell you what comets are observable. Cometchasing.skyhound.com lists current and upcoming comets, ranked in order of visibility, with notes about when and where to look and what instrument is required (naked eyes, binoculars, small telescope, etc.). Links provide a printable finder chart showing each comet's path over the month.

Seiichi Yoshida's Weekly Information About Bright Comets provides observing notes, finder charts, recent photographs and a light curve showing a comet's predicted brightness profile over time as well as brightness estimates contributed by observers. His Visual Comets in the Future page lists the comets observable during the evening, midnight and predawn times, month by month into the future.

The last truly magnificent naked-eye comet was 1996-97's Hale-Bopp, which shone almost as bright as Venus for many months and sported a tail stretching over many degrees of sky. Until the next great comet appears, skywatchers can enjoy the many smaller ones that are available from time to time, and travel the solar system with astronomy apps.

In the next edition of Mobile Astronomy, we'll show you how to use your mobile astronomy app to plan for the Great American Total Solar Eclipse of Aug. 21, 2017. Until then, keep looking up!

Editor's note: Chris Vaughan is an astronomy public outreach and education specialist, and operator of the historic 1.88-meter David Dunlap Observatory telescope. You can reach him via email, and follow him on Twitter as @astrogeoguy, as well as on Facebook and Tumblr.

This article was provided by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of the SkySafari app for Android and iOS. Follow SkySafari on Twitter @SkySafariAstro. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chris Vaughan, aka @astrogeoguy, is an award-winning astronomer and Earth scientist with Astrogeo.ca, based near Toronto, Canada. He is a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and hosts their Insider's Guide to the Galaxy webcasts on YouTube. An avid visual astronomer, Chris operates the historic 74˝ telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory. He frequently organizes local star parties and solar astronomy sessions, and regularly delivers presentations about astronomy and Earth and planetary science, to students and the public in his Digital Starlab portable planetarium. His weekly Astronomy Skylights blog at www.AstroGeo.ca is enjoyed by readers worldwide. He is a regular contributor to SkyNews magazine, writes the monthly Night Sky Calendar for Space.com in cooperation with Simulation Curriculum, the creators of Starry Night and SkySafari, and content for several popular astronomy apps. His book "110 Things to See with a Telescope", was released in 2021.