Old Weather Satellite Headed to 'Graveyard Orbit'

A satellite that's watched Earth for 20 years is retiring to a so-called graveyard orbit high above the Earth that puts out-of-commission satellites out of harm's way. Although the satellite, Meteosat-7, was only designed for about five years of use, it's sent meteorological data back to Earth for nearly two decades.

Satellites in low-Earth orbit save enough fuel to redirect downward and eventually burn up in the atmosphere, to reduce crowding in active orbits. But some satellites like this retiring one, called Meteosat-7, are too high to make it to that final burn-up stage without carrying way too much extra fuel. Instead, Meteosat-7 will begin a complicated series of maneuvers to come to rest in a region at least 125 miles (200 km) above the highest active satellites, according to a statement from the European satellite-monitoring agency EUMETSAT.

Meteosat-7 orbits high in geostationary orbit, 22,000 miles (36,000 km) above Earth's surface, always staying above the Indian Ocean. Geostationary orbits are the highest Earth orbits satellites use — more than 21,000 miles (35,000 km) higher than the International Space Station, which is in low Earth orbit — and they stay put over one particular part of the surface as Earth rotates. [How to Spot the International Space Station & Satellites]

From its current perch, Meteosat-7 monitors Africa, Europe and part of South America, and when it departs in the spring, a recently-relocated satellite, Meteosat-8, will take over.

Under requirements set by the International Organization for Standardization, satellites that can't reach Earth's atmosphere for burn-up must be equipped to reach a geostationary orbit of a certain altitude, EUMETSAT officials said in the statement. So it's really more of a graveyard region than graveyard orbit.

"You must target, with 90 percent probability, that you will clear this 200 km-plus region," Milan Klinc, a flight dynamics engineer at EUMETSAT, said in the statement. "We will most probably reach 500 km to 600 km [310 to 370 miles] above the geostationary protected region with Meteosat-7."

Then, the satellite will get rid of as much leftover propellant as possible; discharge and disconnect its batteries; fire any remaining explosives (used on one-time tasks such as releasing payloads); and switch off its equipment, officials said in the statement.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

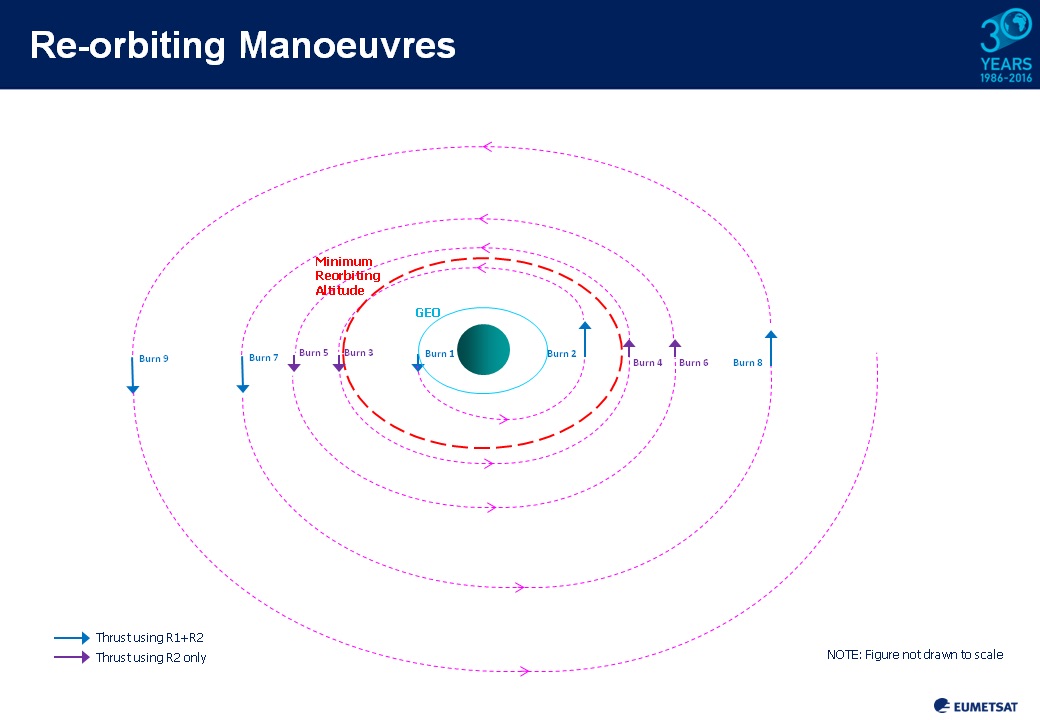

Meteosat-7's path to the graveyard is a long one: It will increase its altitude every half orbit over a series of several burn maneuvers.

"We have designed it so that after burn number three, we will have cleared the protected region," Klinc said in the statement. "We have allowed a margin for uncertainties and will keep maneuvering higher up, with up to nine burn maneuvers."

At the same time, the satellite will use specific thrusters during its maneuvers that will slow down its rapid spin over time, so any equipment that eventually broke away over time will not be flung out of its new resting orbit — during its time in action, the satellite rotated about 100 times per minute. Klinc pioneered this technique on Meteosat-5 and Meteosat-6, both of which slowed their spins significantly without using extra fuel, according to the statement, and both of which now reside high above the active orbits around Earth.

As Klinc said, the graveyard orbit isn't a single orbit, but rather a region. And the term is possibly inaccurate in another way, too, Klinc added: it might not be the satellites' ultimate resting place. Someday, the region may need to be cleared out as space fills with debris, spacecraft and satellites.

"Space debris is a major problem," Klinc said. "We recognize that the graveyard orbit can only be a temporary solution. We are only in the early, theoretical stages at the moment, but we need to look at a permanent solution involving removing or collecting the old satellites."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.