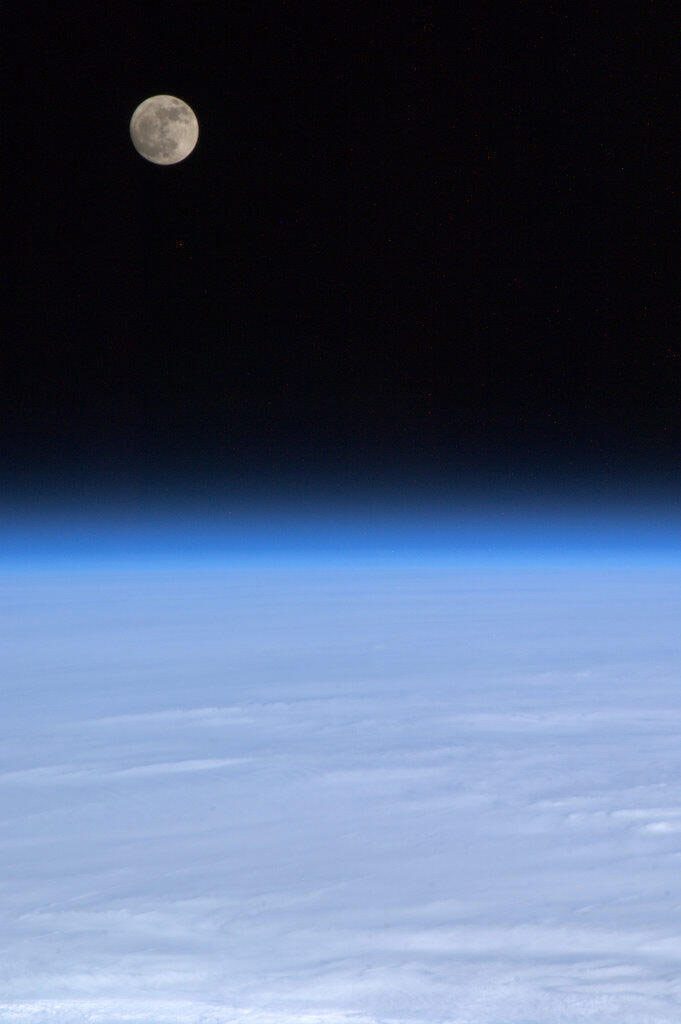

The Full Moon that Determines Easter

Have you ever wondered how the date of Easter is actually set? It is all based on the moon.

The day to be observed as Easter was fixed by a great council of Christian churches, called the First Council of Nicaea, which met at Nicaea (now İznik, in the province of Bursa, Turkey) in A.D. 325. Under the Nicaean rule, Easter is celebrated on the first Sunday following the fourteenth day of a particular new moon — the one that begins on or after the vernal equinox. [2017 Full Moon Calendar]

Put another way, Easter falls on the Sunday that follows the first full moon occurring on or the day after the March equinox. If the full moon occurs on a Sunday, however, then Easter is observed the following Sunday.

This year, the fourteenth day of this particular new moon was on April 11 (Eastern Daylight Time), which was a Tuesday. So the following Sunday, April 16, is designated as Easter.

When the Council of Nicaea met, Easter was already the most important festival of the church calendar, and it was the custom of thousands of Christians to make long pilgrimages to Jerusalem and other shrines to celebrate the Resurrection. The rule of the Council of Nicaea was established to make it certain that the pilgrims would always have the light of a full moon to guide them on their way at night.

Unfortunately, sometimes there is confusion about how to properly set the date for when Easter should fall in our current Gregorian calendar.

Calendar discontinuities

For astronomers, the moment of a "full" moon comes when our natural satellite is directly opposite from the sun in our sky. But there is also an "ecclesiastical" full moon. The latter, which originated with the Christian Church, was determined from ecclesiastical tables (epacts and "Golden Numbers"). And the church's date does not necessarily coincide with the date of the "astronomical" full moon, which is solely based on astronomical calculations.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

And then there is the problem involving the vernal equinox. Ecclesiastical rules also state that the vernal equinox always occurs March 21, even though from the years 2008 through 2101 it will actually occur no later than March 20 at European longitudes.

As a result, we occasionally end up with discrepancies. From the years 1583 to 2582, for example, there are 78 years in which the date of "astronomical Easter" differs from that of the traditional, "ecclesiastical Easter."

Perhaps the most noteworthy is the dating for Easter in 2038. In that year, astronomically speaking, Easter should fall on March 28: The equinox falls on March 20, with a full moon the next day. However, according to the church's rules, Easter will occur on its latest possible date — April 25.

Conversely, Easter can come as early as March 22. That last happened in 1818, but it will not happen again until the year 2285, although as recently as 2008, we came within a day of that extreme: Easter occurred in that year on March 23. So, there are 35 dates on which Easter can fall.

From the years 2000 to 2999, Easter falls on March 22 just five times. In the same 1,000-year time frame, the latest Easter date of April 25 comes up twice as many times: 10. During this same time period, the date that comes up the most (41 times) for celebrating Easter is April 16, which also just happens to be this year.

Since the beginning of the 20th century, people have been circulating a proposal to choose a fixed date for Easter, rather than having a movable one. In 1963, the Second Vatican Council said that it would agree if a consensus on that date were reached among Christian churches — and the second Sunday in April has been put forward as the most likely date. That happens to work out quite well this year. [Best Night Sky Events of April 2017 (Stargazing Maps)]

Wild swings of the weather pendulum

Because Easter is a movable feast, and its placement in the calendar occurs during a time when the weather in temperate latitudes is transitioning from winter to spring weather conditions, the actual weather that can occur on Easter can vary quite a bit. We are accustomed to associating cold and snow with Christmastime, and hot and sultry weather with Independence Day. And yet, Easter weather can reflect the very same characteristics of both extremes.

Take, for example, Easter 1970 in the Greater New York area. In that year, Easter Sunday fell on March 29, and that was the day that a late-season snowstorm blanketed New York City with 4 inches of snow, while to the north, Westchester and Putnam counties received as much as 9 to 12 inches. Six years later, in 1976, Easter Sunday occurred on April 18, right in the middle of a three-day stretch of what is now known in weather annals as New York's Great Easter Heat Wave. Temperatures each day reached to above 90 degrees, but Easter was the hottest day. Not only was it the hottest Easter on record in Gotham, but it was also the very first (and only) time that New York had the highest temperature in the nation: In Central Park the thermometer hit a blistering 96 degrees!

That was probably the first time you could have fried an Easter egg on a New York sidewalk.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for Verizon Fios1 News, based in Rye Brook, New York. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.