What appears to be a huge plume of water vapor has again been spotted emanating from Jupiter's icy moon Europa, boosting scientists' confidence that the phenomenon is real.

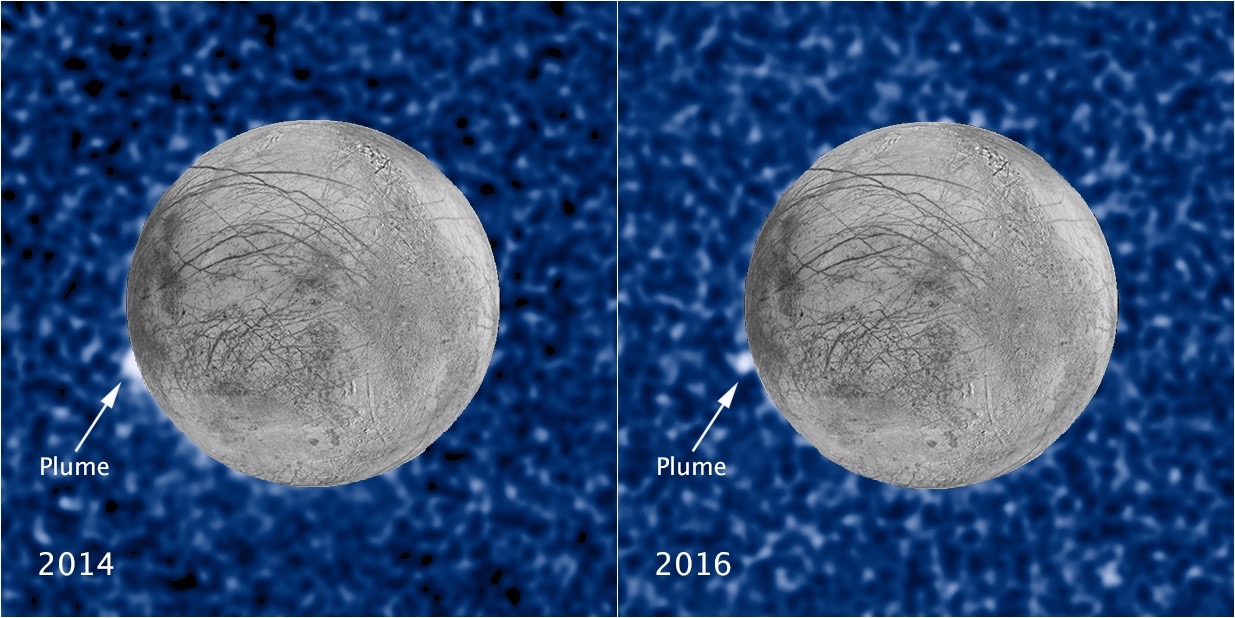

NASA's Hubble Space Telescope detected a 62-mile-high (100 kilometers) candidate plume near Europa's equator in February 2016, researchers and agency officials announced today (April 13).

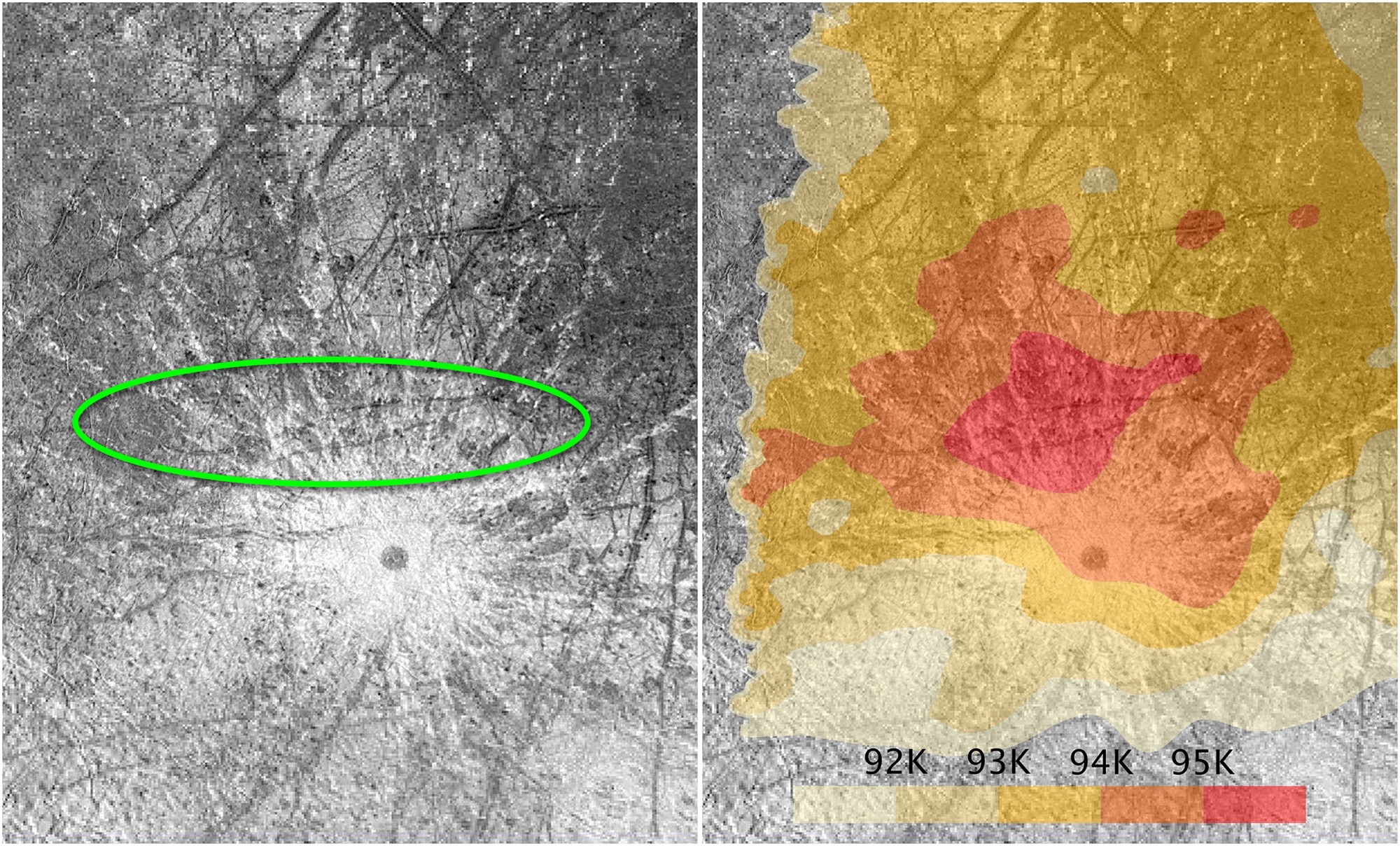

The newly reported candidate is in the same location as a smaller one that Hubble saw back in March 2014. And that location is right in the middle of an unusually warm part of Europa's surface identified by NASA's Galileo Jupiter probe in the late 1990s. [Photos: Europa, Mysterious Icy Moon of Jupiter]

These results are highly suggestive but don't quite rise to the level of a definitive plume confirmation, researchers said.

"It's not completely unequivocal, but in my mind, the pendulum has swung from caution to optimism," project team leader William Sparks, of the Space Telescope Science Institute in Baltimore, said during a press conference today.

Hunting for elusive plumes

A huge ocean of liquid water sloshes beneath Europa's icy shell, making the 1,900-mile-wide (3,100 km) moon one of the solar system's best bets to host alien life. (Many astrobiologists rank Europa and Saturn's geyser-blasting, ocean-harboring moon Enceladus as the top two such candidates.)

A different research group first spotted an apparent plume coming from Europa's south polar region in late 2012, also using Hubble. Astronomers tried repeatedly to confirm the phenomenon but kept coming up empty — until early 2014, when Sparks and his team detected one near the moon's equator.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The March 2014 detection (which the researchers announced in September 2016) and the newly announced one were both made using the "transit technique." As Europa passed in front of Jupiter from Hubble's perspective, the putative plumes blocked some of the ultraviolet light emitted by the giant planet.

"The fact that we've got a repeat tells you that, in a formal statistical sense, it can't happen by chance," Sparks said today.

"So we have to look for systematic effects that might cause it," he added, referring to issues such as instrument artifacts. "We don't know of any, which is why most of us, some of us, are leaning towards thinking that this means [the plumes are] real."

Bolstering that interpretation is the thermal imaging performed by Galileo two decades ago, which shows a "hotspot" at the location of the 2014 and 2016 plume candidates.

If the thermal anomaly and the plumes are indeed causally linked, there are two possible explanations, researchers said. Water venting through cracks in Europa's ice could be warming the surface, or water from the plume may be falling back down onto the hotspot, changing the fine structure of the surface and allowing it to hold onto heat longer, they said.

Flying through the plumes?

The detection of plume candidates is influencing the planning of NASA's $2 billion Europa Clipper mission, which the agency aims to launch in the early to mid-2020s.

The Europa Clipper will settle into orbit around Jupiter, then perform 40 to 45 flybys of Europa over the course of several years. The solar-powered probe will use a number of different instruments to study the moon's ice shell and underlying ocean, gathering data that should help scientists assess Europa's ability to support life as we know it.

Clipper will also hunt for Europa's plumes and, if possible, fly through them, as NASA's Cassini spacecraft has done with the powerful and ever-present plume of Enceladus, said Jim Green, director of NASA's Planetary Science Division.

Plume plunges would allow Clipper to snag samples of Europa's vast, buried ocean without even touching down, agency officials have said.

"If there are plumes on Europa, as we now strongly suspect, with the Europa Clipper, we will be ready for them," Green said in a statement.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.