Distant Dwarf Planet DeeDee Stirs Up the Pluto Planethood Debate

What's a planet? What's a dwarf planet? Should we make a distinction? Should we really care about these definitions in the first place?

As we learn more about the outer solar system, the boundaries begin to blur.

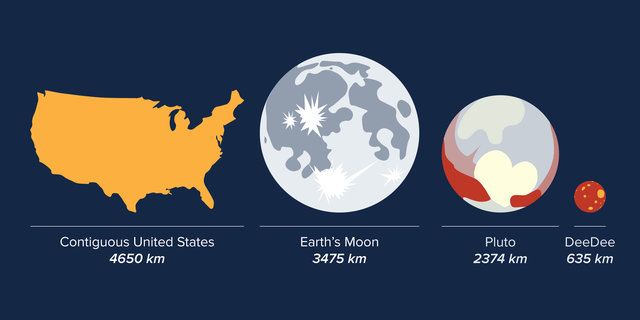

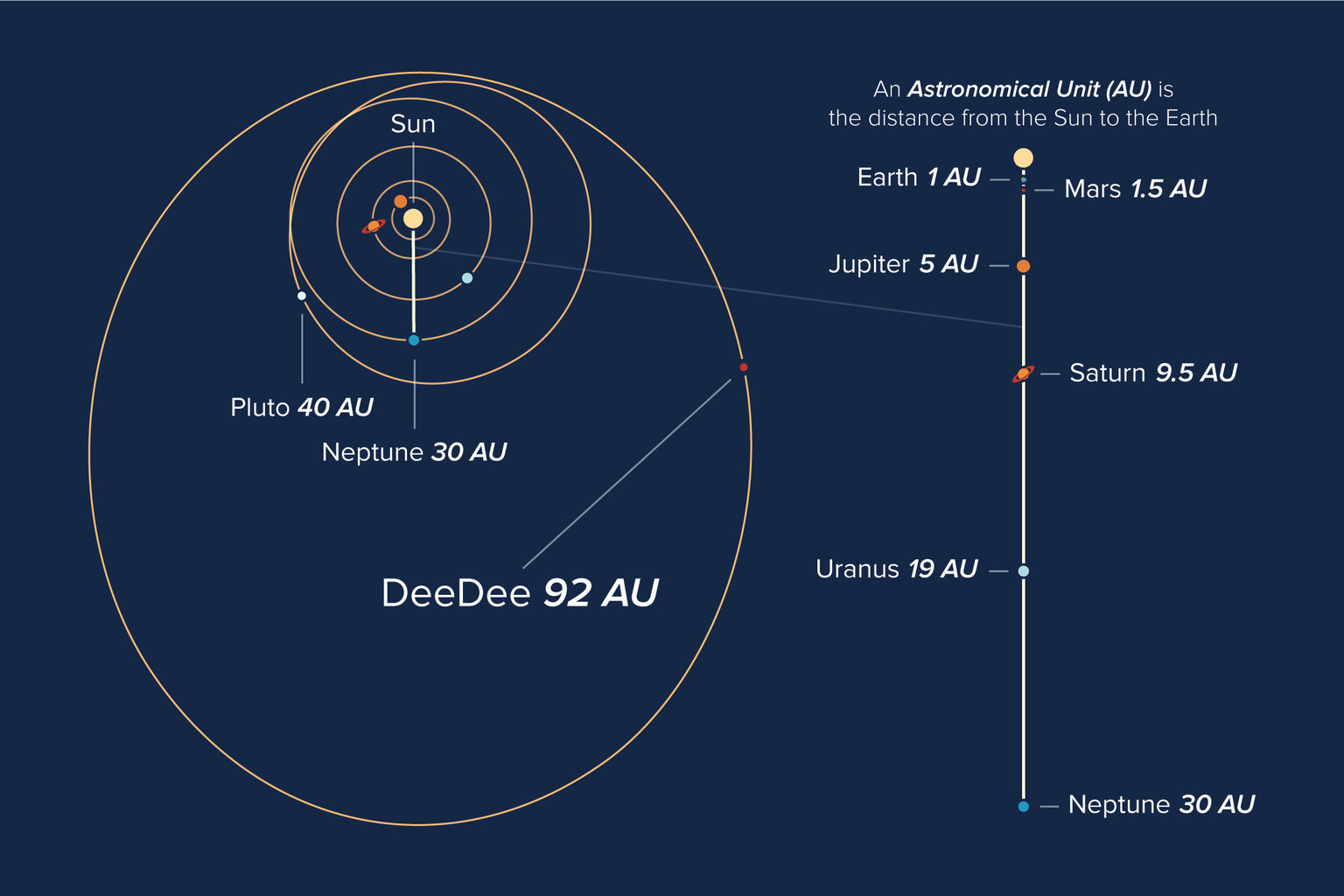

A tiny celestial body called 2014 UZ224 and informally known as DeeDee (for “distant dwarf”) is a distant world about 92 astronomical units, or Earth-sun distances, from our sun. Recent observations from the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) revealed that DeeDee is roughly 395 miles (635 kilometers) across, which would give it enough mass to be spherical.

Why does it matter if DeeDee is round? In 2006, a controversial vote by the International Astronomical Union defined three parameters for a planet. Simply speaking, the IAU says a planet must be in orbit around the sun, have enough mass to be round, and have cleared the neighborhood around its orbit — meaning it needs to be gravitationally dominant and hold any nearby bodies within its orbit.

It's the last part of the definition that most aggravates those who argue that Pluto – redefined as a "dwarf" planet under the IAU – is more planet than not. The argument is that the rocky planets of Earth, Mars, Venus, and Mercury have also not cleared their neighborhoods, as many asteroids co-orbit along with them.

The planetary geologist Kirby Runyon, a Ph.D. student at the Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, wrote a paper this year proposing a geophysical-based definition of a planet that would dispense with the orbital criterion and basically include any round celestial body that isn’t a star. The idea hatched by Runyon and his co-authors — which include Alan Stern, the principal investigator of the New Horizons mission to Pluto — would increase the number of purported planets in our solar system to over 110, including Earth’s moon and DeeDee.

RELATED: Behind the Push to Get Pluto Its Planetary Groove Back

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"What it's really showing is the diversity of planets in our solar system,” said Runyon of the DeeDee news, “and giving us a better understanding of planets in the rest of the galaxy.”

"DeeDee is almost certainly made out of ices — water ices, methane, and carbon dioxide — which is similar to what Pluto is made of," he added. "These are very soft materials, compared with rocky silicate. It's more easily pulled into a sphere than rock or metal."

Adding more fodder to the debate over the definition, when the New Horizons spacecraft flew by Pluto in 2015, it unveiled a world of surprising complexity, ranging from mountainous areas to vast nitrogen-ice lakes.

"We call Pluto a 'dwarf' planet, but it's just an adjective for 'planet,’” Runyon said. “It's still a planet, and that's where we take umbrage with the IAU.”

"Astronomers aren't experts in planetary science, and they basically passed a bunch of B.S. off on the public back in 2006 with a planet classification so flawed that it rules the Earth out as a planet, too," Stern remarked in 2016. "A week later, hundreds of planetary scientists, more people than at the IAU vote, signed a petition that rejects the new definition. If you go to planetary science meetings and hear technical talks on Pluto, you will hear experts calling it a planet every day."

RELATED: Remind Me Again, Why Isn't Pluto a Planet?

As a geomorphologist, Runyon is most particularly interested in the shape of landforms on worlds around the solar system. His dissertation deals with wind-blown sand geology on Mars, as mapped by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter's HiRISE (High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment) camera.

But he'll still keep his eye on the outer solar system. New Horizons is set to fly by a tiny world called 2014 MU69 on Jan. 1, 2019. While MU69 is too small to be even a dwarf planet, Runyon will be looking for features on MU69 such as ripples, which were also seen during the Rosetta mission during observations of Comet 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko. He'll also look at the shape of craters, among other things.

"MU69 has never warmed up since the formation of the solar system," he said. "It will be really interesting to see how different or complex it might be. There's a laundry list of things we'll be looking for, and hopefully we'll be surprised."

Originally published on Seeker.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.