Color-Changing U.S. Stamp Will Herald 2017 Total Solar Eclipse

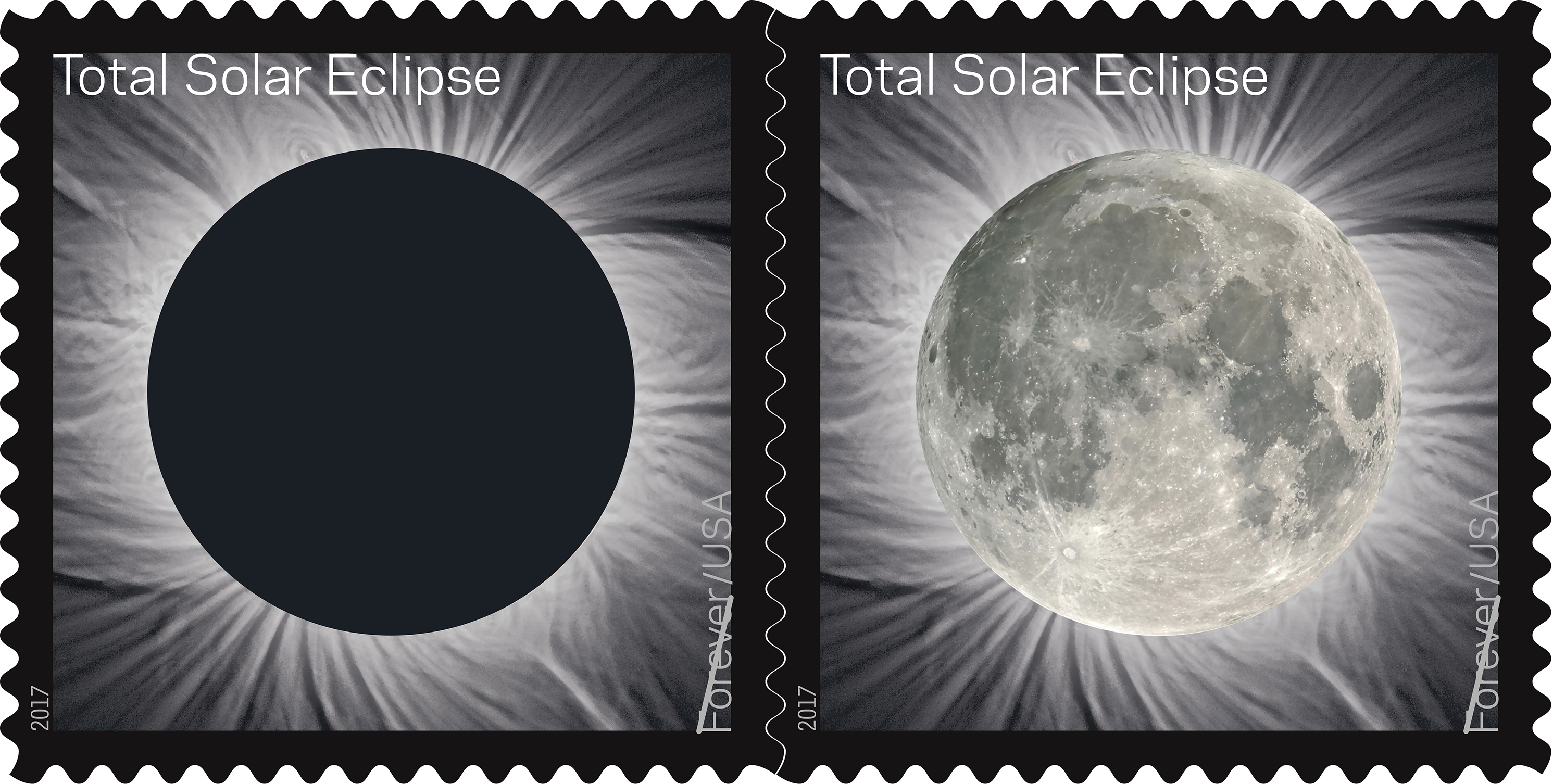

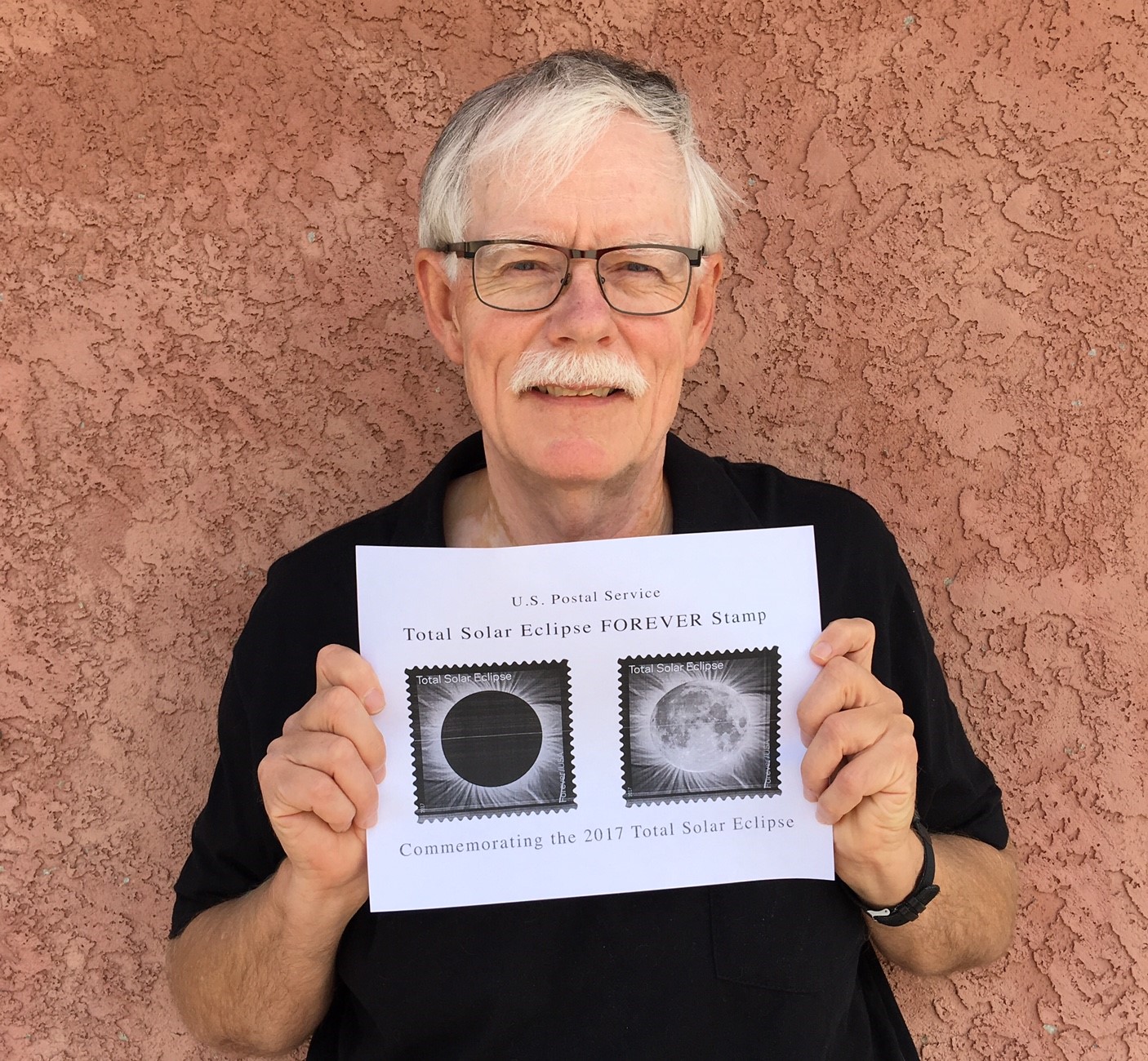

Just as a total solar eclipse will change the skies over the continental United States on Aug. 21, a newly released U.S. stamp will change when pressed with a finger — a photo of the moon materializing over the blotted-out sun. The photographs come courtesy of astrophysicist Fred Espenak, who has seen 20 solar eclipses, including one on every continent.

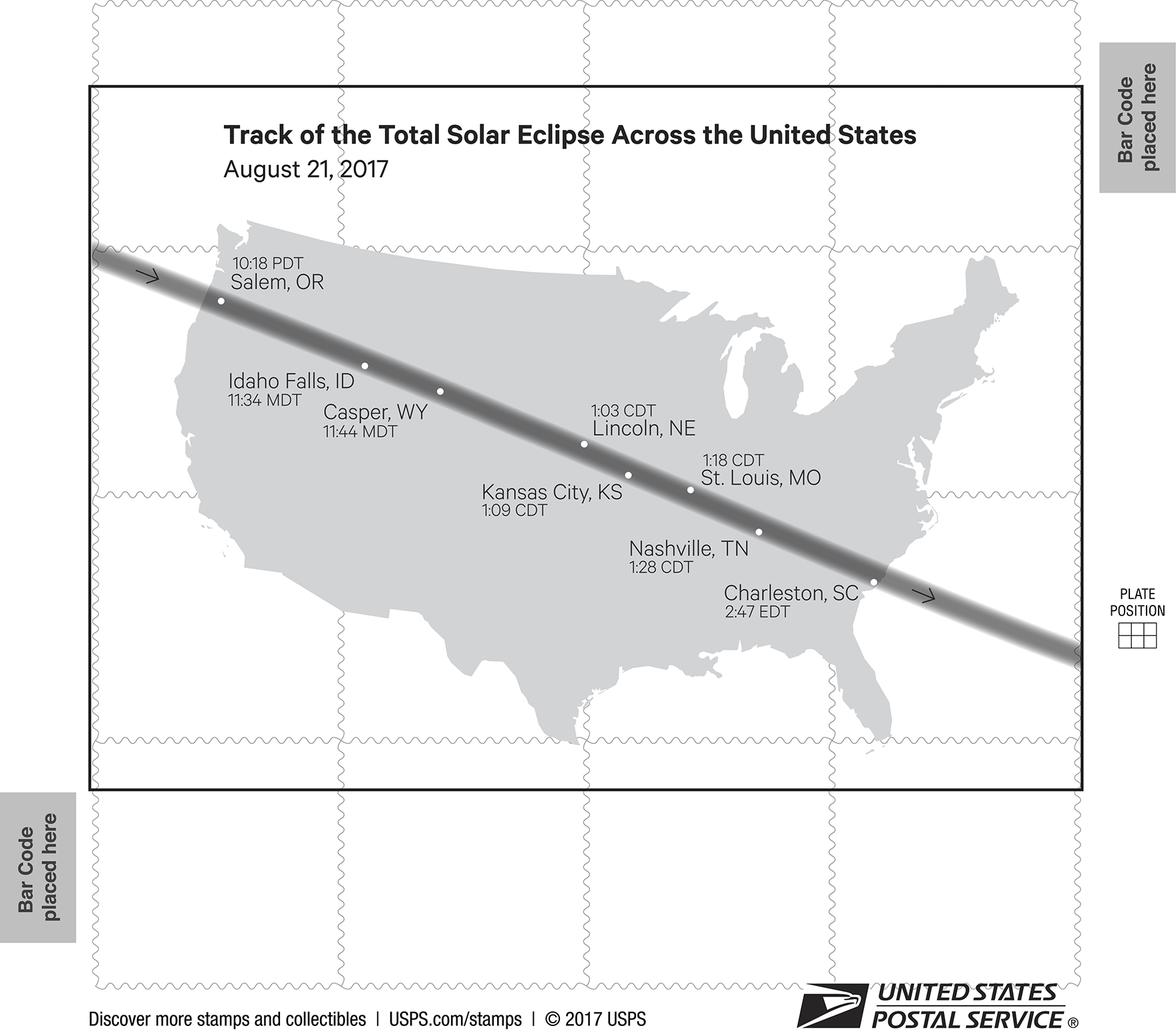

The 2017 total solar eclipse, which some are calling the Great American Eclipse, will be the first to cross coast-to-coast since 1918; parts of 14 states will enjoy views of the total eclipse, and many more will have partial views of the spectacle. The last time a total solar eclipse was visible anywhere over the continental U.S. was 1979.

To celebrate, the U.S. Postal Service is releasing a stamp June 20 that features a stunning view of the sun's outer atmosphere, called a corona, blotted out by the moon — as well as the moon itself, which appears when heated. Both images were taken by Espenak, who saw his first total solar eclipse in 1970 before he became "hooked on the shadow," as he said. [Total Solar Eclipse 2017: When, Where and How to See It (Safely)]

"I'm thrilled to death," Espenak told Space.com about the choice of his photographs. "This is a great honor, to have my photographs on the stamp to commemorate the 2017 eclipse. The eclipse is a phenomenal opportunity for millions of people to experience astronomy firsthand … with their own eyes, with nothing between them and the sky." [Awesome Space Stamps Through History (Gallery)]

Espenak shot the eclipse photo in Libya in 2006, and the moon photo comes from his home state of Arizona around six years ago, he said.

According to a Postal Service statement, the stamp is being released in conjunction with the summer solstice, and its First-Day-of-Issue ceremony will be held at the University of Wyoming.

The stamps are the first ever to feature thermochromatic ink, which will change to reveal the moon photo when rubbed. As it cools off, the moon will become obscured again. The stamps will be Forever stamps, which means they'll always be sufficient to carry a 1-ounce piece of first-class mail. The back of the stamp pad features a map of the eclipse path, detailing eight major cities that will be able to see the total solar eclipse and the times that totality will occur.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Espenak, whose website "Mr. Eclipse" provides a comprehensive resource for viewing and photographing eclipses, advises that people outside the path of totality should still try to make it to a city along that path on Aug. 21 — even if it means staying somewhere miles away and driving to the location in the early morning.

"There's no way to oversell how spectacular and incredible seeing a total solar eclipse is," Espenak said. "A lot of people think they've seen an eclipse, [but] even if they've seen a 99 percent partial [eclipse] it pales in comparison to seeing a complete, 100 percent total eclipse of the sun."

Viewers must wear eclipse glasses to view a partial solar eclipse safely, but once the sun is completely obscured it's safe to look with the naked eye.

And as for the stamps?

"I'll be ready to line up and buy hundreds of them," Espenak said. "I expect to buy a lifetime's supply of stamps when this comes out."

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.