NASA's Alien-Planet Hunter Spacecraft Gets a New Look at Neptune

The Kepler space telescope, NASA's dedicated exoplanet hunter, has provided a new look at the gas giant Neptune, and the observations could reveal more about much farther worlds that lie outside our solar system.

Neptune passed into Kepler's field of view between November 2014 and January 2015, when the spacecraft's orientation kept its instruments pointed along the plane of the solar system, according to a statement from the agency. When Neptune drifted into its line of sight, Kepler was able to collect the sunlight reflected off the planet and its two largest moons.

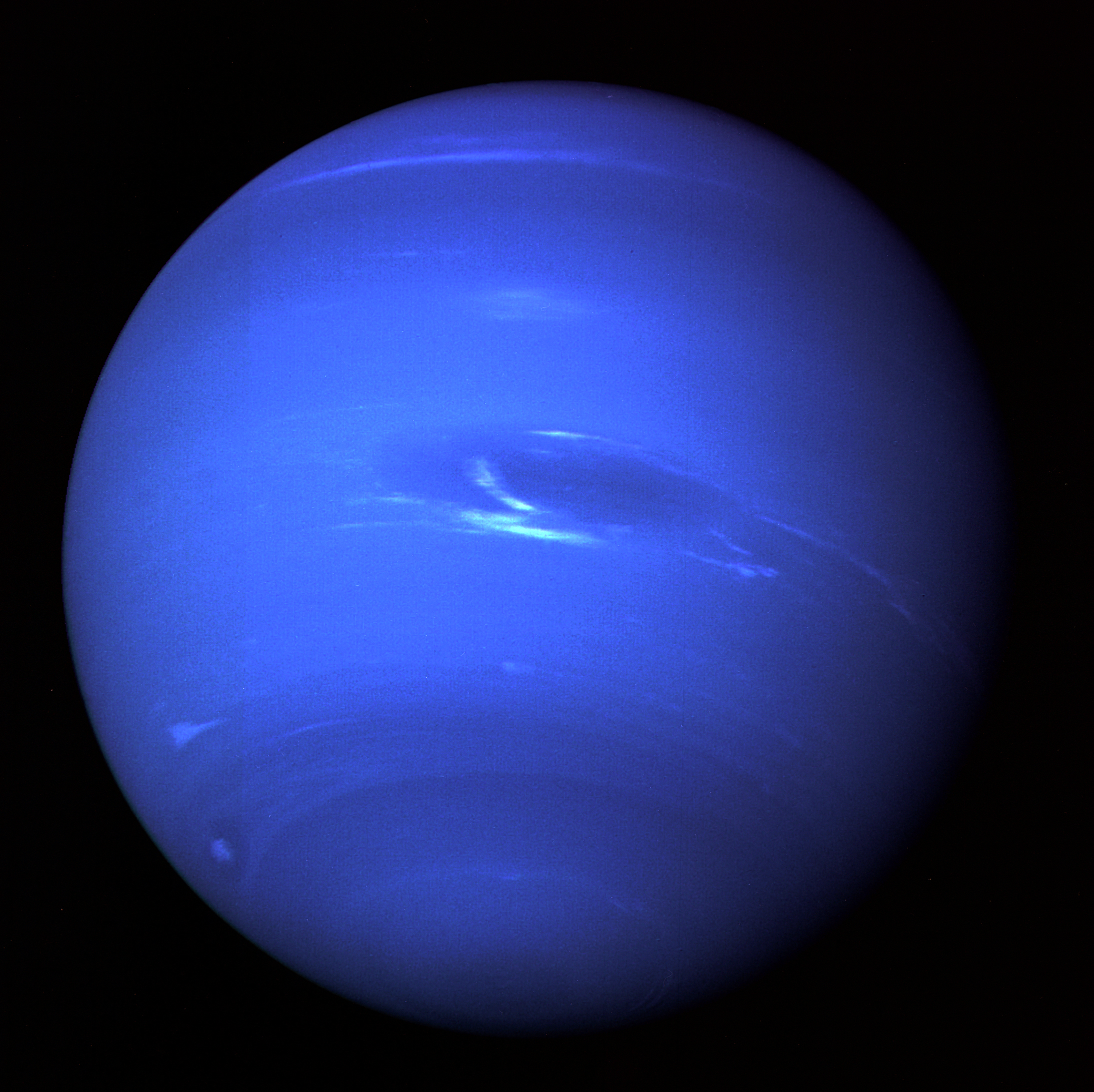

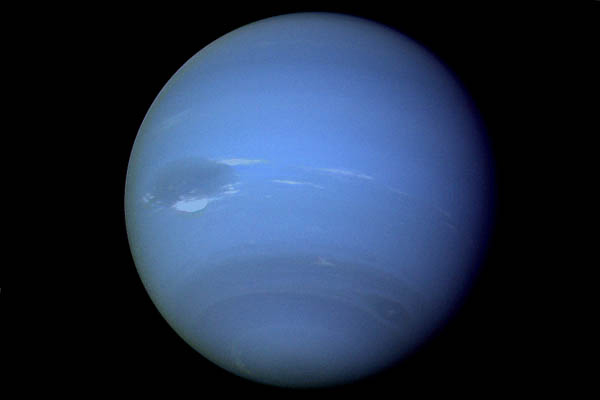

The spacecraft detected small changes in the planet's brightness, according to this new video from NASA. Scientists compared the Kepler data showing brightness fluctuations of less than 1 percent with direct observations of Neptune, and determined that the variations were caused, in part, by clouds on Neptune's surface, which reflect sunlight.

The Kepler telescope is designed to find planets using a technique known as the transit method. When a planet orbiting a distant star passes between that star and Earth — transiting across the bright face of the star — the planet blocks a small amount of light from the star, which Kepler can then detect. This method has helped scientists identify thousands of alien planets.

The Neptune study can help scientists interpret the data that Kepler collects on exoplanet systems, which are often too far away to observe directly. On the other hand, Neptune is close enough to Earth that its surface can be imaged by instruments such as the Hubble Space Telescope.

"The Kepler observations are unique, because they allow us to see the light curve of an object close enough to image and resolve cloud features," Amy Simon, a planetary scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, said in the statement. "These observations prove that rapid variations in light curves of brown dwarfs and exoplanets can be caused by changing clouds."

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter