Not So Fast: Magnetic Mystery of Sun's 'Stealth' Eruptions Uncovered

Solar astronomers have uncovered the magnetic secrets behind one of the sun's most mysterious eruptions: a coronal mass ejection that seems to come from nowhere.

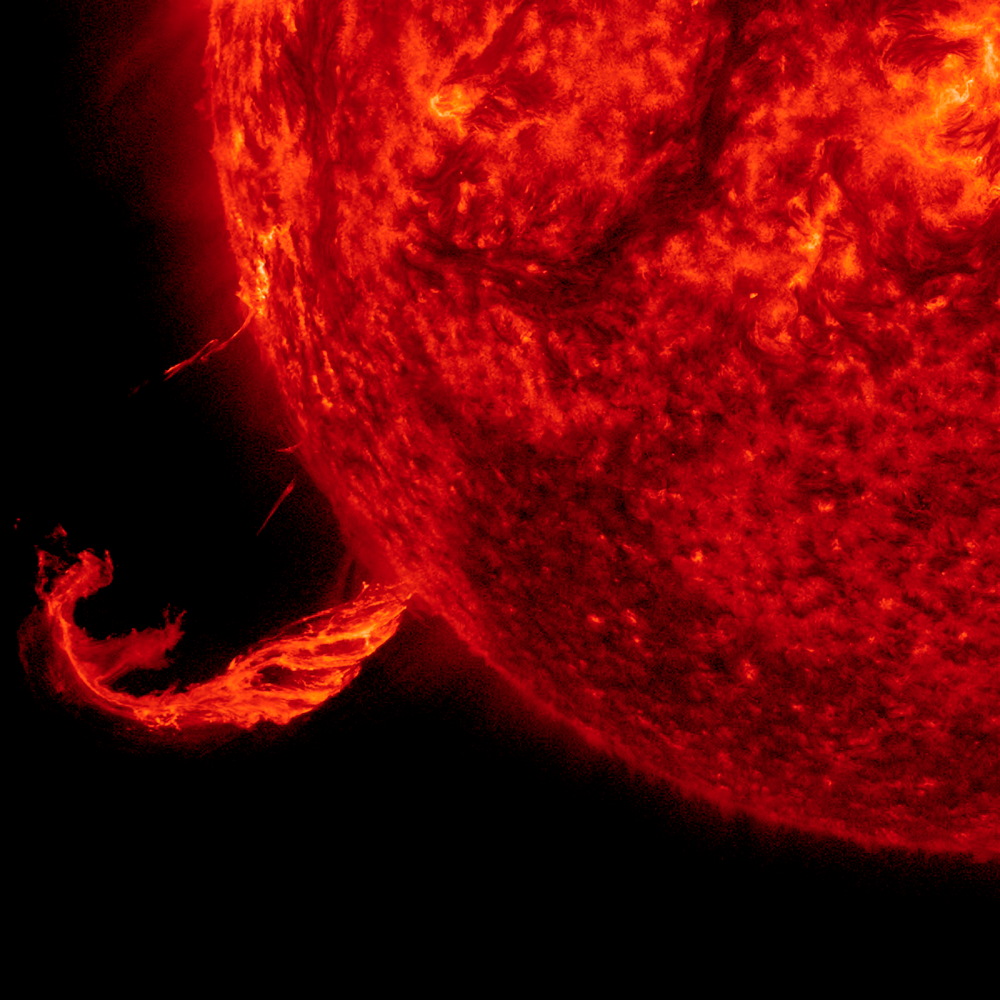

Coronal mass ejections, or CMEs, are the most impressive solar explosions. Deep within the corona (the sun's superheated atmosphere), extremely stressed magnetic fields may become unstable and erupt, sending huge bubbles of magnetized plasma into space.

If CMEs are aimed at Earth, they can have dramatic effects on the planet, boosting the radiation environment of interplanetary space and triggering geomagnetic storms. It's for this reason that space-weather forecasters track and try to predict the magnetic conditions in the lower corona. [The Sun's Wrath: Worst Solar Storms in History]

CMEs are often associated with sunspots and active regions, patches of the sun's photosphere where the internal magnetism erupts into the corona. And bright magnetic disturbances like solar flares usually precede the explosions. Sometimes, however, the sun produces a sly CME that has no relationship with active regions or any previous flaring activity; it appears to come from nowhere. The driving mechanism behind these so-called "stealth CMEs" has been a mystery — until now.

Using data from NASA's STEREO spacecraft and the NASA/European Space Agency Solar and Heliospheric Observatory (SOHO), an international team of researchers has developed a model that simulates the evolution of these mysterious eruptions, NASA officials wrote in a statement.

When compared to regular CMEs, which can shoot from the sun at incredible speeds (up to 6.5 million mph, or 10.5 million km/h), stealth CMEs are slow. They travel away from the sun at between 900,000 mph and 1.6 million mph (1.45 million km/h to 2.6 million km/h), roughly the same speed as the solar wind.

The sun's equator rotates faster than its poles, a situation known as "differential rotation." In addition, the sun is a magnetic body, with magnetism produced in the lower layers and field lines popping through the photosphere and traveling out into space. So, the star's differential rotation greatly influences its magnetic field.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers simulated the magnetic field lines that reach high into the corona and found that, because of this differential rotation, the lines eventually twist and cross one another, creating magnetic knots, like elastic bands being stretched and slowly twisted. With huge amounts of magnetic energy causing these lines to knot, they eventually pinch off (via a mechanism known as magnetic reconnection), and a "stealth" CME is quietly launched. The researchers said that enough energy is produced roughly every two weeks in the sun's atmosphere to produce stealth CMEs.

This all happens without any dramatic eruption or solar flare — just twisted magnetic field lines that pinch off and carry magnetic bubbles of plasma out of the corona, the researchers said.

Understanding how CMEs are generated is of great importance to space-weather forecasters. When these bubbles of magnetized plasma collide with Earth's magnetosphere, they can spawn powerful geomagnetic storms with the potential to seriously affect today's high-tech society. Such storms can knock power grids off-line, for example, potentially causing massive economic damage.

The new study was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

Follow Ian O'Neill @astroengine. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Ian O'Neill is a media relations specialist at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California. Prior to joining JPL, he served as editor for the Astronomical Society of the Pacific‘s Mercury magazine and Mercury Online and contributed articles to a number of other publications, including Space.com, Space.com, Live Science, HISTORY.com, Scientific American. Ian holds a Ph.D in solar physics and a master's degree in planetary and space physics.