Artist's Stunning New Exhibit Celebrates Harvard's 'Hidden' Female Astronomers

Visual artist Lia Halloran's newest exhibit, "Your Body is a Space That Sees," features large-scale paintings of astronomical objects that were photographed and catalogued by women working at the Harvard Observatory in the late 1800s.

Those women, along with their male colleagues, took thousands of photographs, catalogued and characterized the cosmic objects therein, and changed the landscape of space science. Despite the impact their work had on the world, those women were left out of history for many decades, a fate suffered by many female scientists that is now being somewhat remedied.

Halloran's exhibit is partly about remembering those forgotten histories. It's a reminder that these women existed; that they took up physical space while they also literally uncovered new territory in outer space. [Walk Through "Your Body is a Space That Sees" Exhibit (Photos)]

"It's almost like a roll call; it's like saying they were there," Halloran told Space.com at the Luis De Jesus Los Angeles art gallery, where the work was previously on display. "This experience of the history of astronomy is theirs, is ours, is yours, and it is about kind of a physical experience. It's not just something that's at a distance."

Those women may be the "your" in the title of Halloran's exhibit — "Your Body is a Space That Sees" — in whcih case, is the title spoken by the universe? Or is it the women who are talking to the current generation, calling on them to remember forgotten histories? Either way, the title calls out to the people who view Halloran's works; they are also bodies that fill a space as they observe the world around them. Observing the natural world requires a person's physical presence — someone has to look through the telescope and photograph the sky. Those physical acts are what begin to illuminate the conceptual landscape; to identify new islands in a vast, unexplored ocean of knowledge.

Harvard Computers

The Harvard College Observatory's Astronomical Photographic Plate Collection contains over 500,000 photographs of sections of the night sky, captured by astronomers between 1882 and 1992. A large portion of those photographs were taken by female astronomers who worked at the observatory in the last 1800s. Led by astronomer Edward Charles Pickering, the women were at one point given the derogatory group title "Pickering's Harem." Later, the nickname changed to the "Harvard Computers," a name created at a time when computers were people and not machines.

The work of the Harvard Computers and some of the group's most influential members is detailed in the book "The Glass Universe: How the Ladies of the Harvard Observatory Took the Measure of the Stars" (Viking, 2016) by Dava Sobel. With a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, Halloran visited Harvard and received access to the photographic plate collection around the time that Sobel was investigating the history of the people who created it. Halloran said she and Sobel began conversing as they both dug through the plate collection and the stories surrounding it.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

There were three particularly influential astronomers who came out of this Harvard group: Henrietta Swan Leavitt, who figured out a way to measure distances to far-off objects and laid the groundwork for Edwin Hubble to discover that the universe is expanding; Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, who showed that hydrogen is by far the most common element in the universe; and Annie Jump Cannon, who came up with a classification system for stars that is still used today.

But Halloran said the works are meant to reflect the entire history of female astronomers, including Hypatia, an astronomer who lived in Greece around A.D. 415, and Jocelyn Bell Burnell, who identified the first pulsar but did not share the Nobel Prize in physics that was awarded for that discovery.

Your Body is a Space That Sees: The Magellanic Cloud from Lia Halloran on Vimeo.

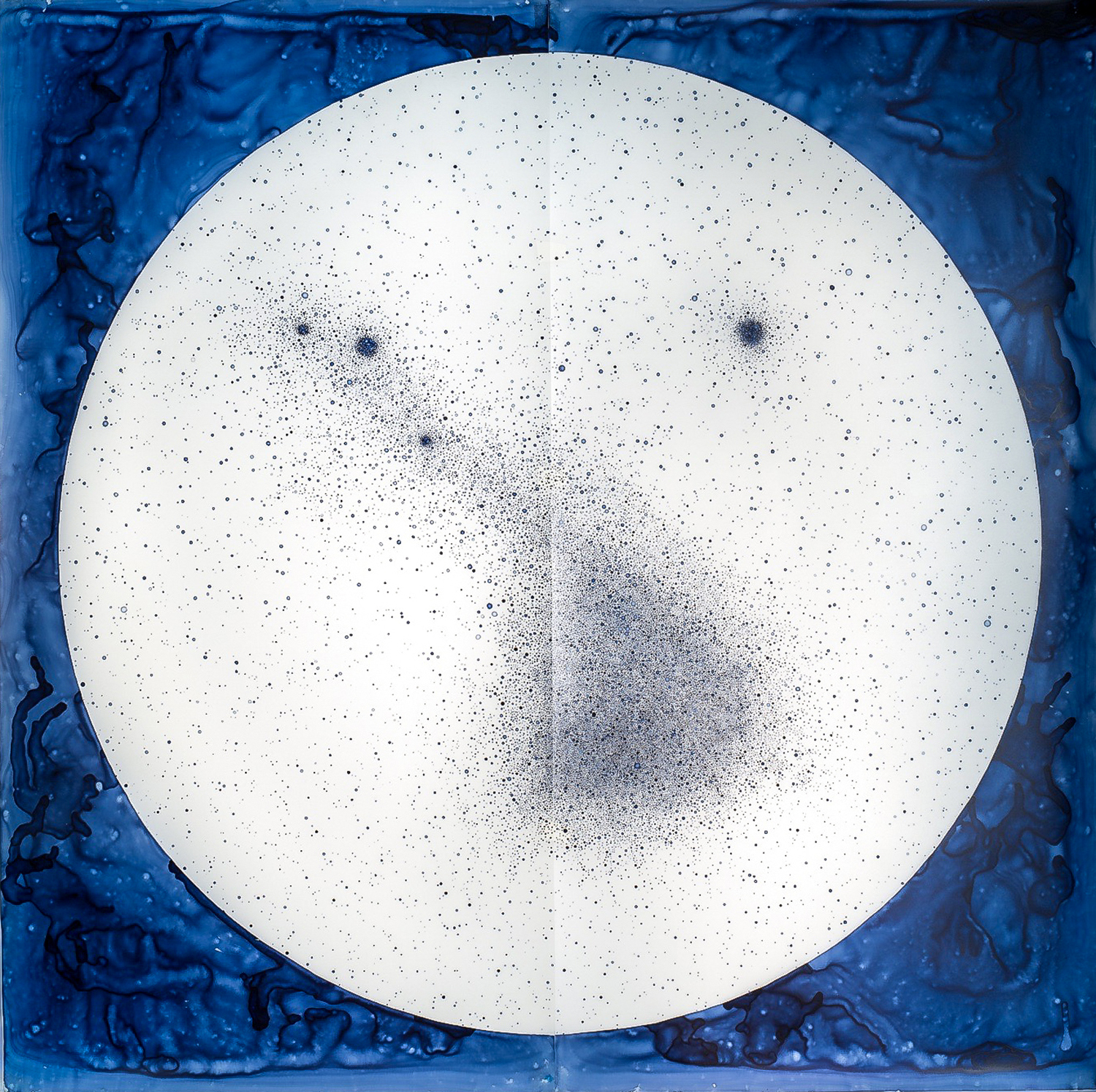

For the exhibit, Halloran selected a few plates created by members of the Harvard Computers, and did paintings of these photographs. At the gallery, Halloran showed me one of the pieces that depicts the Small Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf galaxy that orbits the Milky Way. Halloran painted hundreds of dots representing stars.

"As much as I can, I try to represent the [stellar] density," she said. "I'm not gridding it out, so if someone were to compare this with the actual image, they wouldn't find the exact number of stars [in the painting], but the density would be equivalent."

Halloran uses a type of paint that is "highly volatile," meaning it doesn't settle on the paper until the liquid in it evaporates. The effect is similar to how coffee rings dry on paper — the solids that float around in the liquid move to the outer edge of the ring, so that edge is usually darker than the inner edge.

Similarly, in Halloran's paintings, a single dot of the paint isn't a solid circle; instead, the coloring moves to the outside of the dot, creating an ombré effect all by itself. Broad, sweeping brush strokes around the edges of the panting look like the curling patterns of a gas cloud or smoke rising from a fire. These monochrome paintings are simpler versions of actual telescopic images, and the works capture the serenity of a star-filled sky and the fluid movement of cosmic structures. They may inspire a Zen-like trance in the observer.

But many of the pieces in the gallery are not just paintings; creating them involves another, much more complicated step. In the gallery, Halloran and I stand before two square pieces that both show a dense cluster of stars. One of them looks as though she used blue paint on white paper, while the other looks as though it was done with white paint on blue paper. Halloran is pointing to one and then the other, saying, "This is that." I think she must mean she's painted the same object twice, but after a few confused minutes I realize she's being literal. The piece that looks as though it was done with blue paint is actually a negative of the other painting.

To achieve this effect, Halloran did her original paintings on a semitransparent paper, which was then placed on top of watercolor paper inside a darkroom, and brushed over with a light-sensitive paint, a process called cyanotyping. When the sandwiched works are brought out of the darkroom and into the light, the light-sensitive paint creates a negative of the original painting, so that where the original was white the new one is dark, hence the new pieces looking like photo negatives of the originals. (In the past, cyanotyping was used to make copies of drawings.) The video above shows how Halloran and colleagues carried out this process.

Halloran, who is also an assistant professor of art at Chapman University in Orange County, assures me I'm not the only person who didn't immediately understand the connection between these pieces. But that's part of engaging her audience, she told me; it's her way of pushing them to more actively engage with the works, and to "have an experience."

"I like that you look at this and you don’t totally know what you're looking at," she said. "I like that there's something that makes you stay a little longer. You have to explore a little bit, to dig deep, to get in there. And that can be frustrating for the viewer. But I want them to have to have a dedicated look, and take time. [The art works] evolve and they give a little more the longer you take with them."

Another way that the pieces engage with the viewer is how they are framed: the starry landscapes are bordered by round frames, which give the impression that the viewer is looking down the tube of a telescope — it’s a reminder that the viewer's body occupies a space that sees these starry scenes. Halloran and I walk over to one of the largest pieces in the exhibit, which has a horizontal oval frame.

"When I hung this up in my studio the first time … I was like, 'Oh my gosh, I'm in a spaceship and I'm looking through this porthole!'" she said. "I didn't intend for that. But they become experiential and not just a large version of another image."

Some of the more vertically oriented oval frames even look like mirrors. Either way, they highlight the act of observation, not just by long-dead astronomers but by the people standing in the gallery.

A gift to astronomers

The cyanotyping that Halloran uses to create her works is similar to how photographs are developed, and serves as one more link to the Harvard Computers. The photographic plates are extremely fragile and would have been somewhat labor-intensive to make, but they allowed astronomers of the day to study a huge number of night-sky objects in detail, and to catalogue and characterize them without having to look into a telescope.

"It was really important that to me that, these aren't just images from history, but the process itself sort of reflects that history," Halloran said.

The Harvard plate collection has also provided a historical record of cosmic objects unlike anything else that exists in astronomy. Astronomers in the 21st century have used the plates to look for objects that have moved across the sky in the last 100 years or so. The background stars are so distant that even over the course of a century, they will appear to be in the same place relative to each other. But nearer objects like asteroids or objects in the Kuiper Belt (the region of the solar system beyond Neptune) could move relative to those background stars over decades or centuries; therefore, by comparing two images of the same patch of sky, taken 50 or 100 years apart, astronomers could identify those moving, nearby bodies.

In another 100 years, scientists will have plenty of digitized sky observations to comb through, but for now, the glass plates are a rare gift to modern astronomers. Halloran thinks that's a contribution that's worth remembering, and worth honoring through art.

You can see more of Halloran's work on her website, or follow her studio on Instagram at @halloranstudio.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter