How Hot Were the Oceans When Life First Evolved?

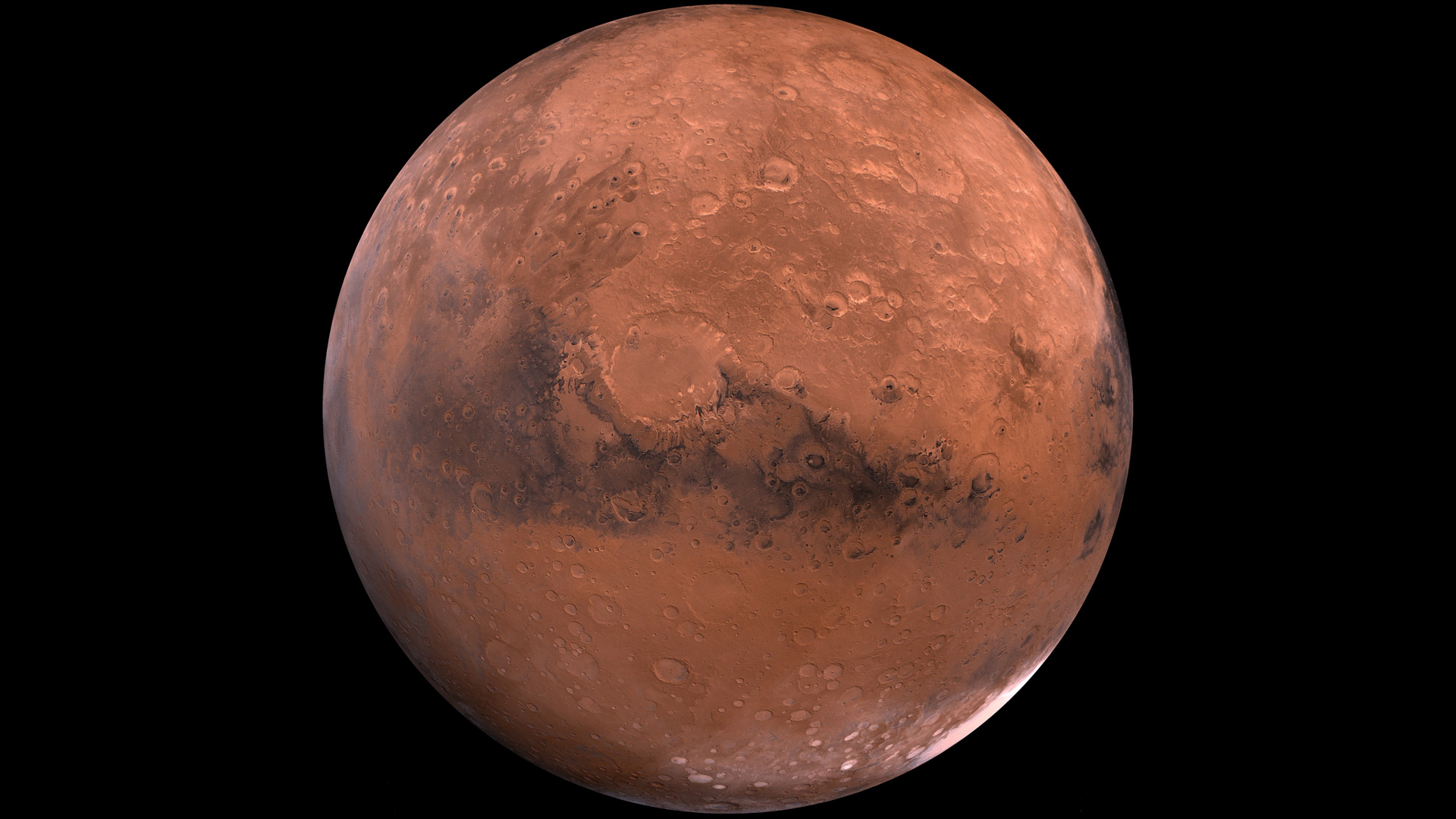

We know little about Earth's surface temperatures for the first 4 billion years or so of its history. This presents a limitation into research of life's origins on Earth and how it might arise on distant worlds.

Now researchers suggest that by resurrecting ancient enzymes they could estimate the temperatures in which these organisms likely evolved billions of years ago. The scientists recently published their findings in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

"We need a better understanding of not only how life first evolved on Earth, but how life and the Earth's environment co-evolved over billions of years of geological history," said lead author Amanda Garcia, a paleogeobiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles. "A similar co-evolution seems certain to be the case for any life elsewhere in the Universe." [Ancient Earth: Pummeled, Cracked and Oozing Magma (Visualization)]

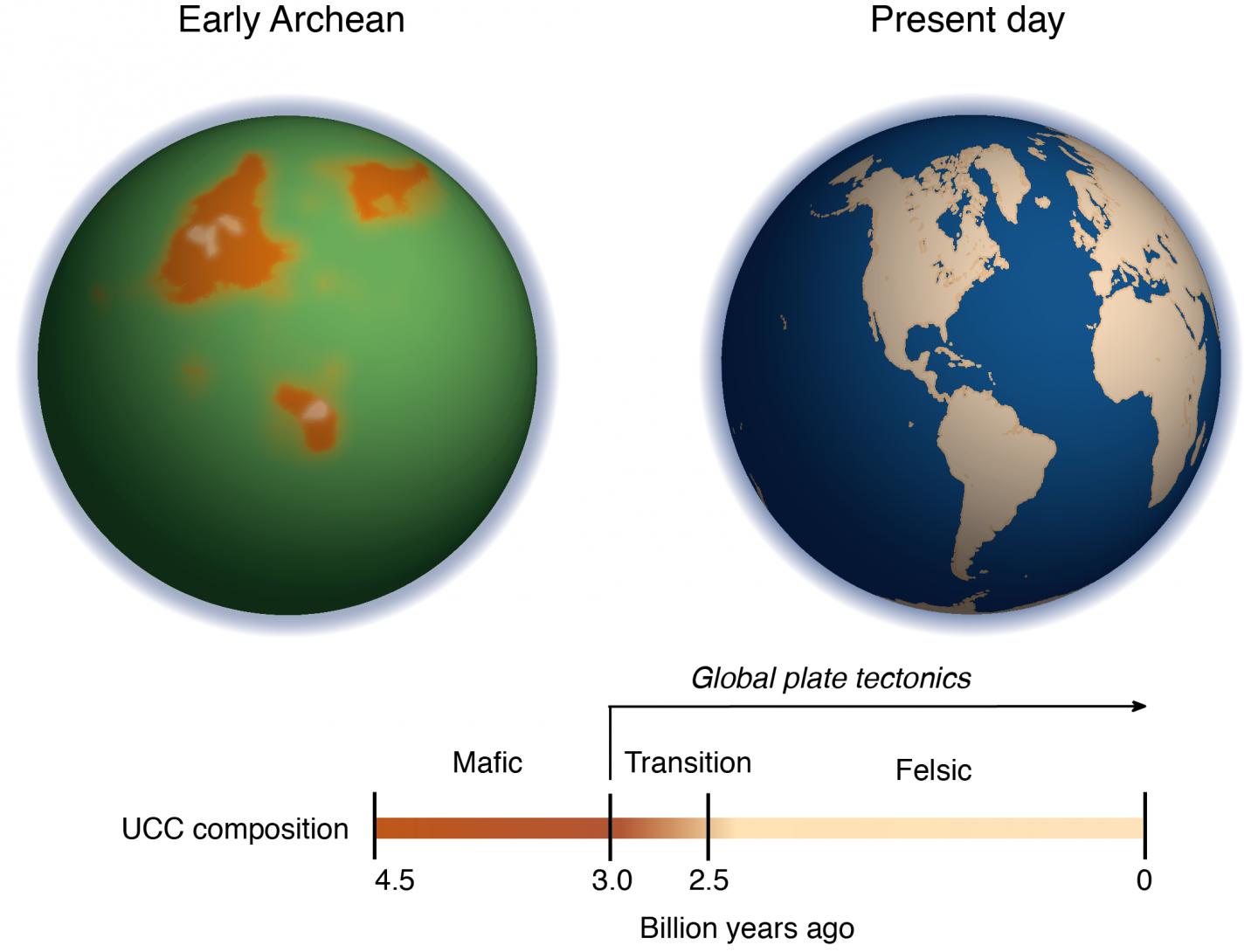

Garcia and her colleagues focused on the history of Earth's surface temperatures. Rocks offer many clues to deduce temperatures over the last 550 million years in the Phanerozoic Era, when complex, multicellular life took off, including that of humans. However, few such "paleo-thermometers" exist for the earlier Precambrian Era, spanning the Earth's formation 4.6 billion years ago and the rise of life.

Earlier geological evidence has suggested that 3.5 billion years ago, during the Archean Eon, the oceans were 131 degrees to 185 degrees F (55 degrees to 85 degrees C). They cooled dramatically to current average temperatures of 59 degrees F (15 degrees C). Scientists made these estimates by examining oxygen and silicon isotopes in marine rocks. Quartz-rich rocks in the seabed, known as cherts, have higher levels of the heavier oxygen-18 and silicon-30 isotopes as the seawater gets colder. In principle, the ratio of heavier to lighter oxygen and silicon isotopes can shed light on ancient temperatures.

But such paleo-thermometers do not adequately take into account how these rocks or the ocean might have changed over the course of billions of years. Perhaps the isotopic ratios in seawater varied over time in response to physical or chemical alterations, such as water flows off the land or from hydrothermal vents.

Given the uncertainties, Garcia and her colleagues sought an independent measurement of seawater temperatures in the Precambrian that centers on the behavior of biological molecules. The scientists examined an enzyme known as nucleoside diphosphate kinase (NDK), which helps manipulate the building blocks of DNA and RNA, as well as many other roles. Versions of this protein are found in virtually all living organisms, and were likely vital to many extinct organisms as well. Previous research found a correlation between the optimal temperatures of protein stability and an organism's growth.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

By comparing the molecular sequences of versions of NDK in a variety of contemporary species, researchers can reconstruct the versions of NDK that might have been present in their common ancestors. By synthesizing these reconstructions, scientists can experimentally test these "resurrected" ancient proteins to find the temperature that stabilizes the protein and deduce from that the likely temperature that supported the ancient organism.

Scientists estimate when ancient enzymes might have existed by looking at their closest living relatives of their host organism. The greater the number of differences in the genetic sequences of these relatives, the longer ago their last common relative likely lived. Scientists use these differences to gauge the age of biomolecules such as the reconstructions of NDK. [The Strangest Alien Planets (Gallery)]

Previous research had reconstructed ancient enzymes to deduce past temperatures, but some of these enzymes may have come from organisms that lived in unusually hot environments, such as deep-sea hydrothermal vents, which would not be representative of the wider ocean. Instead, Garcia and her colleagues sought to reconstruct NDK from land plants and photosynthetic bacteria living in the upper sunlit depths of oceans, presumably far away from boiling hot springs.

Their research suggests that Earth's surface cooled from roughly 167 degrees F (75 degrees C) about 3 billion years ago to roughly 95 degrees (35 degrees F) about 420 million years ago. These findings are consistent with previous geological and enzyme-based results.

Garcia said such a dramatic cooling is hard to fathom, emphasizing how scientists need to remember how different conditions were in the past when figuring out how life evolved over time.

"It requires a lot of effort to envision a world that does not seem to fit with the common sense of our current Earth conditions."

Future research could reconstruct versions of NDK from more organisms, as well as other enzymes, giving more evidence to support the method. Such research could help "in solving big questions about the early evolution of life and Earth's environment," she said.

The participation of study co-author J. William Schopf, founder of the Center for the Study of Evolution and the Origin of Life at the University of California, Los Angeles, was supported by his membership in the NASA Astrobiology Institute's Wisconsin Astrobiology Research Consortium.

This story was provided by Astrobiology Magazine, a web-based publication sponsored by the NASA astrobiology program. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us