Ripples in Space-Time! Gravitational-Wave Observatory Detects 3rd Black Hole Merger

It's not a fluke: For the third time, scientists have detected ripples in space-time caused when two black holes circle each other at mind-bending speeds and collide.

The LIGO gravitational-wave detector spotted the space-time ripples on Jan. 4, members of the LIGO Scientific Collaboration announced today (June 1).

If this news sounds familiar, it's because this is the third black-hole collision that LIGO has detected in less than two years. These three consecutive discoveries signal to astrophysicists that mergers between black holes in this mass range are so common in the universe that LIGO may detect as many as one per day when the observatory begins operating at its full sensitivity, members of the collaboration said during a news teleconference yesterday (May 31). [How to See Space-Time Stretch - LIGO | Video]

"If we'd run for a long time and hadn't seen a third black-hole merger … we would have started scratching our heads and saying, 'Did we just get really lucky that we saw these two rare events?'" David Reitze, LIGO Laboratory executive director and a professor of physics at the California Institute of Technology, told Space.com. "Now I think we can say safely that that's not the case. I think that's exciting."

A batch of black-hole detections by LIGO could help scientists learn how black holes of this size — those with masses tens of times that of the sun, or so-called stellar-mass black holes — are born, and what causes them to come together and merge into a new, single black hole. A paper describing the new discovery includes a few clues about the spins of the original two black holes, which is an early step in learning about the environment where they formed and how they ended up colliding.

Ripples in space-time

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

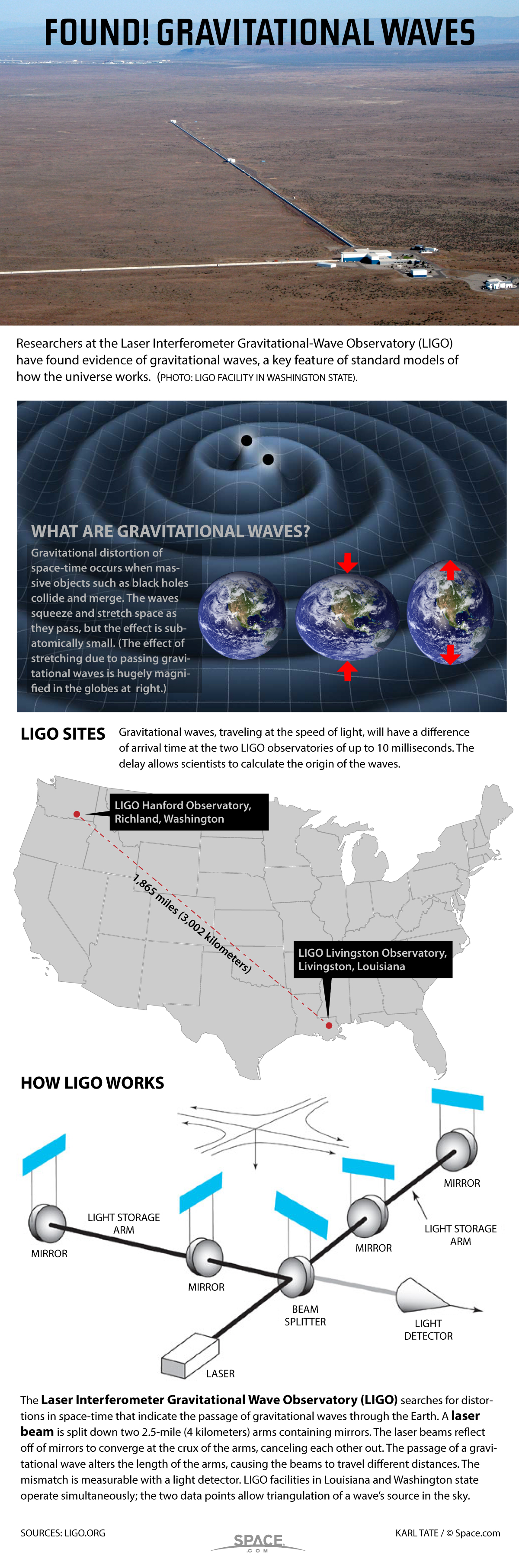

LIGO (which stands for Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory) was the first experiment in history to directly detect gravitational waves — ripples in the universal fabric known as space-time that were first predicted by Albert Einstein. The famous physicist showed that space and time are fundamentally linked, such that when space is distorted, time can either slow down or speed up.

Although LIGO first began taking data in 2002, it wasn't until the observatory underwent a major upgrade, called Advanced LIGO, that it achieved the sensitivity necessary to make a detection. The first black-hole merger spotted by LIGO was announced in February 2016; the second was announced in June 2016.

This new merger spotted by LIGO took place between one black hole with a mass about 19 times that of the sun, and another with a mass about 31 times that of the sun. Those companions combined to form a new black-hole with a mass of about 49 times that of the sun (some mass can be lost during the merger). The entire mass of that final black hole is packed into an object with a diameter of about 167 miles (270 kilometers), or about the width of the state of Massachusetts, according to the LIGO scientists.

This newly-formed black hole falls between the final masses of the black holes that LIGO previously detected, which were 62 solar masses and 21 solar masses.

The gravitational waves created by this new black hole collision had to travel across the universe for 3 billion years before they reached Earth. That means this new black hole merger occurred more than twice as far away from Earth as the first and second black hole mergers detected by LIGO. The gravitational waves from those black hole collisions traveled for 1.3 billion and 1.4 billion years to reach Earth, respectively.

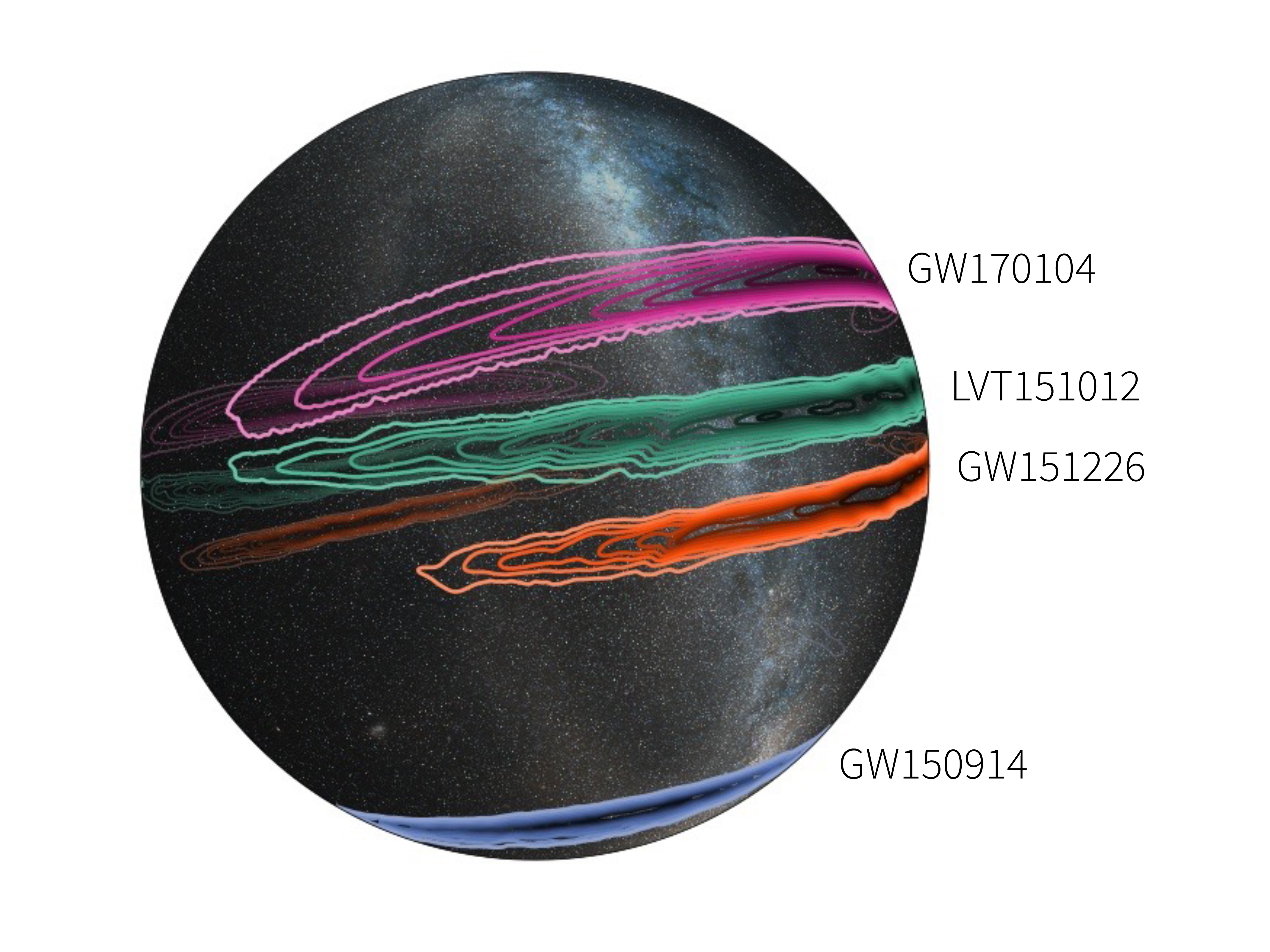

However, as with the previous two detections, the LIGO detector can't determine precisely where the newly formed black hole is located. Rather, the data only narrows down the source of the signal to an area of about 1,200 square degrees. (See the map of the sky above to see the area from which the signal could have come.)

Because black holes don't radiate any light of their own (or reflect light from other sources), they are effectively invisible to light-based telescopes, unless regular matter nearby creates a secondary source of light. Black holes with masses between 20 and 100 solar masses aren't expected to have much, if any, regular matter around them radiating light, and black holes in this mass range hadn't been observed by astronomers prior to LIGO's three discoveries.

But gravitational waves come directly from the black holes. This opens up a new realm of the universe that is visible to an instrument like LIGO, which was designed to detect gravitational waves, but invisible to other telescopes. The three mergers that LIGO detected not only confirm the existence of black holes in this mass range, but also show that they are fairly common throughout the universe, according to the collaboration members. [Images: Black Holes of the Universe]

Watch it spin

In the data from the new detection, the LIGO scientists managed to glean a little information about the spin of the two black holes. Those clues could hint at why the black holes wound up crashing into each other, LIGO collaboration members said.

Black holes spin on their axes just as the Earth, most planets and most moons do. Stellar-mass black holes are thought to form when massive stars run out of fuel and collapse. If two massive stars live in a "binary" system, they will typically spin along the same axis, like two tops spinning next to each other on the ground. When those stars become black holes, they will also spin along the same axis, researchers said in a statement from Caltech.

But if the black holes formed in different regions of a stellar cluster and come together later, they may not spin along the same axis. Those misaligned spins will slow the merger, said Laura Cadonati, the LIGO Scientific Collaboration's deputy spokesperson and an associate professor of physics at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

"In our analysis, we cannot measure spins of individual black holes very well but can tell if they're generally spinning in same direction," Cadonati said during yesterday's news teleconference. The LIGO data doesn't provide a strong ruling about whether the black-hole spins were aligned or misaligned. The authors of the new research concluded that the data "disfavors" the identical spin alignment of the black-hole axis, according to the paper, which has been accepted for publication in the journal Physical Review Letters.

"This is the first time that we have evidence that the black holes may not be aligned, giving us just a tiny hint that binary black holes may form in dense stellar clusters," Bangalore Sathyaprakash, a researcher at Pennsylvania State University and Cardiff University and one of the LIGO collaboration members who edited the new paper, said in the statement from Caltech.

Of course, black-hole mergers could arise from both scenarios. To get an idea of the most common origin story for solar-mass black-hole mergers, LIGO scientists will need more than three examples to study.

Black-hole statistics

The discovery of three stellar-mass black-hole mergers in less than two years indicates that LIGO will be seeing a lot more of these types of events, Reitze told Space.com. But three events are still not enough to know for sure exactly how frequently LIGO will begin to see these black-hole collisions once its sensitivity is increased. The optimistic estimate that Reitze and other collaboration members cite is one per day, but even the pessimistic estimates are around one per month. That means LIGO could collect data on tens to hundreds of black-hole mergers in three to five years of operations. With this collection of black-hole mergers, scientists will be able to learn about the general population rather than a few individuals.

A large collection of black holes could also provide scientists with a deeper look at Einstein's theory of general relativity. Black holes are "pure space-time," according to Reitze, meaning that while they might have formed from regular matter, their interaction with the universe has none of the properties of regular matter. Rather, the characteristics of a black hole are described entirely in terms of how its gravity warps space-time or influences other objects.

The theory of relativity predicted the existence of space-time and gravitational waves, so LIGO's detection of this phenomenon was another confirmation that the theory is accurate. But the study of black holes and gravitational waves could also reveal cracks in that theory.

For example, when light waves pass through a medium like glass, they may be slowed based on their wavelength — a process called dispersion. General relativity states that gravitational waves should not be dispersed as they travel through space, and the researchers saw no sign of dispersion in LIGO's new data.

For now, it seems, Einstein was right. But one of the most exciting things that LIGO could potentially discover is a flaw in the theory, Reitze said. Einstein's theory of gravity has withstood scrutiny for more than a century, but it also doesn't match up with the theory of quantum mechanics. The lack of an obvious connection between gravity (which generally describes the universe on very large scales) and quantum mechanics (which describes the universe on very small scales) is one of the most significant unsolved problems in physics. That problem isn't likely to go away unless it turns out there's some still-undiscovered angle to one or both of those theories.

"The question is, where does [general relativity] break down," Reitze said, and will LIGO's data on black holes provide the right laboratory for answering that question?

The detection of a gravitational-wave signal is significant for LIGO because it confirms that the experiment is "moving from novelty to real gravitational-wave science," David Shoemaker, a spokesperson for the LIGO Scientific Collaboration and a professor of physics at MIT, said during the news conference. This gravitational-wave-hunting machine has officially demonstrated its ability to illuminate a once-dark sector of the universe.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield.Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter