Turn Your Smartphone into an Astronomy Toolbox with Mobile Apps

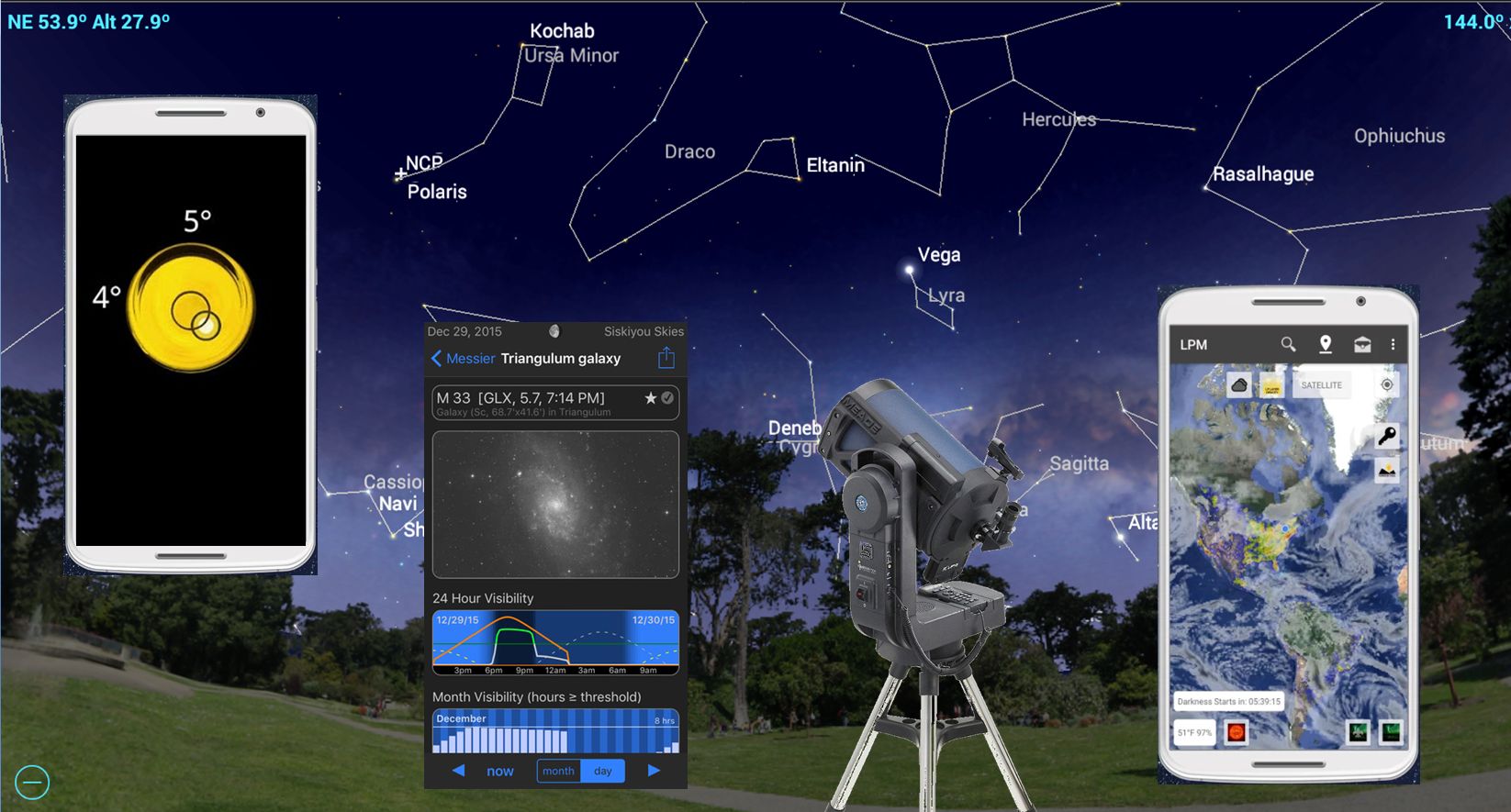

The phone in your pocket is a veritable Swiss Army knife of functionality for both casual stargazers and serious astronomers. In this edition of Mobile Astronomy, we'll look at the ways your phone, when loaded with the right apps, can enhance your astronomy hobby as you plan your observing sessions, set up your telescope, record your observations and much more.

Planning your observing session on your phone

Your phone's usefulness for astronomy starts well before you pack up your telescope or cameras and leave the house. It can help you find and navigate to an observing site. It also lets you check the location's weather forecast to decide whether to make the drive.

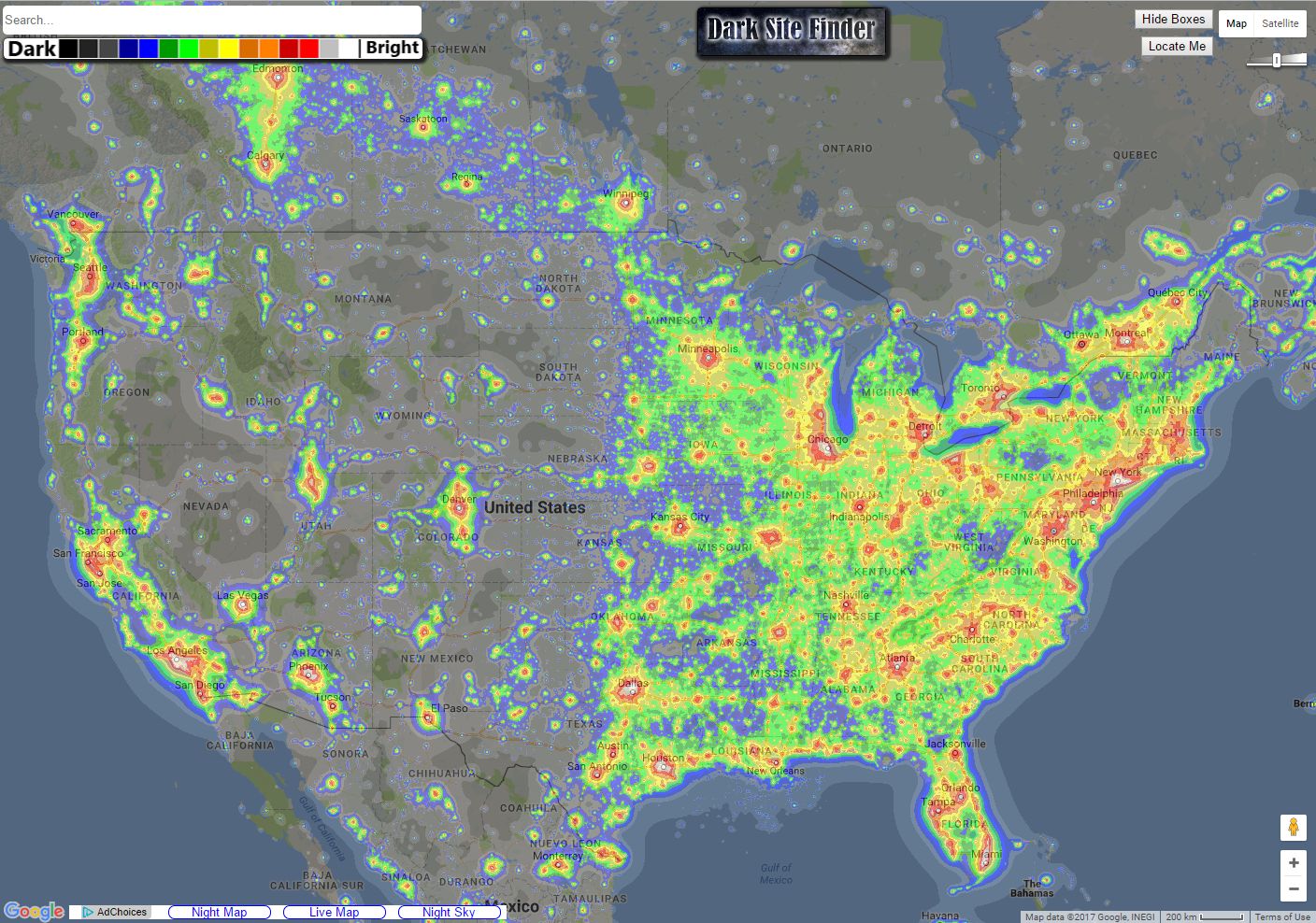

When seeking a new dark observing site, I like to consult light pollution maps. The Dark Site Finder website uses a Google Maps interface overlaid with color-coded light pollution data. White, red and orange tones indicate extremely light-polluted areas that are poor for skywatching. Yellow means moderate light pollution, and green through black indicate the darkest skies. You can pan and zoom in and out on the map to find darker skies within a reasonable driving distance (or check the skies at your upcoming vacation spot). [A Planet Skywatching Guide for 2017: When, Where & How to See The Planets]

State and national parks are usually good bets for pristine skies, but you should check their after-dark policies for visitors. For privately held property, you must get permission from the owner (preferably during the daytime). They'll often be happy to host you and a few friends if you are quiet, leave the area as you found it and offer to show them a few objects.

If you are traveling to a remote location, be sure to file a "flight plan" with loved ones, and use your phone to confirm that you've arrived safely. Your stock Maps app will navigate you to a new observing site. But consider downloading the area as an offline map while you're still home, in case the cell coverage is spotty or nonexistent on-site.

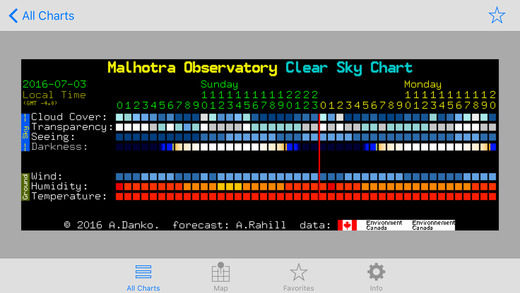

Your usual weather forecasting app will tell you whether it's cloudy or clear, as well as the temperature and the chance of rain. But for observing, other factors are important, too. How steady will the air be? Rough air makes stars twinkle and blurs the view. Will the air be heavy with moisture and hazy, or dry and transparent? Will your telescope or camera become coated with dew?

The free Clear Outside app for Android and iOS provides nearly everything a skywatcher will need to know about the observing conditions. In a graphical format, it shows predicted hourly cloud-cover values, visibility (i.e., sky transparency), and the likelihood of fog, rain, wind and frost. It indicates when the sky will be fully dark after sunset and before sunrise, the contribution of moonlight, and even when the International Space Station will fly overhead!

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Other favorites — the free Clear Sky Droid app for Android and iCSC: Clear Sky Chart Viewer app for iOS —use the popular Clear Dark Sky website. Both let you select from a list of weather station sites throughout North America. They provide an hourly breakdown, in a graphical format, of the cloud cover, transparency, seeing, darkness, wind, humidity and temperature for the next 48 hours. Note that the information is based on future weather models that are updated only about twice per day, not in real time.

The free Astronomy Tools Night Sky app for Android does even more than weather. It details cloud cover, sends aurora and meteor shower alerts, includes built-in light pollution maps, describes moon position, and more. The paid Scope Nights: Astronomy Weather and Dark Sky Map for iOS analyzes the weather and rates the stargazing up to 10 nights in advance, issues alerts when conditions are great, and more. For real-time weather conditions, look at the NOAA Weather Radar app for Android and iOS. It provides animated satellite imagery of cloud cover and precipitation for most of the world.

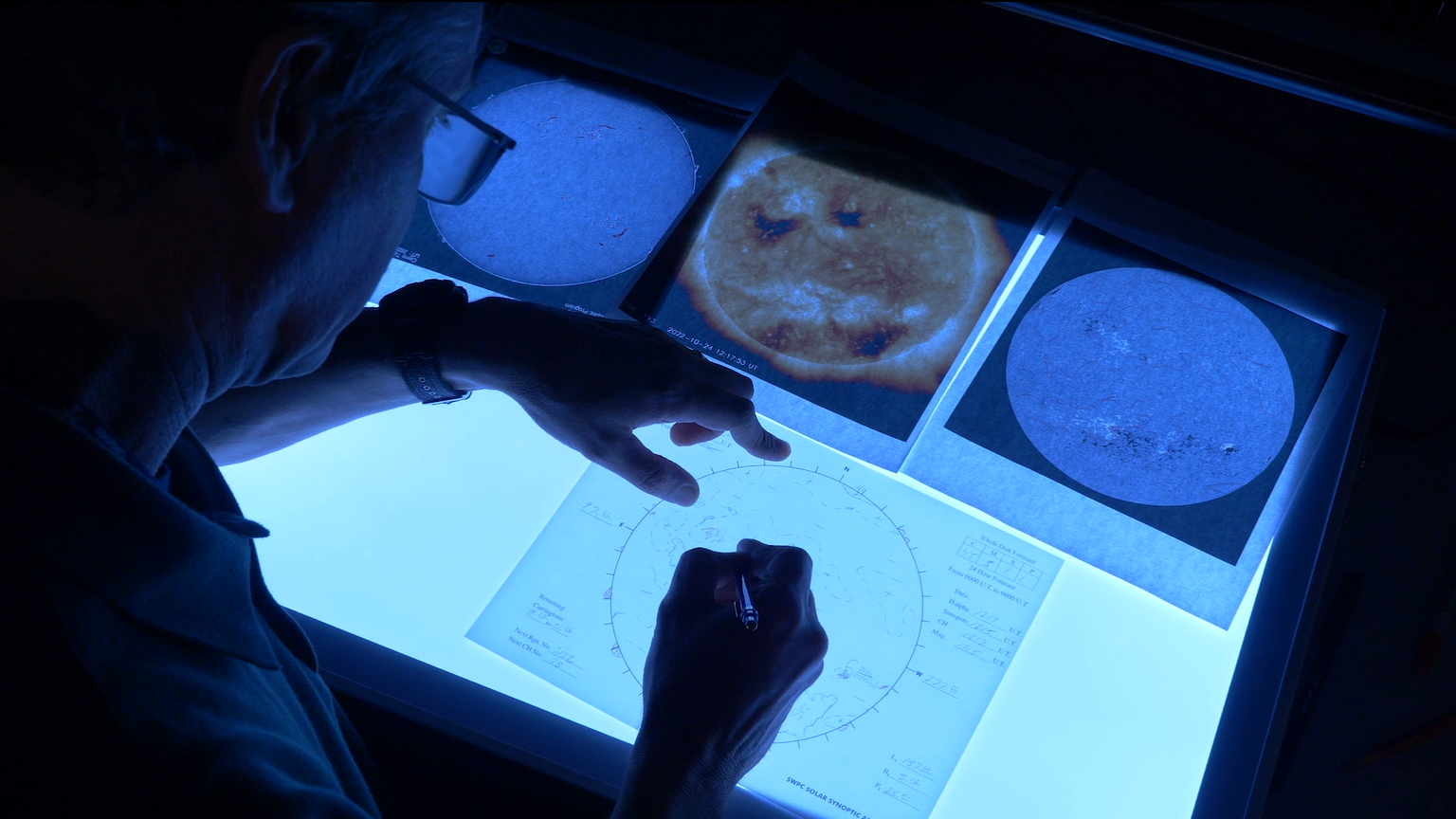

Using your phone to set up your telescope

Telescopes with equatorial mounts, and most motorized GoTo and tracking systems, need to be set up level and aligned with the Earth's polar axis. The better they are aligned, the more accurate the tracking and GoTos will be. Long-exposure astrophotographs will be sharper, too. Here's how your phone can help.

At night, the polestar (Polaris, or the North Star) can be used for alignment. But if you are setting up a tracking telescope to observe the sun or a nighttime scope before it's dark enough to see Polaris — or if you are in the Southern Hemisphere, where there is no polestar to align on — it helps to have a compass app handy. There are plenty of free ones. You need to set up based on true north, not magnetic north. The better compass apps will include what's called a declination correction for this.

To level the telescope tripod, install a bubble level app, and simply rest your phone on the eyepiece tray or another part of the mount. Find an app that levels in two directions simultaneously, such as a circular bubble level, and that buzzes when levelness is achieved so that you can adjust the tripod legs without needing to see the phone's display.

The polar (or right ascension) axis of equatorial mounts need to be tilted at the angle equal to your latitude on Earth. Pick a bubble level app such as Bubble for Android or Bubble Level for iPhone and iPad that has a digital readout of the tilt. Then, use it to check the angle of the telescope's tube, or the polar axis directly. (For mounts that have counterweight shafts, you can hold the phone against it. The shaft should be tilted at 90 degrees minus your latitude.)

Remember that your device's compass and gyroscope need to be calibrated properly. Bubble level apps have options to zero the reading when your phone is resting on a horizontal surface. Compass apps will have instructions to sweep your phone in a pattern that corrects the magnetic readings. Be sure to avoid standing near metal objects, such as your car, when doing this. Another good option is to check your phone's tilt and compass readings on a telescope that you know is already aligned, using the polestar.

Finally, computerized telescope mounts also need to know the correct time and observing location so that they can calculate where the stars are. Your phone's GPS sensor measures these, but there isn't always an easy way to access the values. I find that a good hiking or navigating app, such as DS Software's free Polaris GPS Navigation for Android, offers everything you'll need, including a compass. [June Full Moon 2017: How to See the Strawberry Minimoon]

Choosing and recording astronomical objects

In past editions of Mobile Astronomy, we've covered the many ways in which astronomy sky chart apps can help you identify things in the sky and locate particular objects. They also provide many details about these sights. Many astronomy enthusiasts like to keep a record, or observing log, of what they have seen over the years. Some chase down certain objects in order to earn observing certificates from astronomy clubs or societies, and some prefer to observe certain types of objects. (I like planetary nebulas!) There are also specific types of observations, such as variable star brightness estimates, that you can submit as a citizen scientist.

SkySafari 5, Night Sky Tools and other apps include additional functionality for creating observing lists. Set the app to the date and time you'll be observing, and use the search function to find the objects of interest. Alternatively, you might need to view a particular target in an observing certificate program. The app can show you the best time to see it.

To make an observing list in SkySafari 5, open the Search menu, scroll to the bottom and tap the Create New Observing List option. You'll be prompted for a name. Exit this menu, and select a celestial object by tapping it on the display. Tap the Info icon. (You can also do this by using the object's name in the search menu.) In the lower right of the information panel, tap the More… icon. A dialog box will appear. Select Add to Observing List, and tap the list you created. Later, you can sort, edit and manage the objects in the list. You can also make multiple lists. There are also dozens of publicly available observing lists you can import from the Online Repository.

Traditionally, observations were recorded in a paper logbook. But your phone makes this far easier. You can log a description of an object using the voice recorder on your phone as you peer into the eyepiece. You can type into a note-taking app. Or, better yet, you can use an astronomy app with logging functionality.

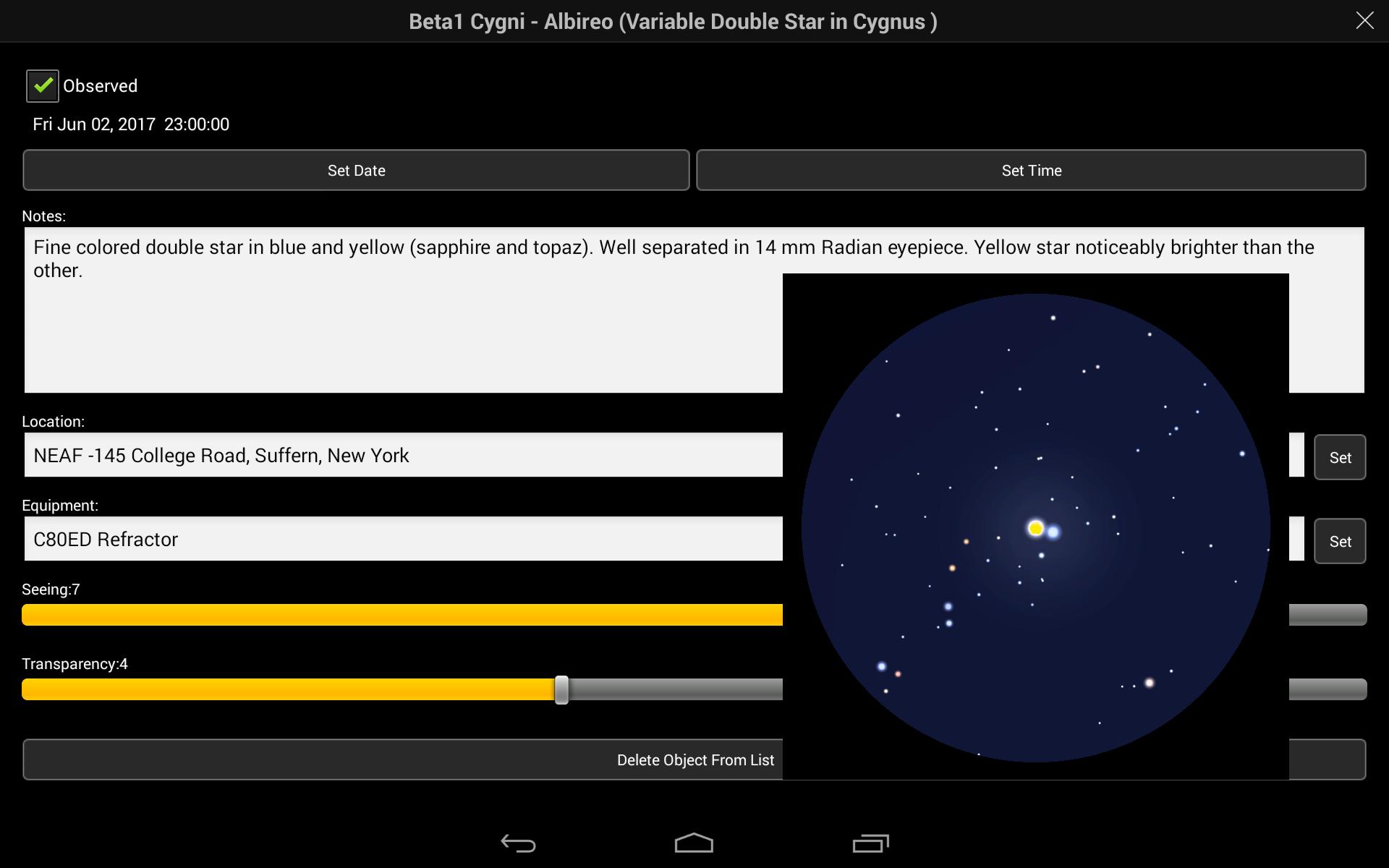

For instance, you can log your observations of your observing-list objects in the SkySafari 5 app. In the object's information page, tap More… and select Create New Observation. The app will launch a form where you can enter the date, time and location (some are autofilled), your notes, the equipment you used, and the seeing and transparency rating for the night. The Night Sky Tools app for Android provides similar functionalities, and even allows for filters or cameras.

Finally, the Observer Pro — Astronomy Planner for iOS app lets you plan your sessions, make observing lists and log observations. It even lets you map the horizon profile of your observing site to determine when objects will be visible — for example, high enough to clear the neighbor's garage roof — all for about $10.

But wait, there's more your phone can do…

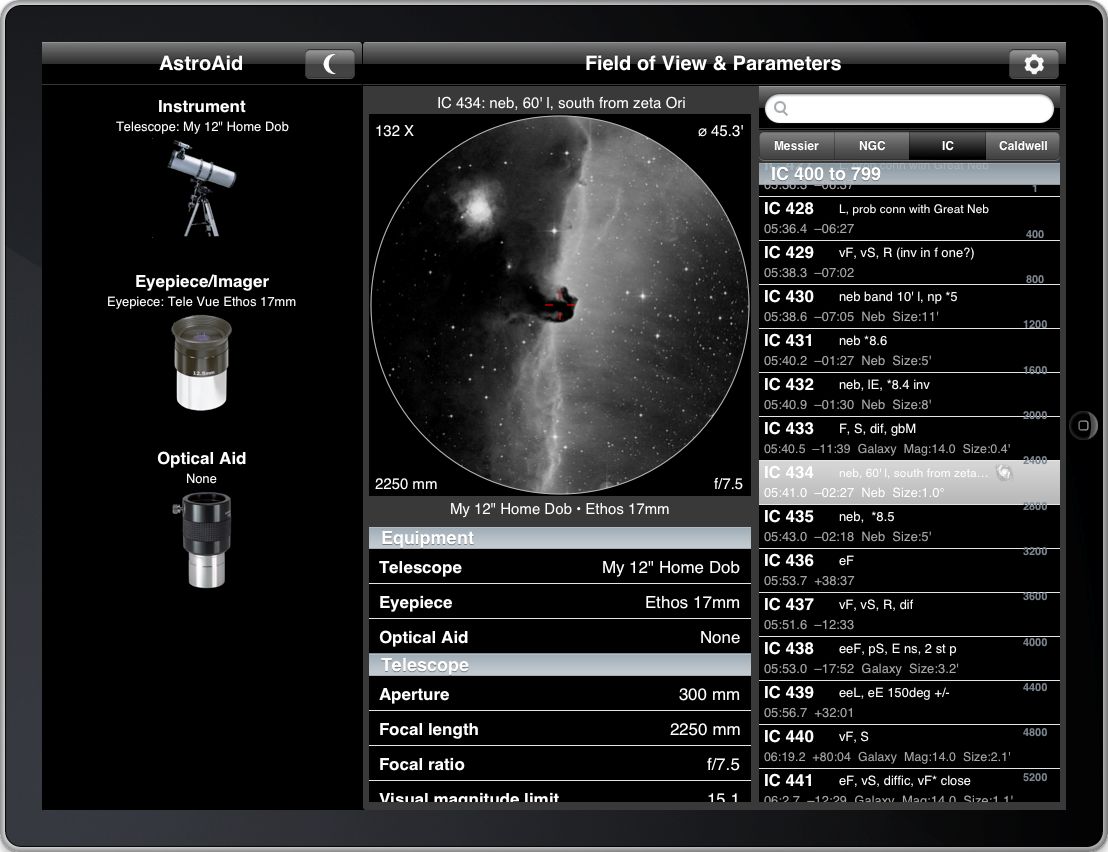

Telescope owners find it helpful to know the magnifications and fields of view produced by their various eyepieces. A good tip is to calculate the values and save them in a document on the phone. Or, use an app designed just for that! The AstroAid app for iOS lets you select from preloaded commercial telescopes, eyepieces and accessories. Then, it can calculate all of the values, and even generate previews for many of the major deep-sky objects.

Everyone approaches astronomy their own way. When I'm not chatting with folks, I like to listen to music when I observe, and my smartphone is loaded with plenty of inspiring tracks for that. If you do the same, be sure you aren't bothering your fellow observers or disturbing sleepers in the middle of the night. For safety, avoid using earbuds when observing alone in an unfamiliar place.

You don't need to be an expert astrophotographer to capture a memento of your night under the stars. In How to Snap Awesome Photos of Night-Sky Objects with Your Smartphone, we covered how to capture images of astronomical targets using your phone. Astronomy outreach and education events are perfect opportunities to engage students and the public in astronomy by sharing their excitement and images on social media. And, hey, why not tweet or text an invitation to your next observing session? We'd love to join you!

If you have found other ways to use your phone for astronomy, feel free to send me a note or share them in the comments. In a future edition of Mobile Astronomy, we'll cover how to wirelessly control your telescope with your phone, highlight some early summer celestial treats, and more. Until then, keep looking up!

Editor's note: Chris Vaughan is an astronomy public outreach and education specialist, and operator of the historic 1.88-meter David Dunlap Observatory telescope. You can reach him via email, and follow him on Twitter @astrogeoguy, as well as on Facebook and Tumblr.

This article was provided by Simulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of the SkySafari app for Android and iOS. Follow SkySafari on Twitter @SkySafariAstro. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Chris Vaughan, aka @astrogeoguy, is an award-winning astronomer and Earth scientist with Astrogeo.ca, based near Toronto, Canada. He is a member of the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada and hosts their Insider's Guide to the Galaxy webcasts on YouTube. An avid visual astronomer, Chris operates the historic 74˝ telescope at the David Dunlap Observatory. He frequently organizes local star parties and solar astronomy sessions, and regularly delivers presentations about astronomy and Earth and planetary science, to students and the public in his Digital Starlab portable planetarium. His weekly Astronomy Skylights blog at www.AstroGeo.ca is enjoyed by readers worldwide. He is a regular contributor to SkyNews magazine, writes the monthly Night Sky Calendar for Space.com in cooperation with Simulation Curriculum, the creators of Starry Night and SkySafari, and content for several popular astronomy apps. His book "110 Things to See with a Telescope", was released in 2021.