Apollo Astronaut Shares Recollections 45 Years After Moon Landing (Exclusive Interview)

He landed on the moon nearly half a century ago, but Apollo 16 astronaut Charlie Duke vividly remembers the view while standing on the Descartes highlands.

"There was a contrast between the black sky of the moon and the brightness of the lunar surface. It was an incredible contrast," Duke said in an exclusive interview with Space.com.

"Unfortunately, where we stood [on the moon], the Earth was directly overhead," he added. "You couldn't see it in your Apollo spacesuit. The helmet is like a fishbowl, and looking straight up, you were looking at the opaque side of your helmet. We did see it [Earth], however, in lunar orbit as we came around the [moon's] back side, and it was very dramatic." [Apollo 16: NASA's 5th Moon Landing with Astronauts in Pictures]

Duke will appear at the San Diego Air & Space Museum today (June 7) at an event to celebrate the 45th anniversary of Apollo 16, which took place in April 1972. Other expected attendees include Walt Cunningham (Apollo 7), Fred Haise (Apollo 13), Al Worden (Apollo 15) and Gerry Griffin (lead flight director for Apollo 12, 15 and 17).

To coincide with the anniversary, Duke, 81, has been working with New York-based communications consultancy Chaco to create a new website for public engagement, which will soon be available at CharlieDuke.com.

"These anniversaries, as we get closer to the 50th of [the first moon landing] Apollo 11 … help us to recall the adventure of it and the excitement of it," Duke said. "They help motivate the young generation to, as I say, aim high or dream big. I like to participate in these kinds of things, so hopefully, we can change one life to motivate a kid to stimulate them to study in science and engineering."

Lunar geology work

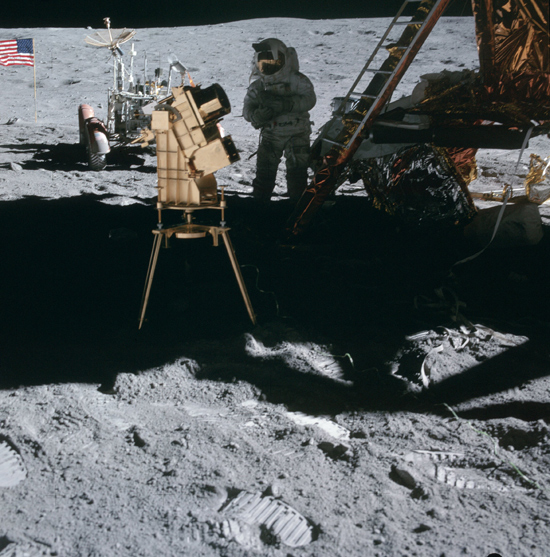

Apollo 16 was the fifth mission to land humans on the moon, but the later arrival to the moon gave the crew an advantage: the opportunity to do a more ambitious mission. The astronauts on Apollo 11, 12 and 14 did all of their exploring on foot. (Apollo 13 had a similar mission scope, but its astronauts abandoned the moon landing because of an emergency.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Starting with Apollo 15, the rest of the lunar missions used rovers to do more thorough exploring. These later missions (which included Apollo 15, 16 and 17) also had its astronauts explore the lunar highlands, which had a greater variety of rocks to sample.

Duke, who was the lunar module pilot, and his commander, John Young, had spent so much time on Earth studying geology that Duke estimates his crew had the equivalent of a master's degree in geology experience. (Command module pilot Ken Mattingly also had geology training, but he used it for orbital observations; he stayed in lunar orbit while Young and Duke landed on the moon in a separate vehicle.)

Duke said one of his most exciting science moments during the flight was finding out that the rocks in the Descartes highlands were not volcanic as scientists had expected. Instead, they were breccias — fragments of multiple lunar impacts by asteroids and other small bodies.

"The geologists were excited," he said.

Duke also filmed Young doing a "lunar grand prix" on the rover, driving it back and forth at high speed on video so engineers on Earth could see how the rover performed in lunar gravity, which is only one-sixth that of Earth's gravity.

After the flight

Duke left NASA in 1975 with Apollo 16 as his only spaceflight. He still spends much of his time promoting the flight to groups all over the world; his Delta Air Lines miles add up to the equivalent of seven round-trip lunar flights, he said. But Duke also enjoys flounder fishing, investing in technology companies and spending time with his wife, children and nine grandchildren.

He also continues to follow new developments arising from Apollo 16. For example, NASA's Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has imaged both the landing site and the impact site from the mission's Saturn IV-B rocket stage. The rocket stage impact site was unknown for 43 years, until the LRO spotted it.

"It's really unique to look back at those [LRO] photographs and see the old landing site of Apollo 16," Duke said.

He added that he sees a resurgence of interest in spaceflight these days due to the proliferation of science-fiction films focusing on space. For NASA's ongoing astronaut selection, he added, more than 18,000 people applied for only a handful of spots. The new astronaut class – NASA's 22nd group – will also be announced today.

"When I graduated from college, there was no astronaut program," Duke recalled. He was in high school when Sputnik, humanity's first artificial satellite, launched in 1957. The first U.S. astronaut launched in 1961..

But Duke said he had an engaging career in the Air Force before becoming an astronaut, and urged any astronaut hopefuls to first consider their interests before trying for the program.

"Pick a career you really like," Duke said, "and even if you never get selected for an astronaut, you will have … a lifelong career that will be stimulating and exciting."

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.