Life on Earth may not have been possible without comet strikes.

A new study suggests that about 20 percent of the noble gas xenon in Earth's atmosphere was delivered by comets long ago. And these icy wanderers likely brought lots of other stuff to our planet as well, researchers said.

The "cometary contribution could have been significant for organic matter, especially prebiotic material, and could have contributed to shape the cradle of life on Earth," said study lead author Bernard Marty, a geochemist at the University of Lorraine and the Centre de Recherches Pétrographiques et Géochimiques in France. [7 Theories on the Origin of Life]

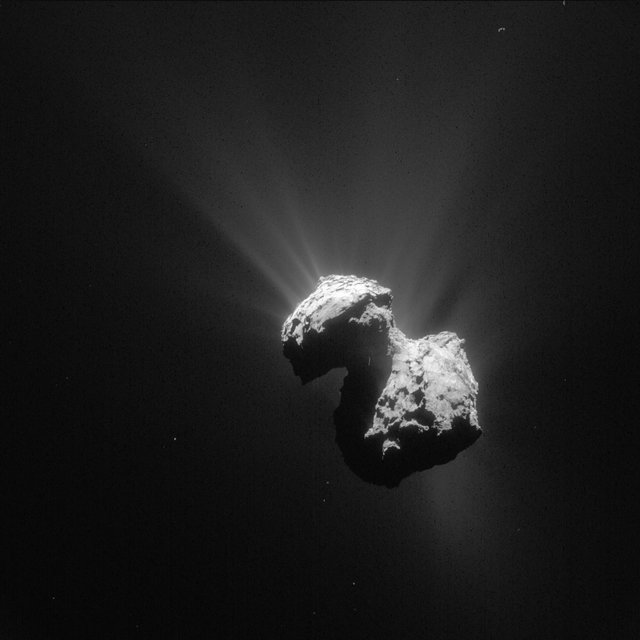

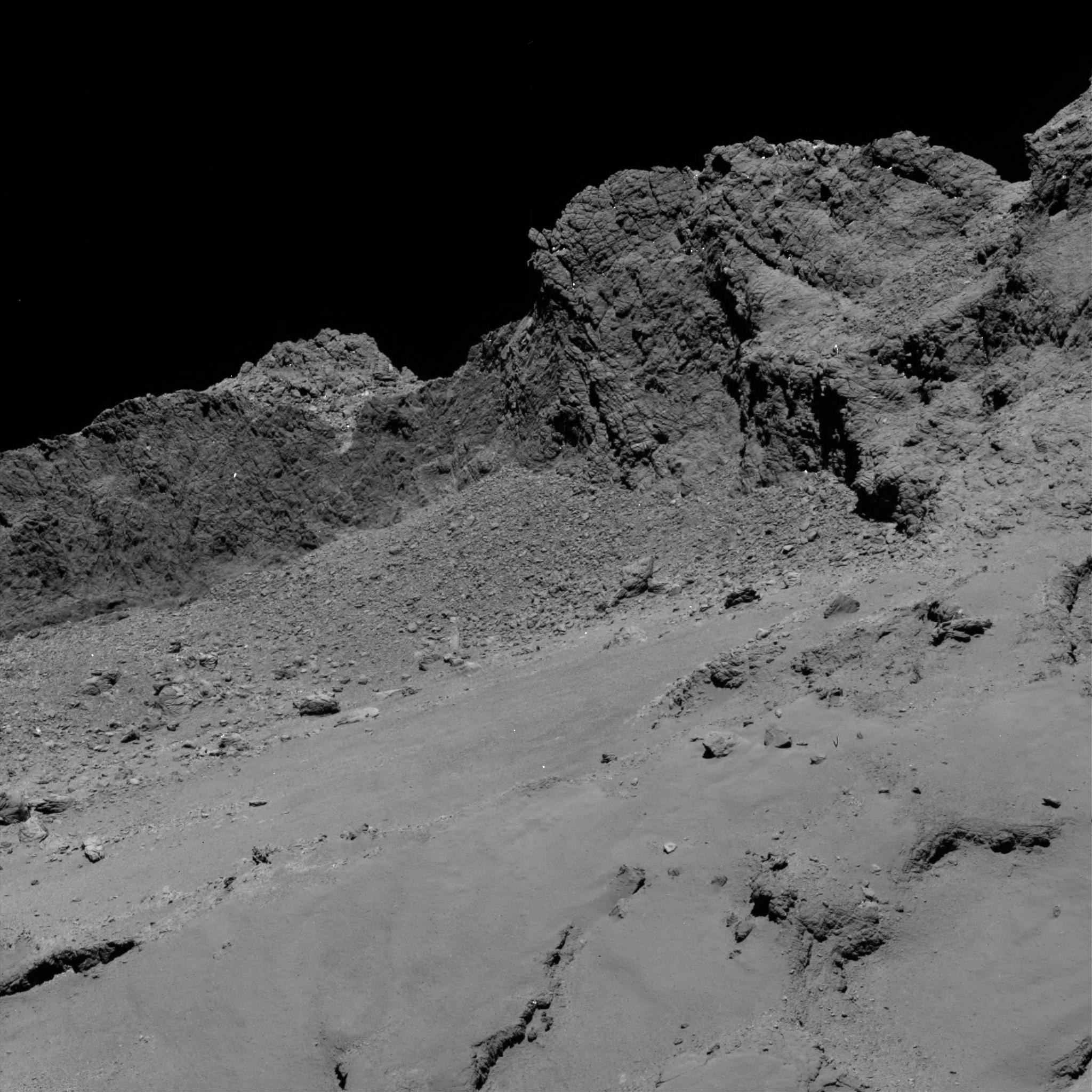

Marty and his colleagues studied measurements made by the European Space Agency's (ESA) Rosetta spacecraft, which orbited the 2.5-mile-wide (4 kilometers) Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko from August 2014 through September of last year.

Specifically, they analyzed xenon-isotope data that Rosetta gathered during a series of low-altitude orbits of Comet 67P between May 14 and May 31, 2016. (Isotopes are versions of an element that contain different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei. "Heavy" isotopes have more neutrons compared to "lighter" ones.)

Rosetta's observations revealed that 67P is deficient in heavy xenon. Furthermore, the team determined that the comet's xenon isotope composition matches a signature of Earth xenon whose origin had been a mystery.

"These findings establish for the first time a genetic link between comets and the atmosphere of the Earth," Marty told Space.com via email. "This link is not only qualitative but also quantitative, as it permits [us] to decipher for xenon what was the proportion of cometary Xe added to the Earth relative to asteroidal (meteoritic) Xe."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That proportion is 22 percent cometary, plus or minus 5 percent, with asteroids providing the remainder, the researchers report in the new study, which was published online today (June 8) in the journal Science.

Scientists think asteroids delivered the vast majority of the water in Earth's oceans, and these space rocks have been regarded as the chief suppliers of the planet's other "volatiles" — substances with low boiling points, such as nitrogen, carbon dioxide and noble gases — as well. (Models suggest that Earth was extremely hot shortly after its formation about 4.5 billion years ago, so it probably lost its primordial volatiles early on.)

This inference is drawn partly from the isotopic similarity of hydrogen, nitrogen and other materials on Earth to that of certain asteroids known as carbonaceous chondrites, as measured in meteorite samples, Marty said.

"There was also a dynamical argument: Jupiter and the other giant planets formed early, and the outer solar system (from which comets originate) was isolated early from the inner solar system by the giant planets' gravitational fields," he said. "Now our finding calls for a revision of such models."

Comets are especially enriched in noble gases, explaining how their contribution of xenon (and perhaps other materials) to the early Earth can be outsized compared to the proportion of water these icy wanderers delivered, Marty added.

The newly analyzed Rosetta data also indicate that 67P's xenon predates the solar system — that is, the comet contains samples of interstellar matter. That's an exciting result that argues for further, more detailed study of pristine cometary material, Marty said.

"Returning a cometary sample on Earth should be the highest priority, because it will permit analyses with unprecedented precision of such exotic material and could respond to questions such as: How long interstellar material can survive, which stars contributed to shape the cradle of the solar system, what is the origin(s) of the large isotopic variations of some of the elements (e.g., N, H, O), what was the role of irradiation of early solar system material, etc.," he said. (N, H and O are nitrogen, hydrogen and oxygen, respectively.)

Rosetta launched in March 2004. A decade later, it became the first mission ever to orbit a comet and the first to touch down softly on one of these bodies. (The Rosetta orbiter dropped a lander called Philae onto 67P in November 2014.)

The mission ended when Rosetta intentionally crash-landed on 67P's surface on Sept. 30, 2016.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.