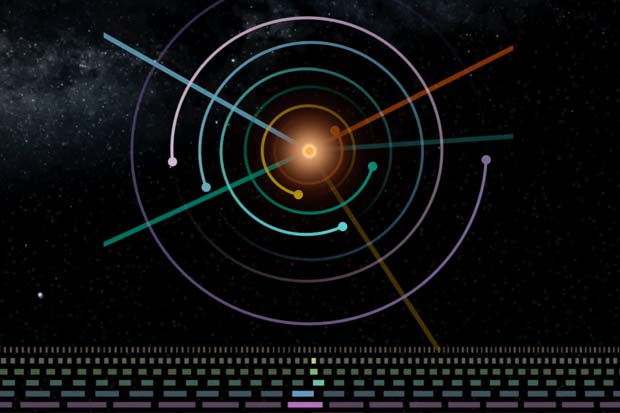

The seven Earth-size planets in the TRAPPIST-1 system zip around their host star in perfect harmony, as a dazzling new animation shows.

A team of researchers and musicians has transformed the orbits of the seven TRAPPIST-1 worlds into music. A piano note represents each "transit" of a planet across the host star's face, and a drum beat plays each time one of the worlds overtakes its nearest neighbor.

The result is a surprisingly rich and melodious celestial symphony. [Meet the 7 Earth-Size Planets of TRAPPIST-1]

"Most planetary systems are like bands of amateur musicians playing their parts at different speeds," team member Matt Russo, a postdoctoral researcher at the Canadian Institute for Theoretical Astrophysics (CITA) in Toronto, said in a statement. "TRAPPIST-1 is different; it’s a super-group with all seven members synchronizing their parts in nearly perfect time."

Indeed, the seven TRAPPIST-1 planets are in "resonance" with each other, meaning they have orbital periods that form ratios of whole numbers. For example, for every two orbits of TRAPPIST-1h (the outermost planet in the system), the other six worlds zip around the parent star three, four, six, nine, 15 and 24 times, respectively.

No other known planetary system harbors so many resonant worlds; second place is a tie between Kepler-80 and Kepler-223, each of which is known to have four resonant planets.

The TRAPPIST-1 planets circle a small, dim star about 39 light-years from Earth. Three of the worlds appear to lie in the "habitable zone" — the range of distances from a star where liquid water, and perhaps life as we know it, could exist on a planet's surface.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The TRAPPIST-1 system is thought to be 3 billion to 8 billion years old, astronomers have said. The seven planets' continued existence had been something of a mystery; computer simulations suggest that the worlds should have started slamming into each other less than 1 million years after their formation.

But resonance apparently saved them. The planets were likely able to settle into their system-stabilizing resonant orbits soon after they formed, according to a recent study in Astrophysical Journal Letters led by Dan Tamayo, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Toronto’s Centre for Planetary Sciences and CITA.

Tamayo worked with Russo and Toronto musician Andrew Santaguida to create the new TRAPPIST-1 symphony.

"It seems somehow poetic that this special configuration that can generate such remarkable music can also be responsible for the system surviving to the present day," Tamayo said in the same statement.

You can read all about the TRAPPIST-1 animation — and how Tamayo, Russo and Santaguida made it — here: http://www.system-sounds.com/trappist-sounds/.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.