The Missing Link: Where Are Medium-Size Black Holes?

For decades, while astronomers have detected black holes equal in mass either to a few suns or millions of suns, the missing-link black holes in between have eluded discovery. Now, a new study suggests such intermediate-mass black holes may not exist in the modern-day universe because of the rate at which black holes grow.

Scientists think stellar-mass black holes — up to a few times the sun's mass — form when giant stars die and collapse in on themselves. Over the years, astronomers have detected a number of stellar-mass black holes in the nearby universe, and in 2010, researchers detected the first such black hole outside the local cluster of nearby galaxies known as the Local Group.

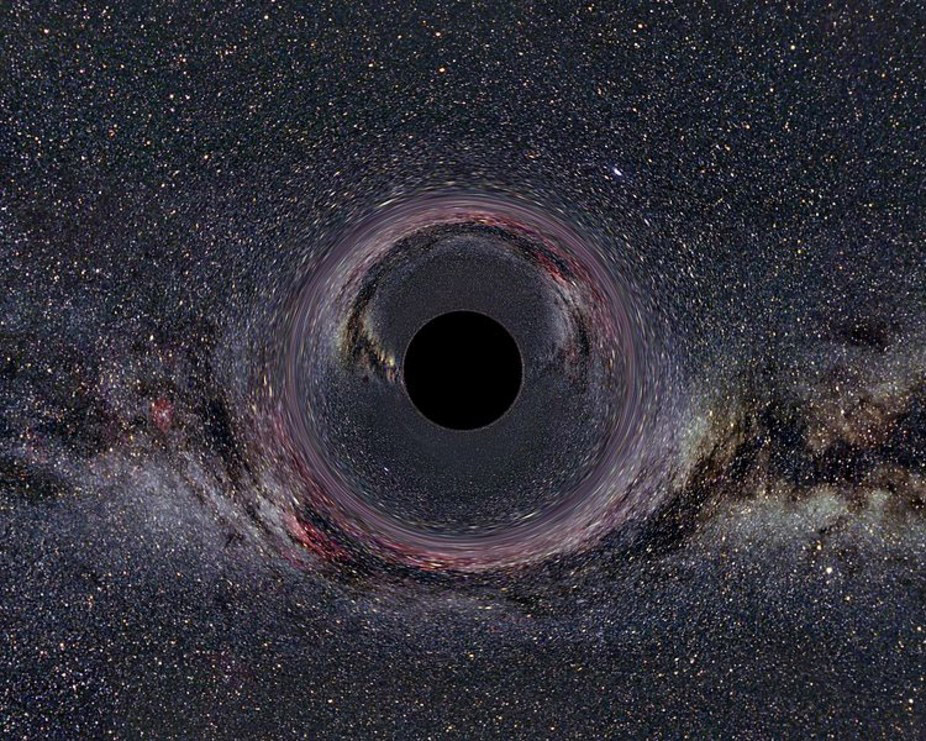

As big as stellar-mass black holes might seem, they are tiny in comparison to the so-called supermassive black holes that are millions to billions of times the sun's mass, which form the hearts of most, if not all, large galaxies. The oldest supermassive black holes found to date include one found in 2015 — with a mass of about 12 billion solar masses — that existed when the universe was only about 875 million years old. This finding and others suggest that many black holes were born in the dawn of time, back when the universe was smaller and matter was more concentrated, making it easier for them to form and grow. [No Escape: Dive into a Black Hole (Infographic)]

Much remains uncertain about how black holes reach supermassive girth and influence the universe around them. As such, astronomers want to analyze intermediate-mass black holes of about 100 to 10,000 solar masses that they expect would serve as the middle stages between stellar-mass and supermassive black holes.

However, while astronomers have discovered a number of potential intermediate-mass black holes, the evidence remains inconclusive, said astrophysicists Tal Alexander at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, and Ben Bar-Or at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey.

Now these researchers suggest the dearth of these missing links may be due to the rate at which black holes may grow. They detailed their findings online June 19 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

In recent years, scientists have discovered a dozen or so instances of black holes devouring stars. If black holes grew solely by consuming stars and dense, compact objects such as white dwarfs and neutrons stars instead of, say, giant clouds of gas or dark matter, the researchers estimated that black holes would still grow at the relatively constant rate of one solar mass per 10,000 years. (If they could eat gas or dark matter, they could grow even faster, but the data regarding such materials in the early universe is more open to question.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Although one solar mass per 10,000 years may not seem especially quick, it means that even a stellar-mass black hole could grow completely past the intermediate-mass stage after 10 billion years. In comparison, the universe is about 13.8 billion years old.

These findings suggest that the seeds for supermassive black holes "were created quite early on in galaxies, when things were more dense," Bar-Or told Space.com. These seeds already exceeded intermediate-mass stage by about 1.6 billion to 2.2 billion years after the Big Bang — "some or even most of the black holes may have passed the supermassive-black-hole mass threshold even earlier," Alexander told Space.com.

Although the researchers said that intermediate-mass black holes may exist in the present day in dense areas such as globular clusters of stars, they remain difficult to identify because the light produced by objects falling into them is "not spectacular, and there are other objects that can produce it," Alexander said.

Instead, "the ultimate way of finding and identifying intermediate-mass black holes is not by the emission of light, but by the emission of gravitational waves," Alexander said. Gravitational waves are ripples in the fabric space and time, and the Evolved Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (ELISA) mission currently planned for 2034 could detect gravitational waves generated "when two intermediate-mass black holes coalesce together, Alexander said.

Follow Charles Q. Choi on Twitter @cqchoi. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us