Clearest-Ever Image of Betelgeuse Reveals Mysteries of the Red Giant (Video)

The red giant star Betelgeuse is younger than the sun, but it's living fast: The star has reached a life stage that the sun won't hit for billions of years. New photos of the young star may help reveal the upheaval behind its mature appearance.

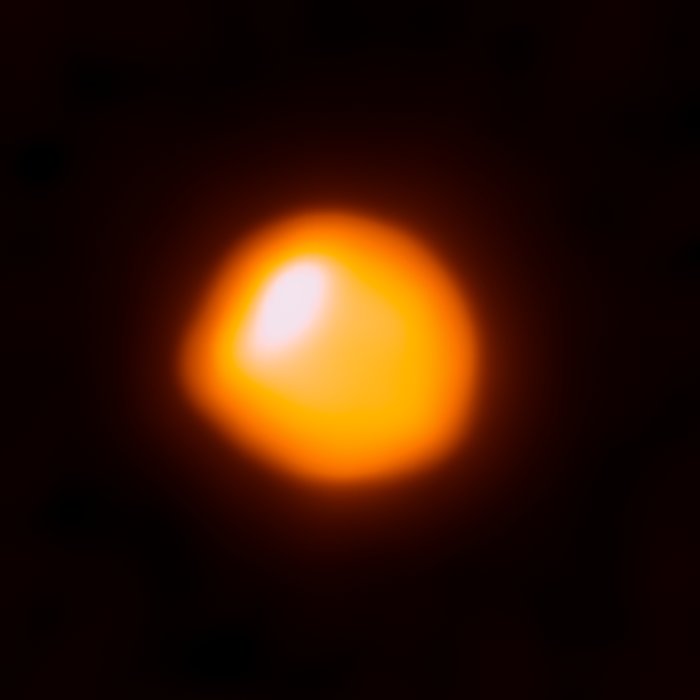

Stretched along the Chajnantor plateau in the Chilean Andes, the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array Telescope, known as ALMA, captured its first image of the surface of this star. In doing so, it has provided astronomers and enthusiasts alike with the highest-resolution image ever captured of the red supergiant, European Southern Observatory (ESO) officials said in a statement.

If you are a keen night-sky observer, an introduction to basic astronomy has likely included a look at the constellation Orion, which appears high in the Northern Hemisphere's skies during the winter months. Sitting on the hunter's right shoulder is a star that shines red, unlike the rest of the stars that the naked eye can make out. [Meet ALMA: Amazing Photos from Giant Radio Telescope]

Besides its intriguing ruby-red hue, Betelgeuse also fascinates astronomers because it shines so brightly at such a young age. It is an astronomical example of the phrase, "I may have been born yesterday, but I stayed up all night." It is only 8 million years old, making the sun well over 500 times older, but Betelgeuse boasts a radius 1,400 times larger than the sun's, ESO officials said in the statement. If Betelgeuse sat inside of Earth's solar system, the star would swallow the planets all the way up to Jupiter's orbit.

Betelgeuse is located just 600 light-years from Earth, and it will shortly, astronomically speaking, create a stunning supernova that will be visible on Earth, even in broad daylight. Previous work using ESO's Very Large Telescope (VLT) has shown that the star sported a vast plume of gas and that it has an enormous bubble boiling on its surface, often becoming close to the size of the star itself, according to a statement.

The sensitivity of ALMA's detection system allows for increasingly nuanced and precise findings. That's because, unlike many telescopes that observe visible light, the collection of antennas that make up ALMA detect radio wavelengths, which can penetrate the gas and dust that obscures other views.

ALMA consists of 66 antennas, and the telescope dishes have diameters ranging from 7 to 12 meters (23 to 39 feet). The reflective surface of each dish captures radiation from a distant celestial object and focuses it into a detector that then measures the light. When the wave is converted into a digital signal, it is carried over 10 miles (16 kilometers) to an operations-support facility, which then combines the outputs of the many antennas into a single image.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The M in ALMA stands for millimeter, which is the wavelength size of the radiation that the telescope dishes capture. On the electromagnetic spectrum, these waves sit between infrared and radio waves. The surfaces of the dishes are so accurate, they can measure to within 25 micrometers.

VLT captured features that helped explain the tremendous rates at which Betelgeuse sheds gas and dust, and now ALMA has been able to detect the localized temperature increases that make the star's surface uneven. The submillimeter wavelengths that ALMA can detect are coming from the red supergiant star's lower chromosphere, giving a glimpse of life below the surface of the star.

Editor's Note: Video produced and edited by Space.com's Steve Spaleta.

Follow Doris Elin Salazar on Twitter @salazar_elin. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Doris is a science journalist and Space.com contributor. She received a B.A. in Sociology and Communications at Fordham University in New York City. Her first work was published in collaboration with London Mining Network, where her love of science writing was born. Her passion for astronomy started as a kid when she helped her sister build a model solar system in the Bronx. She got her first shot at astronomy writing as a Space.com editorial intern and continues to write about all things cosmic for the website. Doris has also written about microscopic plant life for Scientific American’s website and about whale calls for their print magazine. She has also written about ancient humans for Inverse, with stories ranging from how to recreate Pompeii’s cuisine to how to map the Polynesian expansion through genomics. She currently shares her home with two rabbits. Follow her on twitter at @salazar_elin.