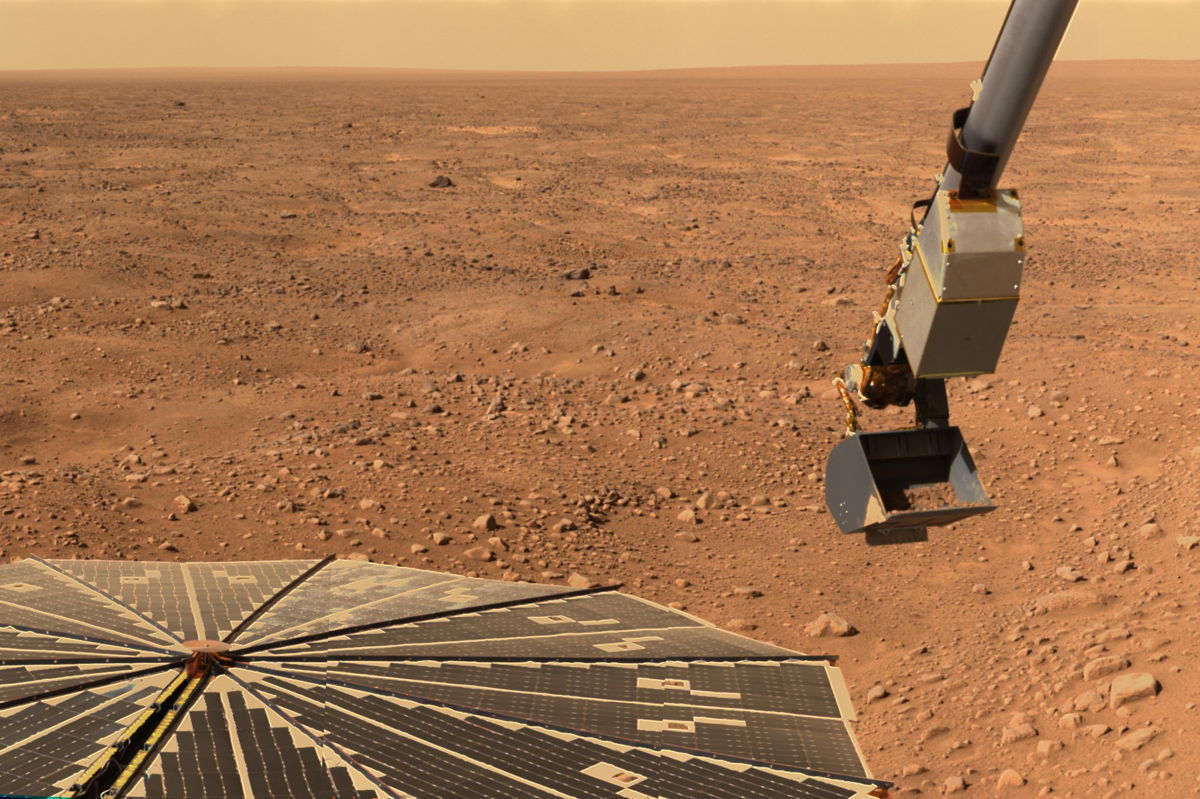

The Martian surface may be even less hospitable to life than scientists had thought.

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation streaming from the sun "activates" chlorine compounds in the Red Planet's soil, turning them into potent microbe-killers, a new study suggests.

These compounds, known as perchlorates, seem to be widespread in the Martian dirt; several NASA missions have detected them at a variety of locations. Perchlorates have some characteristics that would appear to boost the Red Planet's habitability. They drastically lower the freezing point of water, for example, and they offer a potential energy source for microorganisms, scientists have said. [The Search for Life on Mars: A Photo Timeline]

But the new study, by Jennifer Wadsworth and Charles Cockell — both of the U.K. Centre for Astrobiology at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland — paints perchlorates in a different light. The researchers exposed the bacterium Bacillus subtilis, a common spacecraft contaminant, to perchlorates and UV radiation at levels similar to those found at and near the Martian surface. (Because Mars' atmosphere is just 1 percent as thick as that of Earth, UV fluxes are much higher on the Red Planet than on Earth.)

The bacterial cells lost viability within minutes in Mars-like conditions, the researchers found. And the results were even more dramatic when Wadsworth and Cockell added iron oxides and hydrogen peroxide, two other common components of Martian regolith, to the mix: Over the course of 60 seconds, the combination of irradiated perchlorates, iron oxides and hydrogen peroxide boosted the B. subtilis death rate by a factor of 10.8 compared to cells exposed to UV radiation alone, the researchers found.

"These data show that the combined effects of at least three components of the Martian surface, activated by surface photochemistry, render the present-day surface more uninhabitable than previously thought and demonstrate the low probability of survival of biological contaminants released from robotic and human exploration missions," Wadsworth and Cockell wrote in the study, which was published online today (July 6) in the journal Scientific Reports. (Scientists already knew about perchlorates' toxic potential, but it usually takes high temperatures to "activate" the compounds, Wadsworth told Space.com.)

It's unclear how deep this inferred "uninhabitable zone" goes on Mars, because the precise mechanism behind the cell-killing action isn't understood, Wadsworth said.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"If you're looking for life, you have to additionally keep the ionizing radiation in mind that can penetrate the top layers of soil, so I'd suggest digging at least a few meters into the ground to ensure the levels of radiation would be relatively low," she told Space.com via email.

The European/Russian ExoMars rover, which is scheduled to launch toward the Red Planet in 2020 on a mission to search for signs for life, will feature a drill that can reach a maximum depth of 6.5 feet (2 m).

There's an important caveat to the new results, however: B. subtilis is a garden-variety microbe, not an "extremophile" adapted to survive in harsh conditions, the researchers said.

"It's not out of the question that hardier life forms would find a way to survive" at or near the Martian surface, Wadsworth told Space.com. "It's important we still take all the precautions we can to not contaminate Mars."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.