New Moon-Rock Recipe Could Help Test Rovers

A technology for producing a material that closely resembles the rocky regolith found on the surface of the moon could help scientists design better, more resilient lunar rovers.

"The material on the moon is so aggressive that it destroys the technologies that we send up there," Vince Roux, one of the creators of the artificial lunar regolith, told Space.com. "That's why most of the missions have only lasted a few weeks, because the particles get into the joints and seize them up and tear apart the fabric."

So far, researchers have been making lunar-regolith-like material by simply crunching up basalts and similar volcanic rocks that can be found on Earth, crushing them to the correct particle shape and size distribution, according to Roux. [Moon Facts: Fun Information About the Earth's Moon]

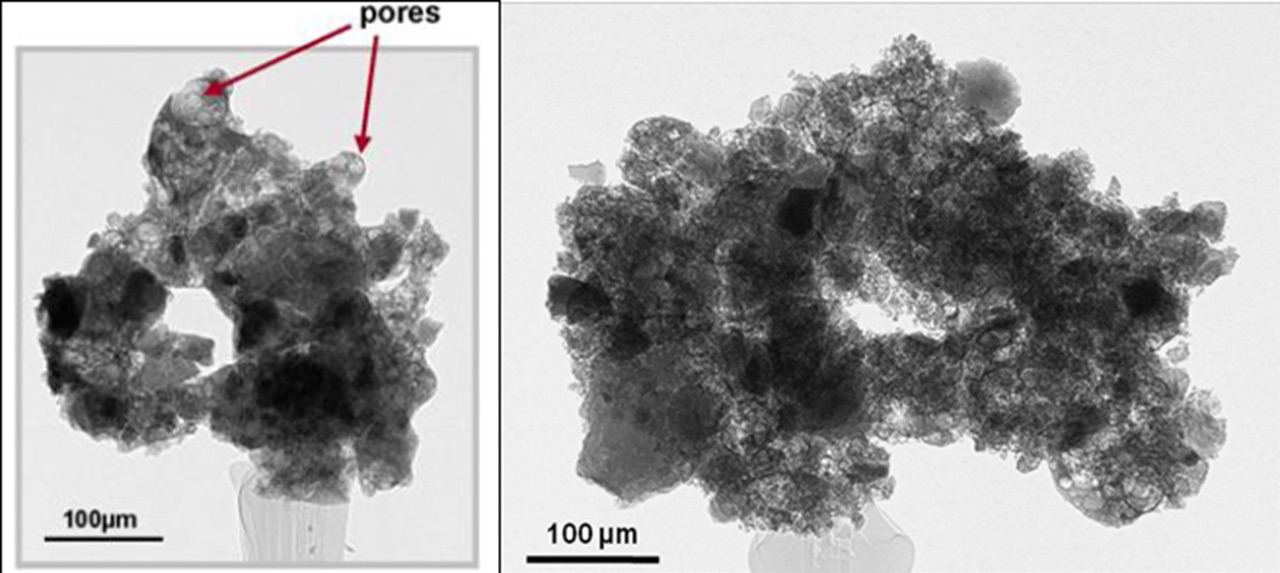

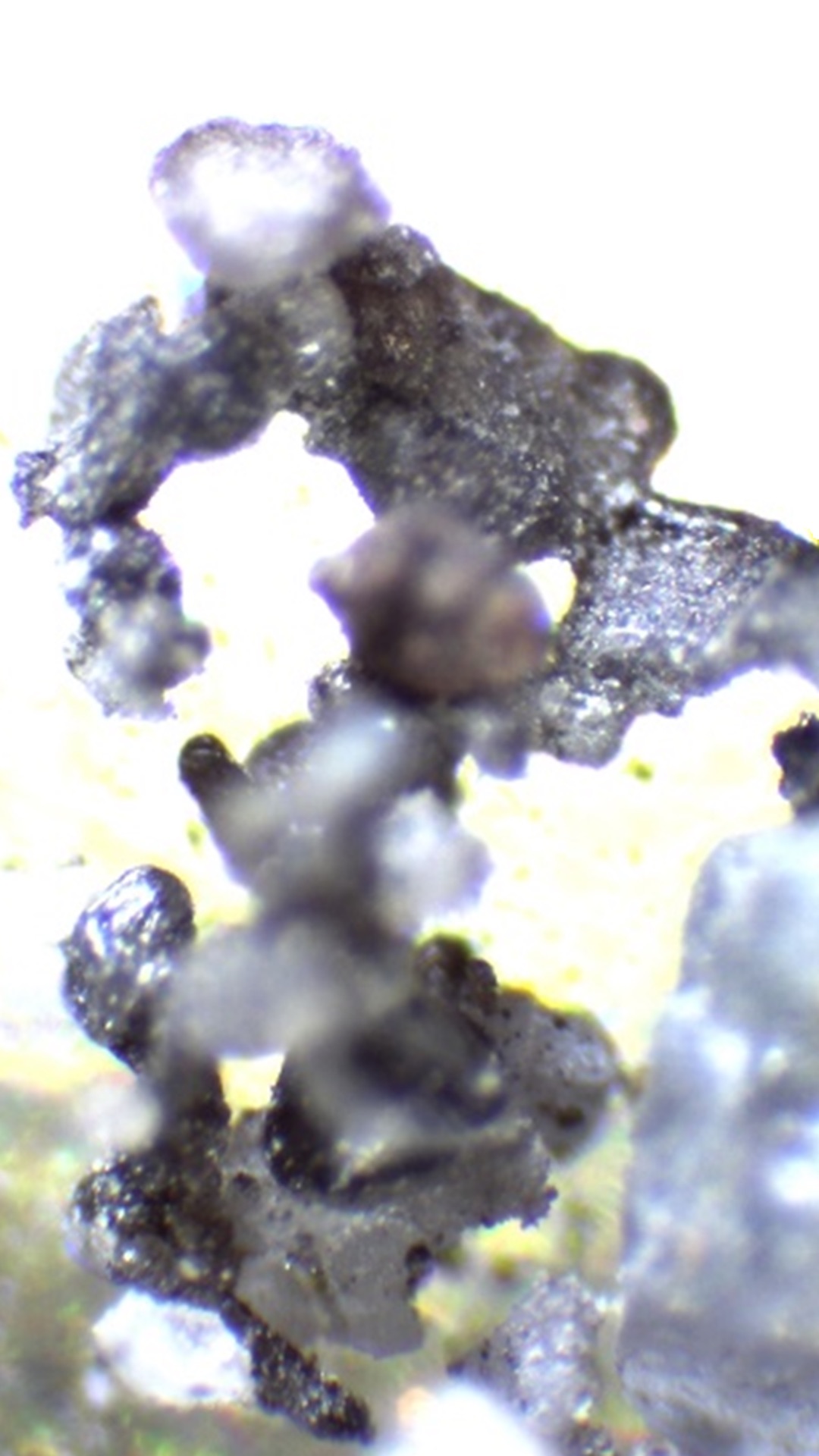

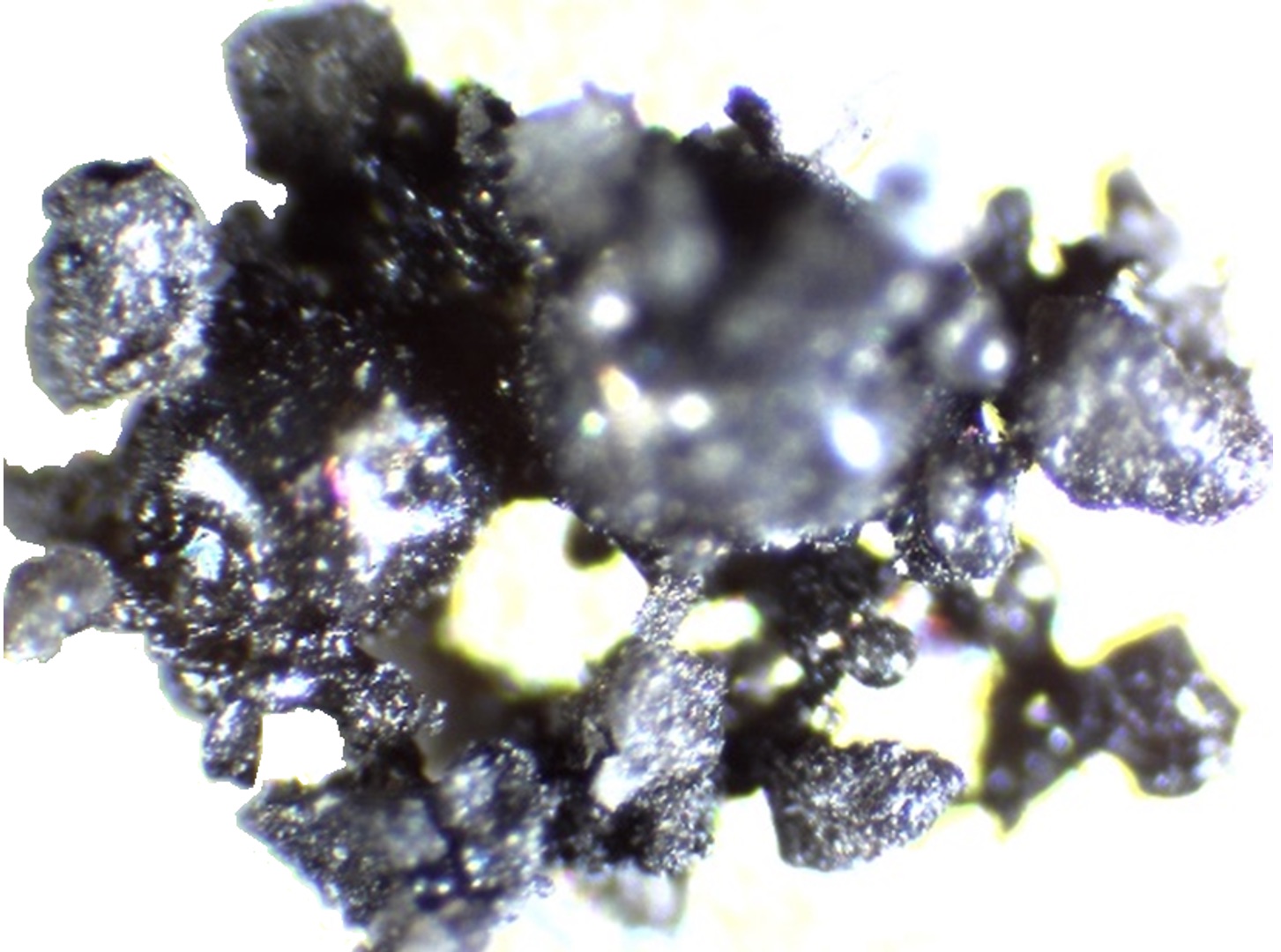

Roux and his collaborators decided instead to build a machine that would simulate the natural geological processes that take place on the moon. The team focused on the formation of agglutinates: particles of melted lunar soil that form during micrometeorite impacts.

"[The] moon doesn't have an atmosphere, so these small particles reach the surface easily," Melissa Roth, who is collaborating with Roux on the project, told Space.com. "When these small particles hit the soil, it heats up and some of the lunar soil particles melt."

It is estimated that millions of micrometeorites less than 1 millimeter (0.04 inches) in diameter strike the moon's surface every day. The agglutinates — a blend of melted glass and mineral fragments — are usually between several tens of micrometers and a few millimeters in size. In some regions, agglutinates make up to 90 percent of the lunar regolith, according to Roux.

"What we decided was to study an individual micrometeorite impact and fully characterize what happens when that little, tiny grain impacts the surface of the moon," said Roux.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Once we were able to understand all the processes that took place during that impact and after that, then we were able to replicate the single tiny event thousands of times per minute to produce [a] higher volume of these microstructures," he said.

There are various types of lunar regolith that vary in composition. The darker type of lunar regolith can be simulated on Earth using volcanic rock basalt, which is rather prevalent on the planet, the engineers said. The older, lighter, type of regolith that can be found in the lunar highlands can be simulated only using a very rare rock called anorthosite.

"Anorthosite was one of the first materials that solidified out of the molten mass that formed the Earth and the moon," said Roux. "As the moon cooled, that material stayed on the surface of the moon. On Earth, that material is reprocessed over billions of years by tectonic activity, and so it's extremely rare now.

"It's really difficult to get to this material, because it's way up in Canada above the Arctic Circle and you can only get to this small batch of material for a couple of months of the year," he said.

The Saint Martin's team managed to obtain 20 tons (18 metric tons) of anorthosite that they plan to use to create a large amount of lunar regolith simulant. They'll first grind the material down to the correct particle size, and then use their machine to mimic micro-meteorite impacts and create agglutinates. The resulting regolith could be used by other researchers and companies to test their technologies before sending them to the moon.

Roux and Roth began the project while they were both undergraduate students at Saint Martin's University in Washington state, where Roux is working on a masters degree. The pair have set up a company called Off Planet Research that will run a testing facility at the Saint Martin's campus. The facility consists of an area about half the size of a tennis court covered in the manufactured regolith at various depths, Roth said.

"It will enable the rovers and other lunar technology to traverse uneven topography and even dig and mess around with the stuff, because we want the technology to break down," she said. "We want it to fail, and then they will refine it and bring it back and then refine it again until all of the sudden it doesn't fail anymore."

The facility will also allow testing of technologies that would utilize the resources in the regolith, such as 3D printers or water-extraction technologies, Roux said.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.