The liquid-hydrocarbon lakes and seas on Titan are incredibly calm, suggesting that future missions to the huge Saturn moon could enjoy a smooth ride to the surface, a new study reports.

The waves rippling the three largest lakes in Titan's northern hemisphere are tiny, according to the study — just 0.25 inches (1 centimeter) high by about 8 inches (20 cm) long.

"There's a lot of interest in one day sending probes to the lakes, and when that's done, you want to have a safe landing, and you don't want a lot of wind," study lead author Cyril Grima, a research associate at the University of Texas Institute for Geophysics (UTIG), said in a statement. "Our study shows that because the waves aren't very high, the winds are likely low." [Amazing Photos: Titan, Saturn's Largest Moon]

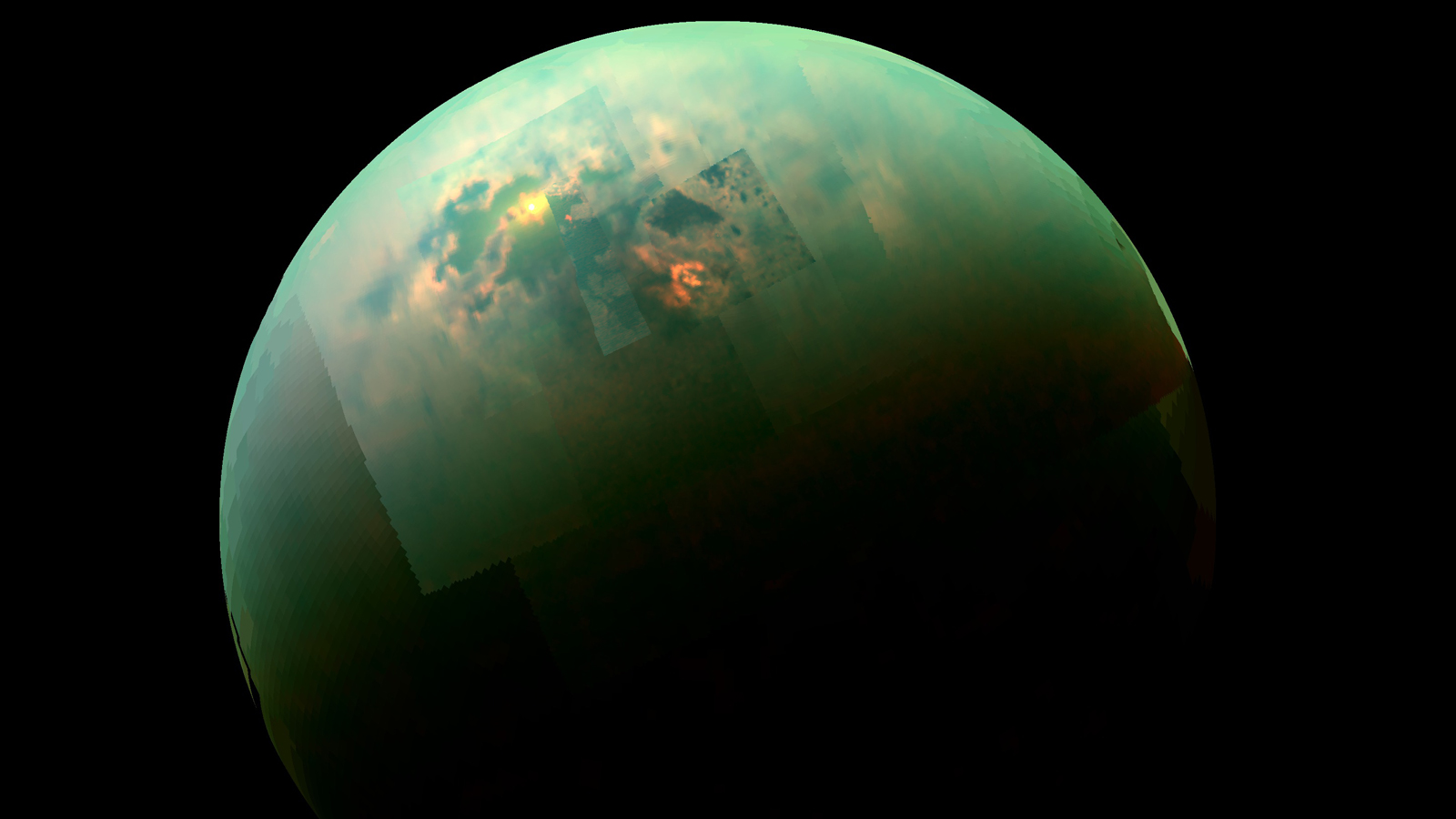

The 3,200-mile-wide (5,150 kilometers) Titan is the only celestial object besides Earth known to host stable bodies of liquid on its surface. But this liquid isn't water. Titan's weather system is hydrocarbon-based; ethane and methane rain from the skies, flowing in rivers and collecting in large lakes and seas.

Some scientists think these lakes and seas may be capable of supporting life, though any organisms swimming on Titan's surface would doubtless be quite different than the water-dependent life-forms of Earth.

"The atmosphere of Titan is very complex, and it does synthesize complex organic molecules — the bricks of life," Grima said. "It may act as a laboratory of sorts, where you can see how basic molecules can be transformed into more complex molecules that could eventually lead to life."

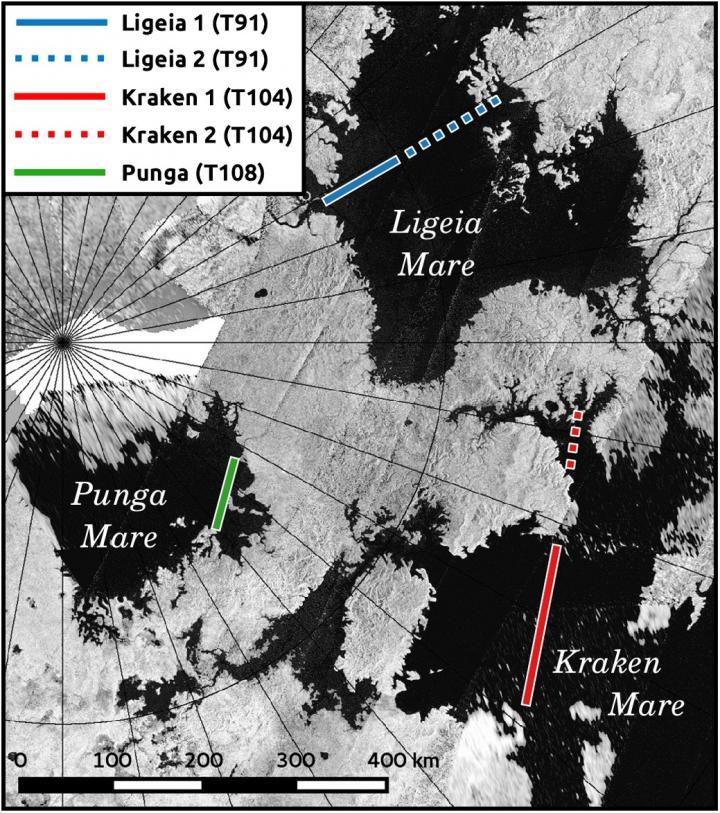

In the new study, Grima and his colleagues analyzed data collected by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, which has been orbiting Saturn since July 2004. Specifically, the team looked at radar measurements of Kraken Mare, Ligeia Mare and Punga Mare that Cassini made in Titan's early summer season. (The largest of these three, Kraken Mare, is about as big as Earth's Caspian Sea.)

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The researchers then calculated wave dimensions, using a technique previously developed by Grima.

"Cyril's work is an independent measure of sea roughness and helps to constrain the size and nature of any wind waves," co-author Alex Hayes, an assistant professor of astronomy at Cornell University in New York state, said in the same statement. "From the results, it looks like we are right near the threshold for wave generation, where patches of the sea are smooth and [other] patches are rough."

Titan's early summer had previously been regarded as the start of a windy season on the moon, researchers said. But the new study, which was published June 29 in the journal Earth and Planetary Science Letters, suggested that this may not be the case.

Titan's surface has been visited once: back in January 2005 by the Huygens lander, which deployed from Cassini. There are currently no firm plans to land another probe on the big moon, but various research groups are working on ideas, including boats andsubmarines that could explore Titan's seas.

Cassini is wrapping up its long and accomplished mission. The orbiter is scheduled to plunge into Saturn's atmosphere on Sept. 15, in an intentional death dive designed to prevent the spacecraft from contaminating Titan or fellow Saturn moon Enceladus with microbes from Earth.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.