8-Legged Extremophile Freaks Will Outlive Humanity (& Maybe the Sun)

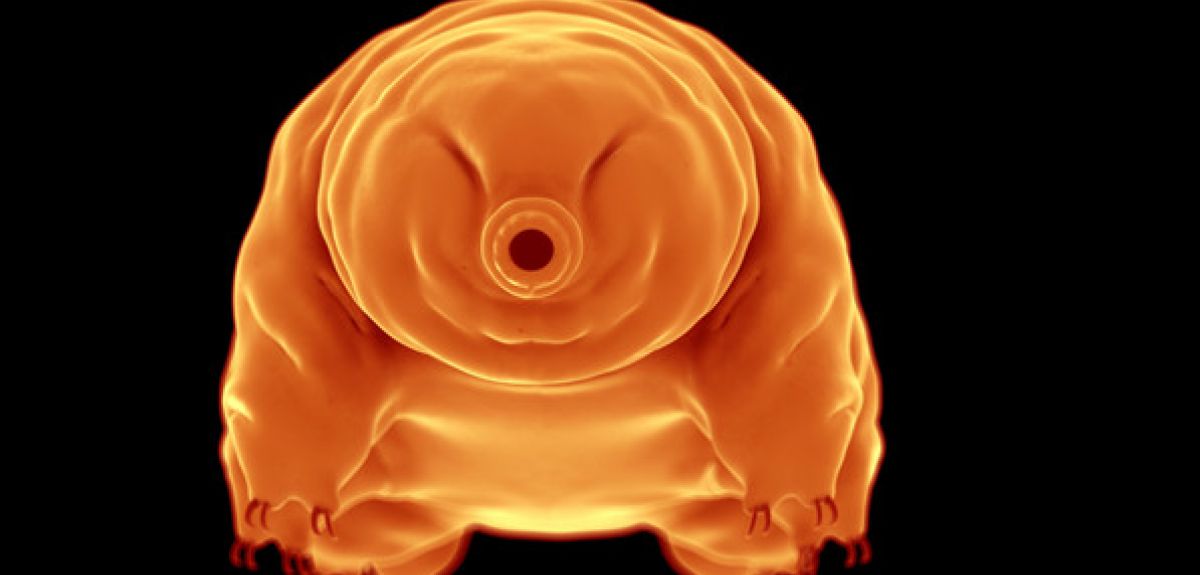

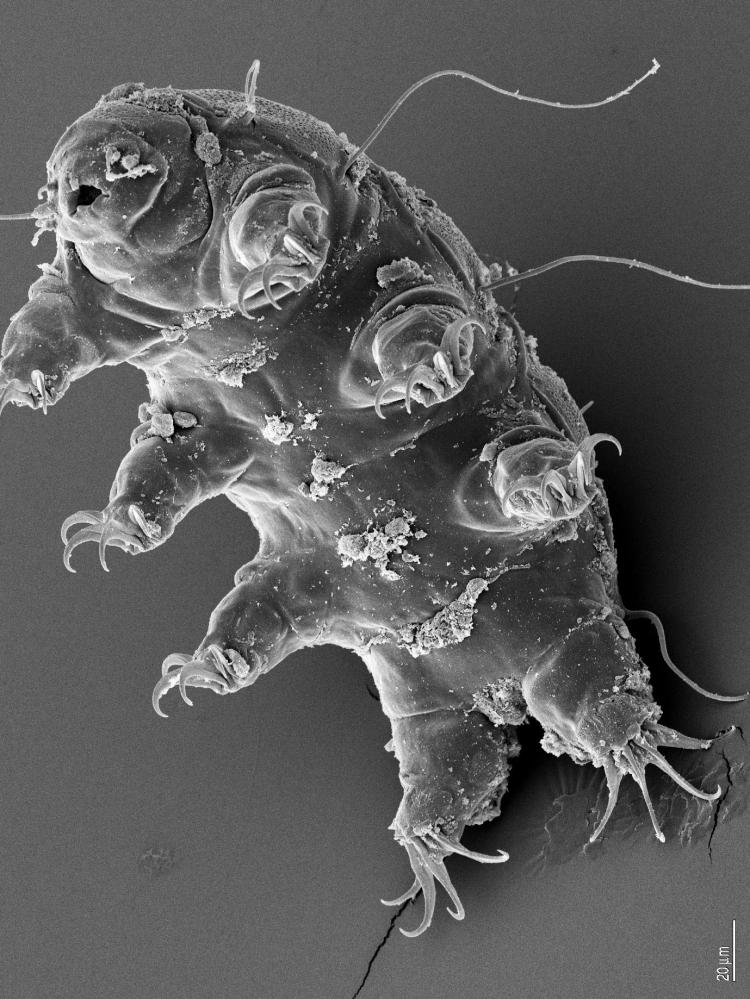

The eight-legged micro-animal called a tardigrade could survive nearly all the way until the death of the sun, a new study suggests — long after humans are history.

The study, from Harvard and Oxford universities, detailed the threats to life on Earth over billions of years, finding that Earth-pummeling asteroids, nearby supernova blasts and gamma-ray bursts would be unlikely to completely sterilize Earth (taking out the little tardigrades in the process).

Tardigrades, which are usually less than a millimeter long (0.04 inches), are nearly indestructible, some of the most resilient forms of life on Earth. They can survive for up to 30 years without eating, and can be frozen, boiled, squished under intense pressure, and exposed to the vacuum and radiation of space without ill effect. The animal, which lives in water (and is also known as a "water bear") can survive for up to 60 years, according to a statement from the University of Oxford. [Earth's 'Alien' Creatures May Reveal Clues About Extraterrestrial Life]

"'A lot of previous work has focused on 'doomsday' scenarios on Earth — astrophysical events like supernovas that could wipe out the human race," David Sloan, a co-author on the new work and researcher at Oxford, said in the statement. "Our study instead considered the hardiest species — the tardigrade. As we are now entering a stage of astronomy where we have seen exoplanets and are hoping to soon perform spectroscopy [on those planets], looking for signatures of life, we should try to see just how fragile this hardiest life is."

"To our surprise, we found that although nearby supernovas or large asteroid impacts would be catastrophic for people, tardigrades could be unaffected," he added. "Therefore, it seems that life, once it gets going, is hard to wipe out entirely. Huge numbers of species, or even entire genera may become extinct, but life as a whole will go on."

The researchers detailed what would happen with each of those threats in a new paper, released today (July 14) in the journal Scientific Reports.

How might Earth die?

Gamma-ray bursts, the most powerful explosions in the universe, are jets of radiation likely released when a star collapses into a black hole after emitting an ultra-powerful supernova blast. If one of those blasts occurred close enough to Earth, heading straight toward the planet, it could take out Earth's ozone layer, leaving Earthlings exposed to deadly radiation levels, the researchers wrote in the paper. But life that lived below ground or in large bodies of water would be shielded from harm and could survive, including the tardigrade.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

To boil away Earth's oceans, the researchers wrote, a gamma-ray burst would have to occur less than 40 light-years away, if it were aimed right toward Earth.

An ordinary, less-powerful supernova would pose the same radiation danger, but it would have to be just 0.14 light-years from Earth to vaporize the oceans and sterilize the planet. One light-year, the distance that light travels in a year, is about 6 trillion miles (10 trillion kilometers).

A killer asteroid could cloud the sky with debris, killing life that relies on sunlight, or even lead to the loss of Earth's atmosphere. But life could live on deep in the ocean, or gather sustenance from volcanic vents, the researchers said. Less than 20 known asteroids and dwarf planets, including Vesta and Pluto, would provide enough of a kick to boil off Earth's oceans with their impacts — and none are headed toward Earth anytime soon.

Calculating the probability of each of those events, and factoring in the heightened temperatures and pressures in which tardigrades can survive, the researchers found an incredibly tiny probability that an ocean-boiling, life-ending event would occur within 10 billion years.

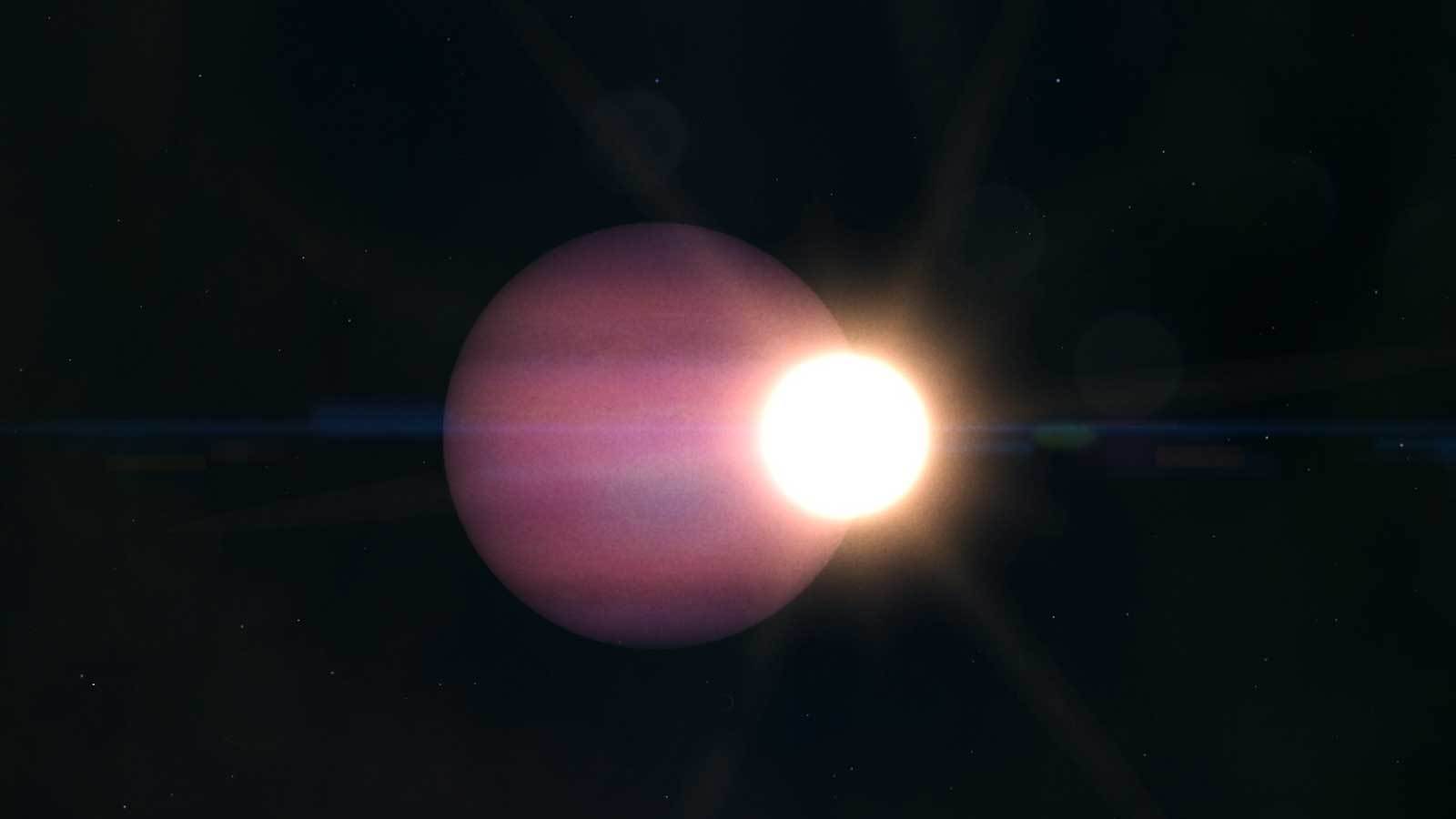

The sun will someday evolve into a red giant star and expand to be even larger in diameter than Earth's orbit. But before that point, the star would get hot and close enough to sterilize Earth for good, boiling away the world's oceans before consuming the planet or knocking it out of orbit — ending the tardigrades' reign at last. [Death of the Sun: How It Will Destroy Earth (Infographic)]

(And even then, the researchers said in the paper, there's a possibility that a planet's orbit will be disturbed enough by its star's expansion that it'll be knocked away early, wandering the galaxy as a rogue world. Scientists have discussed the possibility that creatures like tardigrades could survive on a free-floating planet for a time.)

Looking outward

Studies suggest that Mars once had better conditions for life, including a thicker atmosphere and lakes and streams. If life that developed on planets like Mars is anything like tardigrades, it would stick around despite the planet's current inhospitable conditions, the researchers said.

"It is difficult to eliminate all forms of life from a habitable planet," Avi Loeb, a study co-author and Harvard's chair of astronomy, said in the statement. "The history of Mars indicates that it once had an atmosphere that could have supported life, albeit under extreme conditions. Organisms with similar tolerances to radiation and temperature as tardigrades could survive long term below the surface in these conditions."

Similarly, the subsurface oceans on Saturn's moon Enceladus and Jupiter's moon Europa may feature volcanic vents that provide heat, similar to the locations where tardigrades can thrive deep under Earth's sea, he said.

"Tardigrades are as close to indestructible as it gets on Earth, but it is possible that there are other resilient species examples elsewhere in the universe," added Rafael Alves Batista, a co-author and researcher at Oxford. "If tardigrades are Earth's most resilient species, who knows what else is out there?"

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.