The 2017 Solar Eclipse May Prove the Sun Is Bigger Than We Think

A growing number of researchers think that the sun is actually larger than commonly thought.

Scientists don't know the sun's size as precisely as the details of the Earth and moon, making it a sticking point for perplexed eclipse modelers.

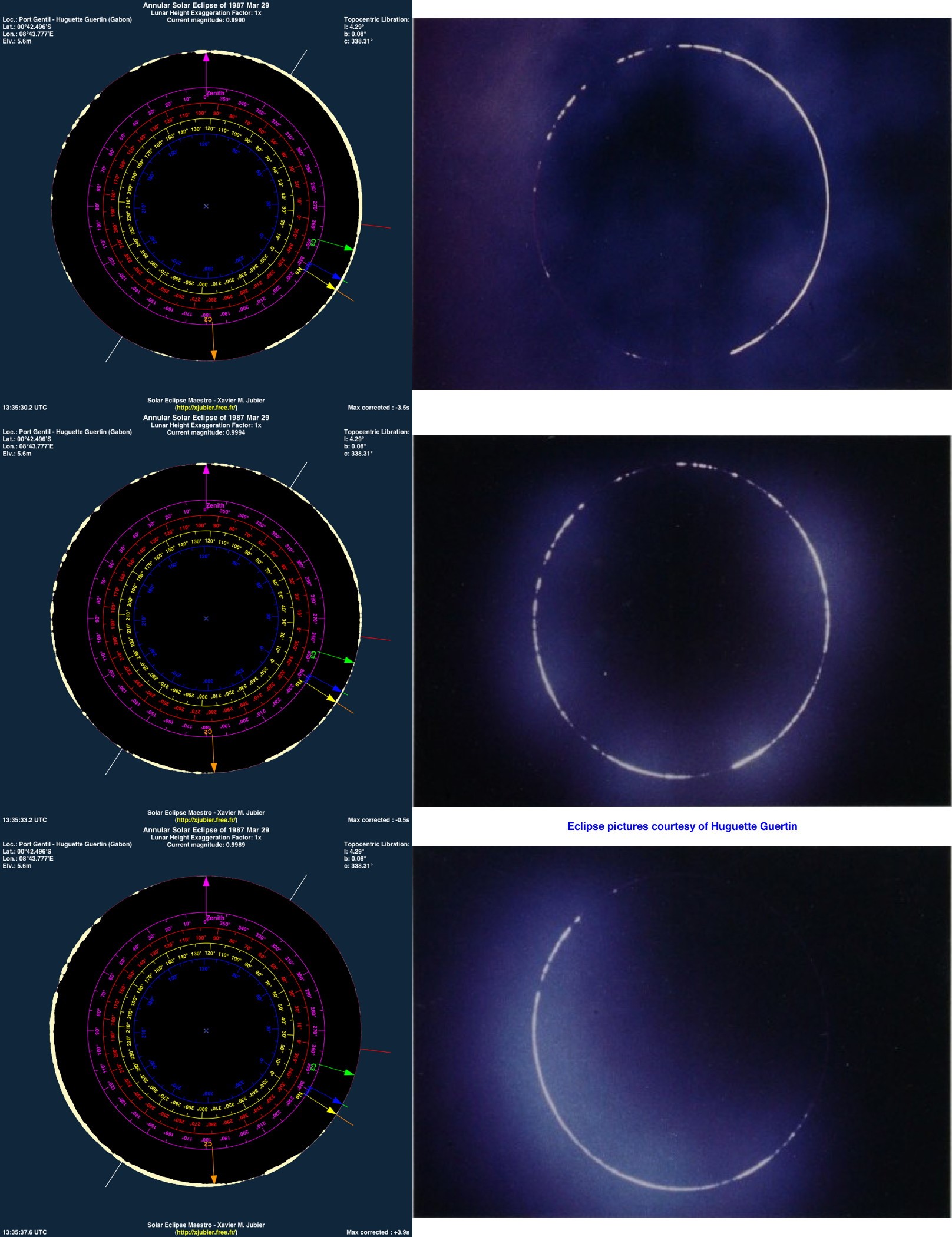

Xavier Jubier creates detailed models of solar and lunar eclipses that work with Google Maps to show precisely where the shadow of the moon will fall on the Earth, and what the eclipse will look like at each point. He came to realize there was something off about the sun's measurements as he matched his eclipse simulations with actual photos. The photos helped him identify exactly where an observer had been for historical eclipses — but those precise eclipse shapes only made sense if he scaled up the sun's radius by a few hundred kilometers. [Total Solar Eclipse 2017: When, Where and How to See It (Safely)]

"For me, something was wrong somewhere, but that's all I could say," Jubier told Space.com.

Scientists' knowledge of the Earth's and moon's contours weren't exact enough to highlight this discrepancy until about 10 years ago — the same time that modern eclipse simulations became possible through computer power and precision mapping. So it was around then that Jubier began to realize something was amiss.

NASA researcher Ernie Wright came to a similar conclusion as he began to create increasingly precise models of solar eclipses, starting about two years ago. He, too, had to scale up the sun slightly from the traditional size for his calculations to match reality.

"How can you not know this?" Wright recalls thinking. "You just hold a ruler up to the sky, and you say it's this big."

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But as it turns out, it's not that simple, Wright told Space.com.

Where did it come from?

Historically, researchers have used the value 696,000 km as the radius of the sun's photosphere — the body of the sun whose wavelengths are visible to the naked eye on Earth. The value was first published in 1891 by the German astronomer Arthur Auwers, Wright said, and it was taken as a standard value for quite some time. In 2015, the International Astronomical Union defined a "unit" based on the sun's radius as a similar 695,700 km, based on a 2008 study, so researchers can use that value to compare the sizes of other stars in the universe.

But efforts to measure the sun's radius have never been accurate enough to match our knowledge of the moon's and the Earth's contours, the researchers said. Scientists have tried measuring it through transits of Mercury and Venus — when those planets cross the face of the sun — and through images taken from sun-observing satellites like the Solar Dynamics Observatory. Each pixel on SDO's higher resolution images covers about 270 miles (435 km), Wright said, which means there's a limit to how precisely the size of the photosphere can be measured with this method. In addition, orbiting solar telescopes like SDO generally collect wavelengths of light emitted deeper inside or further outside the sun, rather than its visible photosphere.

"It's harder than you think just to put a ruler on these images and figure out how big the sun is — [SDO] doesn't have enough precision to nail this down," Wright said. "Similarly, with the Mercury and Venus transits, it turns out [a measurement based on those is] not quite as precise as you'd like it to be."

Different papers trying to pin down the sun's radius, using planet transits, space-based sensors as well as ground observations, have produced results that differ by as many as 930 miles (1,500 km), and can't seem to be reconciled with one another, Wright said. And for eclipse modelers, it's a critical and irritating problem.

Eclipse viewers might find the uncertainty of interest, as well, as they plot out where they'll be in the path of totality. A slightly larger sun means the period of total blackout can be a few seconds shorter in the center of the path, and the path itself would warp, as well.

"For most people, yes, it doesn't really matter; it won't change everything," Jubier said. "But the closer you get to the edge of the [eclipse] path, the more risk you take." If the sun is indeed bigger, the path is narrower than projections made with the usual value would suggest. So those chasing the effects on the eclipse's edge could be in trouble if they're not using a large enough value for their calculations.

Few people do eclipse predictions, Jubier added, and the precise value isn't necessary to a lot of researchers. Because of that, definitions can vary and it's hard to compare different values to one another, including the original 1891 value. It can be hard to tell for a given study what assumptions went into their answer for the sun's diameter, and so they can't be adapted easily to match each other or the eclipse. Any discrepancies in eclipse measurements can be attributed to not fully understanding the values, Jubier added.

"It is definitely still an area of ongoing research, and something that the field itself is interested in getting a better handle on," C. Alex Young, a solar astrophysicist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland, told Space.com. "Probably a little esoteric for many people, and I would say that the calculation is not as important for a lot of areas, for example in solar physics, in terms of the accuracy needed. But especially the eclipse community is very interested in the accuracy."

Figure it out

Michael Kentrianakis, an avid eclipse chaser and a member of the American Astronomical Society's Solar Eclipse Task Force, learned about the confusion over the sun's size from his colleague Luca Quaglia, a physicist and eclipse researcher.

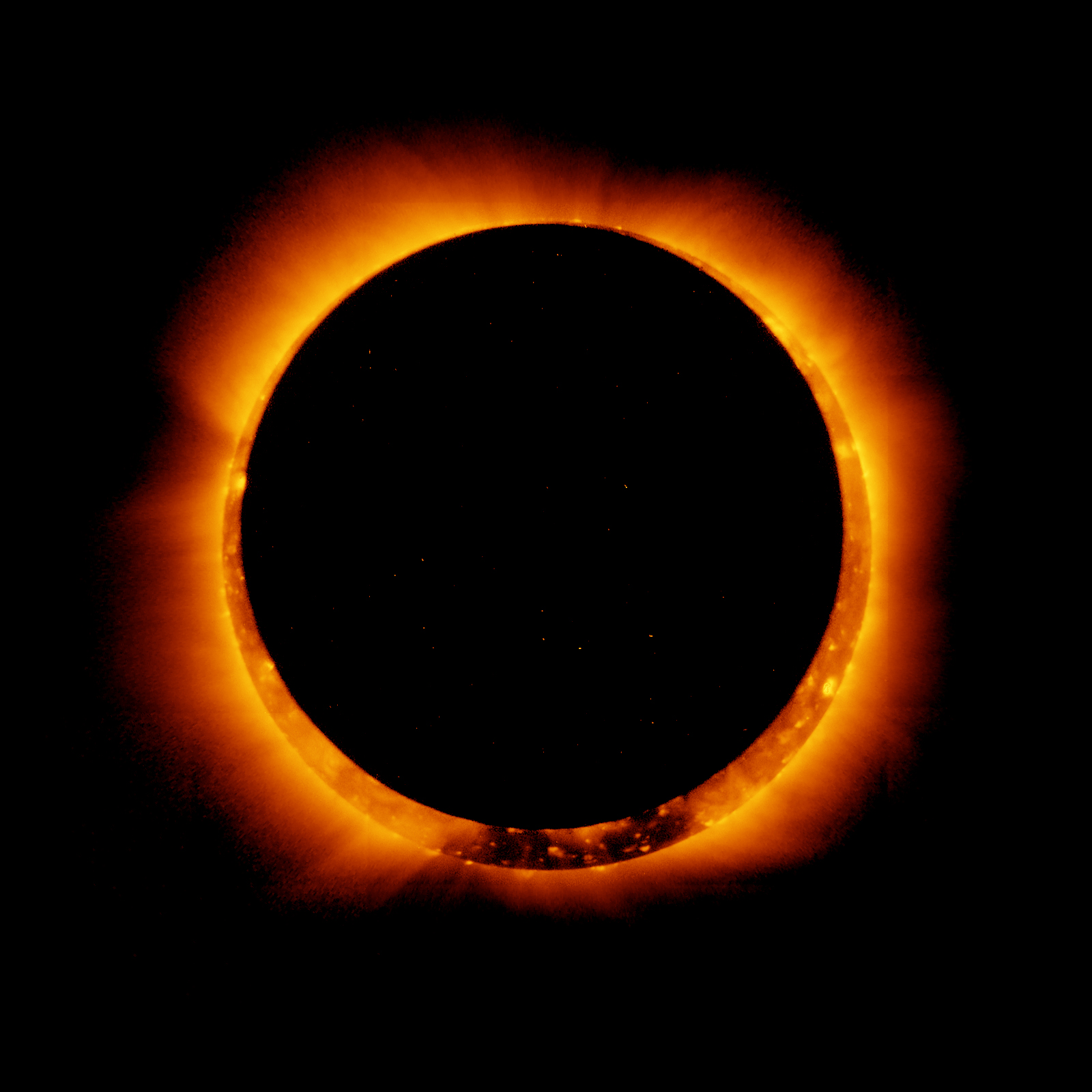

"The straw that broke the camel's back," Kentrianakis said, came during an expedition to Argentina in February, where he positioned himself outside what should have been the edge of an annular eclipse — where the moon is circled by a bright "ring of fire." A larger sun would make the "ring of fire" effect visible to a wider area.

"Technically, I should have been outside of annularity, [but the unfiltered photographs show] we were still in the path of annularity, and we have this beautiful chromosphere circling around at the edge," Kentrianakis said. That experience fully convinced him the sun was larger than generally thought.

This upcoming eclipse — which will very likely be the most-watched total solar eclipse in history, NASA officials have said — will provide a chance for others inside and outside the path of totality to help verify its size.

While researchers would ordinarily use the radius of the sun to compute exactly when the moon will cover and uncover the sun for a given location, called contact times, the opposite strategy is required here, Quaglia told Space.com. "If we can measure contact times accurately, everything else being the same, the only thing that can change is the solar radius. We can actually compute the solar radius that way," he said.

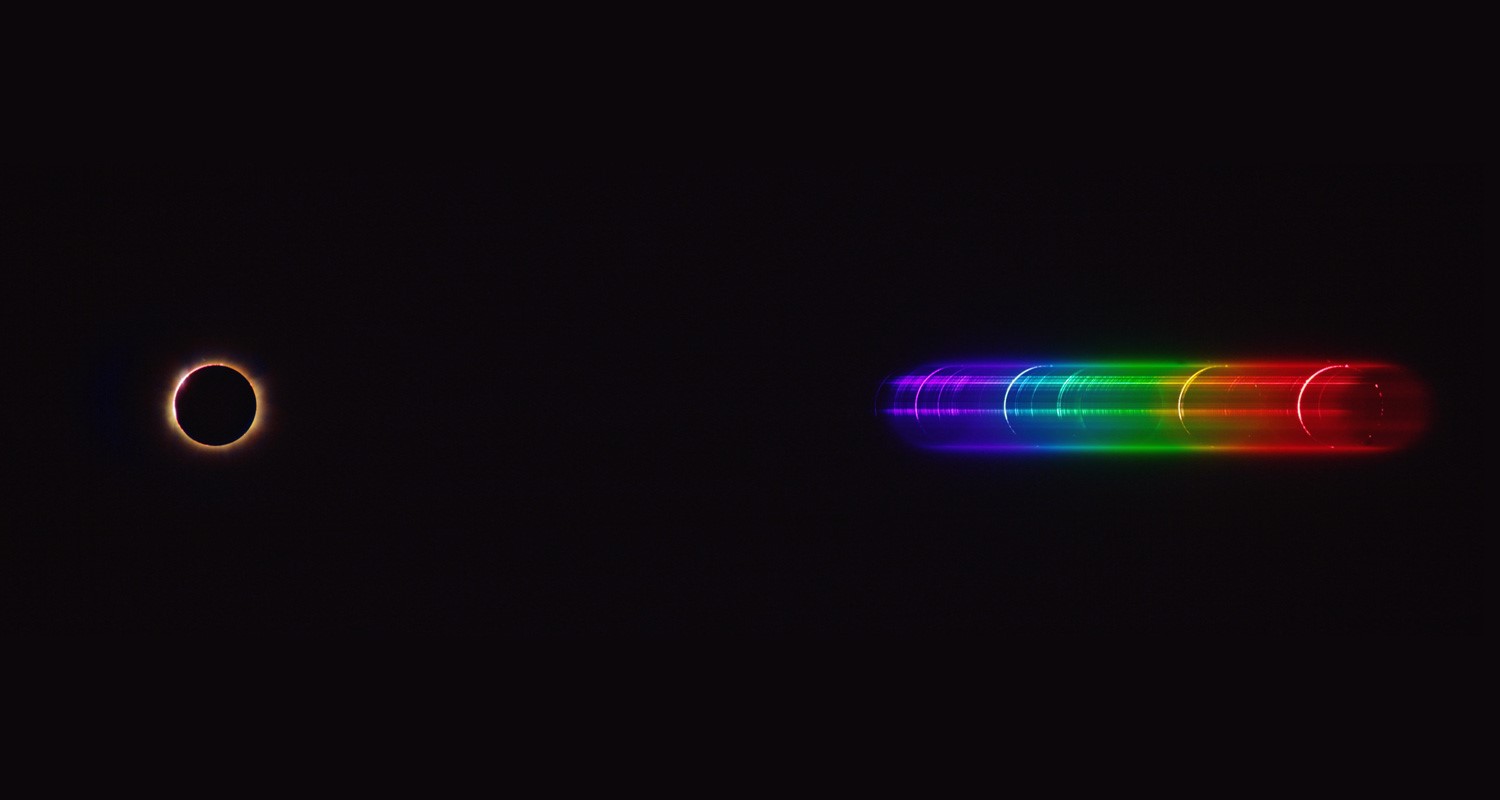

Kentrianakis, Jubier, Quaglia and others want to pin it down by positioning researchers inside and outside where totality should be, armed with the equipment for what's called a "flash spectrum" photograph. The process uses a textured grating over a camera, which splits incoming light into component wavelengths — making it easy to determine precisely when the entire photosphere has been covered by the moon, revealing a more limited set of wavelengths emitted by the chromosphere. Combined with accurate timestamps, that process would provide strong evidence for the sun's size. (Such a process has been used before, but on a limited scale, Quaglia said.)

Such measurements would also provide another benefit, Jubier said — investigating what some think is a thin layer in between the photosphere and chromosphere called the mesosphere. That thin layer can be visible for a moment after the photosphere is blotted out during an eclipse, which means observers may make measurements that confuse the mesosphere for more of the photosphere. A flash spectrum can help distinguish between the two, although it must be a high enough resolution so the signals from each can be clearly separated.

A group involving Quaglia, Kentrianakis and Jubier was unable to get funding for as broad a flash-spectrum experiment as they would have liked — something like 30 separate measurement stations arrayed just inside and just outside the predicted eclipse path. But researchers could still use crowdsourced data and measurements during the eclipse to learn more.

"The more observations we have the better even if they are not providing the kind of quality we expected to get from the cinematographic spectroscopy," Jubier said. "Time will tell what we can make of all this."

Jubier said that flash spectrum measurements would be most useful, but so would (safely!) unfiltered views of the eclipse. Most filters cut out details of the images, making it much more difficult to determine precisely when the sun fully covers the moon.

Other groups will also be using the eclipse to try and measure the sun's diameter, Quaglia said, including the International Occulting Timing Association, which will analyze smartphone videos taken at intervals perpendicular to the eclipse path in Nebraska.

"The more people, the more techniques, the more teams involved will get us there as a whole," Quaglia said. "If, then, the International Astronomical Union makes the decision to change the value, they will probably not change the value lightly."

Understanding the visible sun's exact size will be possible only by combining careful solar measurements with the simulations and precise understanding of the moon's and Earth's elevations that exist now, Jubier said. But the pieces are in place to make that determination, if enough people get on board to measure the most common sight in the sky during those uncommon moments of eclipse.

"It's big, and it will take many eclipses — it may take until 2024 — but at least we're starting it now," Kentrianakis said.

Editor's note: Space.com has teamed up with Simulation Curriculum to offer this awesome Eclipse Safari app to help you enjoy your eclipse experience. The free app is available for Apple and Android, and you can view it on the web.

This article was updated to clarify the resolution of Solar Dynamics Observatory images.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.