Hubble Telescope Detects Stratosphere on Huge Alien Planet

A huge, superhot alien planet has a stratrosphere, like Earth does, a new study suggests.

"This result is exciting because it shows that a common trait of most of the atmospheres in our solar system — a warm stratosphere — also can be found in exoplanet atmospheres," study co-author Mark Marley, of NASA's Ames Research Center in California's Silicon Valley, said in a statement.

"We can now compare processes in exoplanet atmospheres with the same processes that happen under different sets of conditions in our own solar system," Marley added. [Gallery: The Strangest Alien Planets]

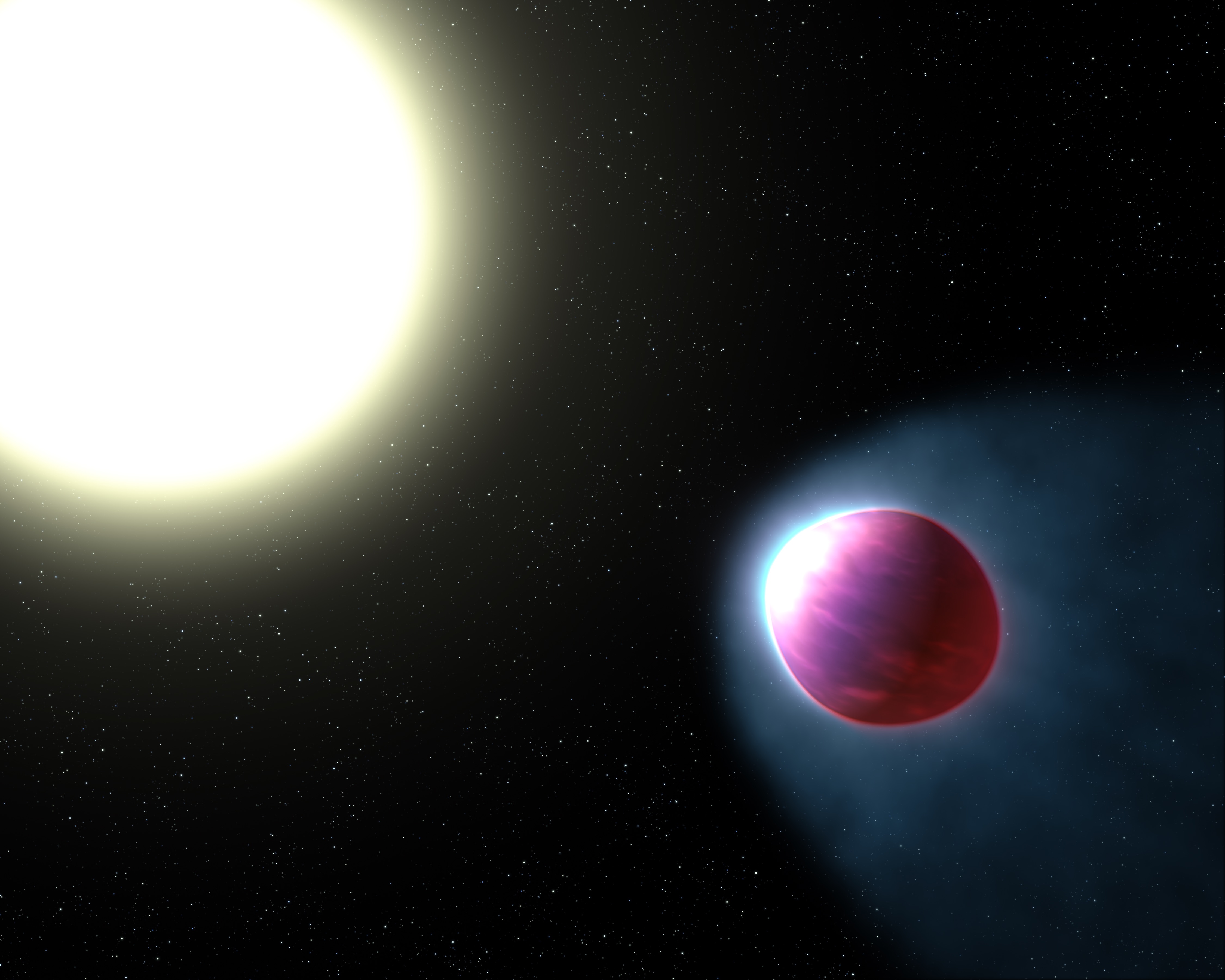

The research team, led by Thomas Evans of the University of Exeter in England, detected spectral signatures of water molecules in the atmosphere of WASP-121b, a gas giant that lies about 880 light-years from Earth. These signatures indicate that the temperature of the upper layer of the planet's atmosphere increases with the distance from the planet's surface. In the bottom layer of the atmosphere, the troposphere, the temperature decreases with altitude, study team members said.

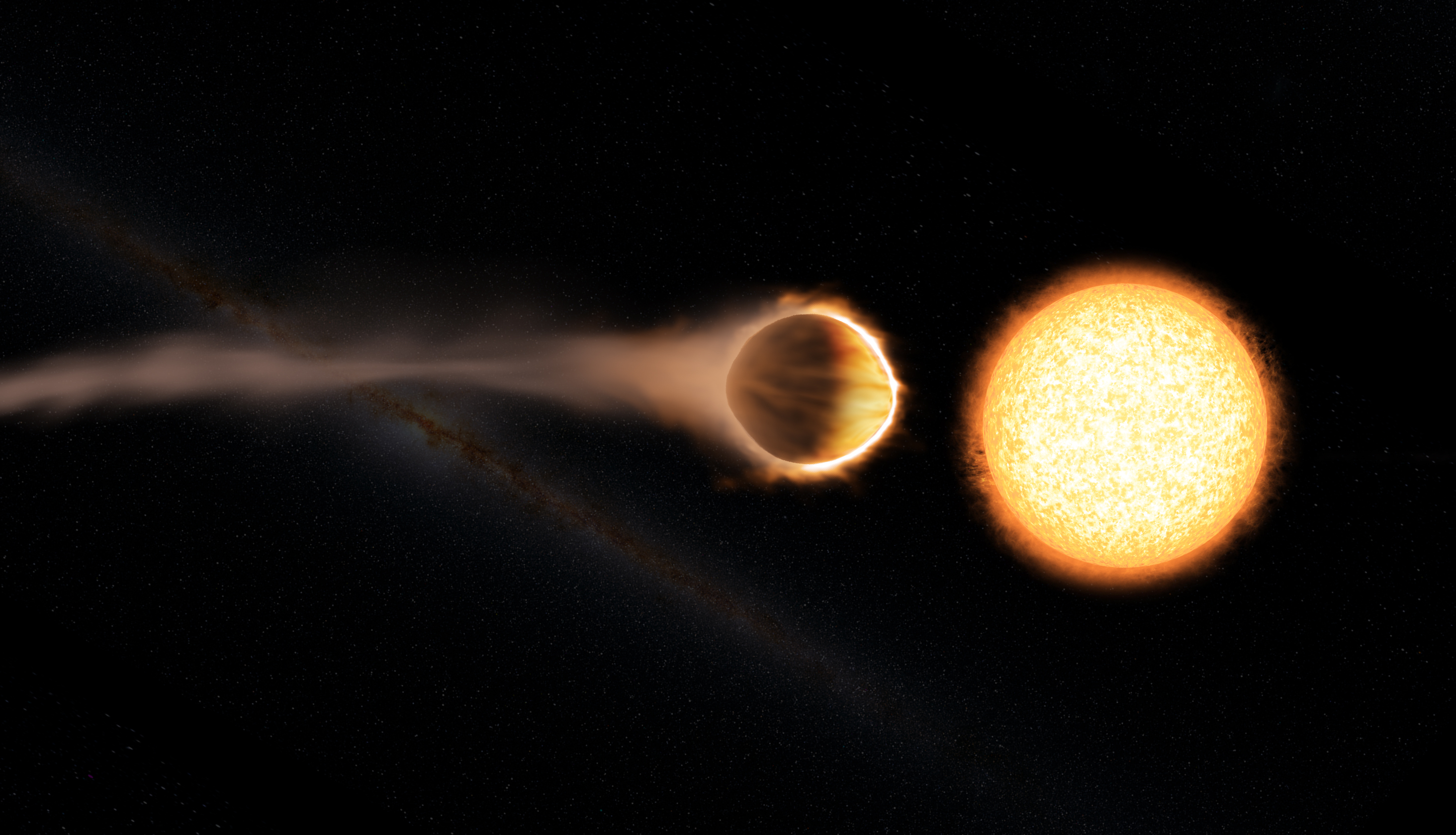

WASP-121b lies incredibly close to its host star, completing one orbit every 1.3 days. The planet is a "hot Jupiter"; temperatures at the top of its atmosphere reach a sizzling 4,500 degrees Fahrenheit (2,500 degrees Celsius), researchers said.

"The question [of] whether stratospheres do or do not form in hot Jupiters has been one of the major outstanding questions in exoplanet research since at least the early 2000s," Evans told Space.com. "Currently, our understanding of exoplanet atmospheres is pretty basic and limited. Every new piece of information that we are able to get represents a significant step forward."

The discovery is also significant because it shows that atmospheres of distant exoplanets can be analyzed in detail, said Kevin Heng of the University of Bern in Switzerland, who is not a member of the study team.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"This is an important technical milestone on the road to a final goal that we all agree on, and the goal is that, in the future, we can apply the very same techniques to study atmospheres of Earth-like exoplanets," Heng told Space.com. "We would like to measure transits of Earth-like planets. We would like to figure out what type of molecules are in the atmospheres, and after we do that, we would like to take the final very big step, which is to see whether these molecular signatures could indicate the presence of life."

Available technology does not yet allow such work with small, rocky exoplanets, researchers said.

"We are focusing on these big gas giants that are heated to very high temperatures due to the close proximity of their stars simply because they are the easiest to study with the current technology," Evans said. "We are just trying to understand as much about their fundamental properties as possible and refine our knowledge, and, hopefully in the decades to come, we can start pushing towards smaller and cooler planets."

WASP-121b is nearly twice the size of Jupiter. The exoplanet transits, or crosses the face of, its host star from Earth's perspective. Evans and his team were able to observe those transits using an infrared spectrograph aboard NASA's Hubble Space Telescope.

"By looking at the difference in the brightness of the system for when the planet was not behind the star and when it was behind the star, we were able to work out the brightness and the spectrum of the planet itself," Evans said. "We measured the spectrum of the planet using this method at a wavelength range which is very sensitive to the spectral signature of water molecules."

The team observed signatures of glowing water molecules, which indicated that WASP-121b's atmospheric temperatures increase with altitude, Evans said. If the temperature decreased with altitude, infrared radiation would at some point pass through a region of cooler water-gas, which would absorb the part of the spectrum responsible for the glowing effect, he explained.

There have been hints of stratospheres detected on other hot Jupiters, but the new results are the most convincing such evidence to date, Evans said.

"It's the first time that it has been done clearly for an exoplanet atmosphere, and that's why it's the strongest evidence to date for an exoplanet stratosphere," he said.

He added that researchers might be able to move closer to studying more Earth-like planets with the arrival of next-generation observatories such as NASA's James Webb Space Telescope and big ground-based observatories such as the Giant Magellan Telescope (GMT), the European Extremely Large Telescope (E-ELT) and the Thirty Meter Telescope (TMT). JWST is scheduled to launch late next year, and GMT, E-ELT and TMT are expected to come online in the early to mid-2020s.

The new study was published online Wednesday (Aug. 2) in the journal Nature.

Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. Originally from Prague, the Czech Republic, she spent the first seven years of her career working as a reporter, script-writer and presenter for various TV programmes of the Czech Public Service Television. She later took a career break to pursue further education and added a Master's in Science from the International Space University, France, to her Bachelor's in Journalism and Master's in Cultural Anthropology from Prague's Charles University. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.